After decades of its overuse in prisons and jails, the tide appears to be turning on restrictive housing. One of the most troubling practices in U.S. prisons and jails, it is generally defined as holding someone in a cell, typically for 22 to 24 hours a day, with minimal human interaction or sensory stimuli. In recent years, this practice has been the subject of increased scrutiny from researchers, advocates, policymakers, media, and corrections agencies.

A person is held in a cell for 22 to 24 hours a day, with minimal human interaction or sensory stimuli.

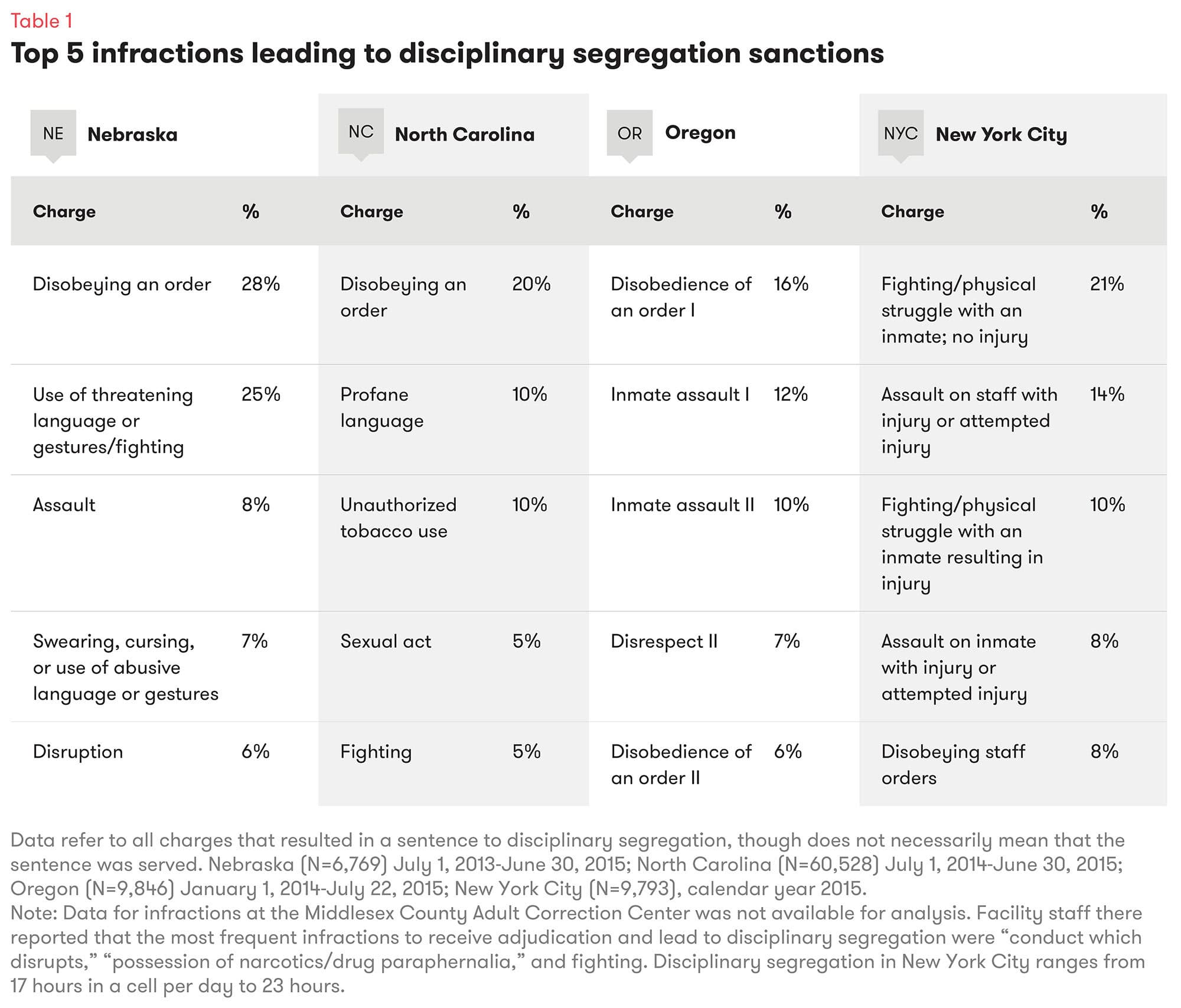

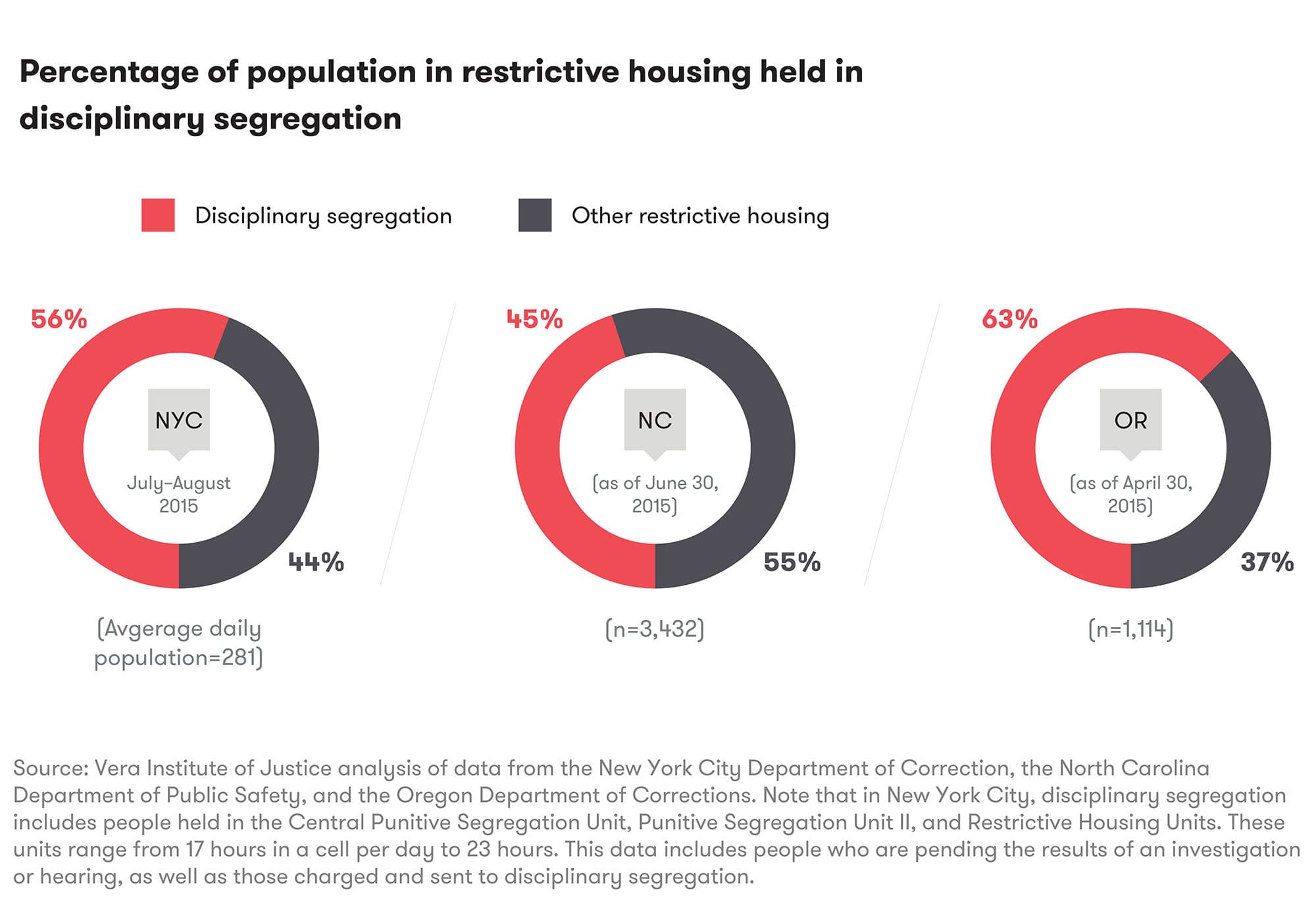

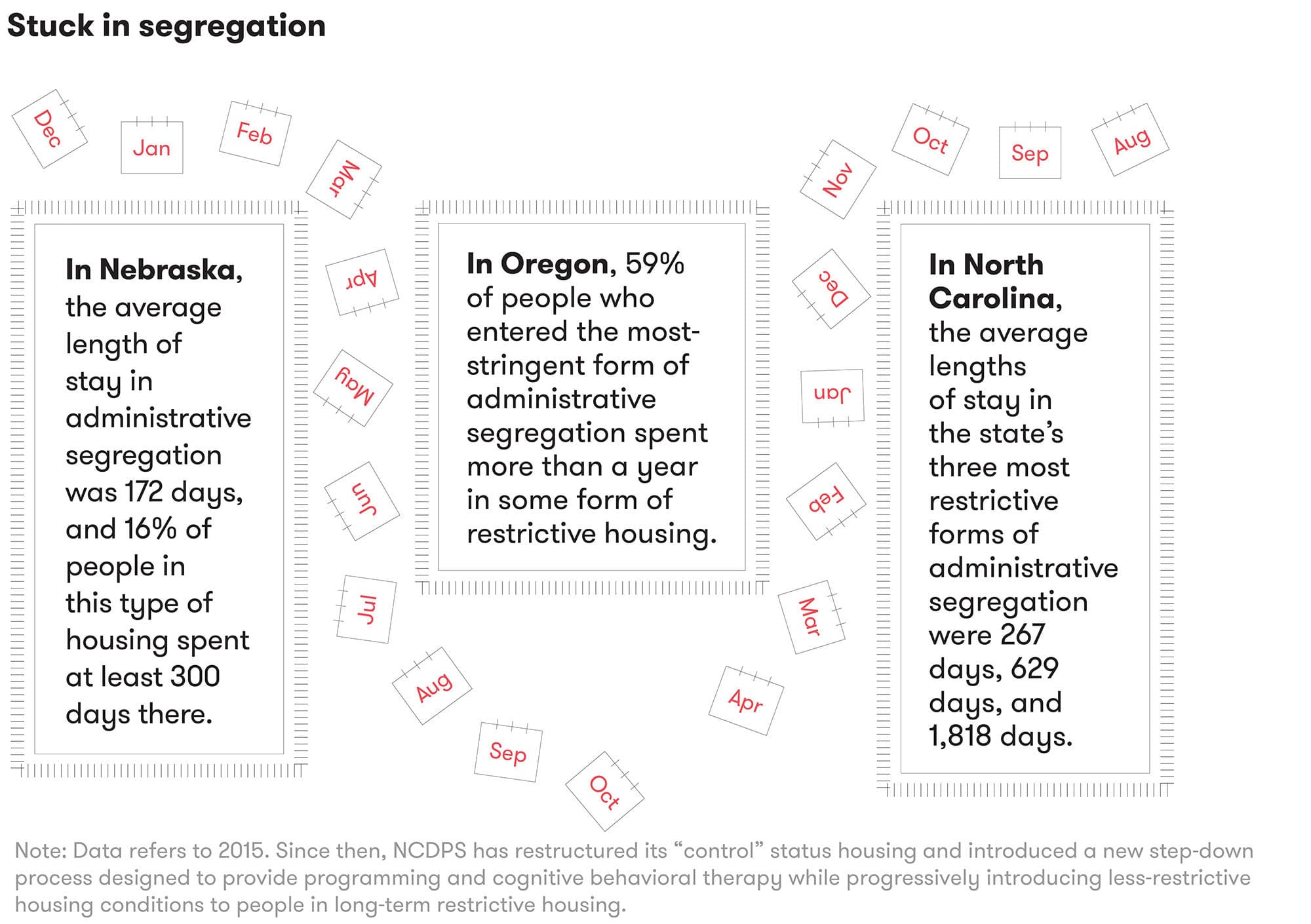

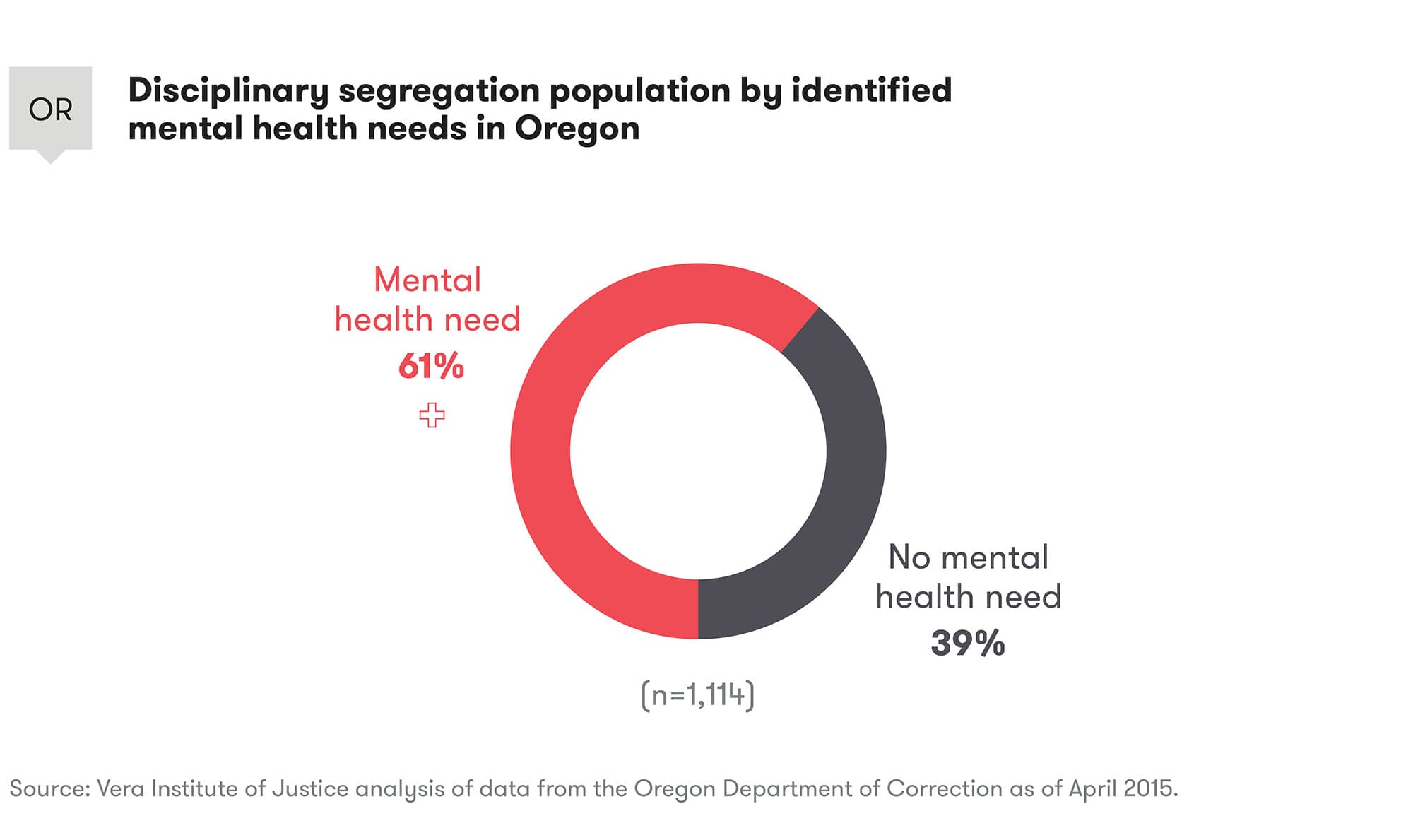

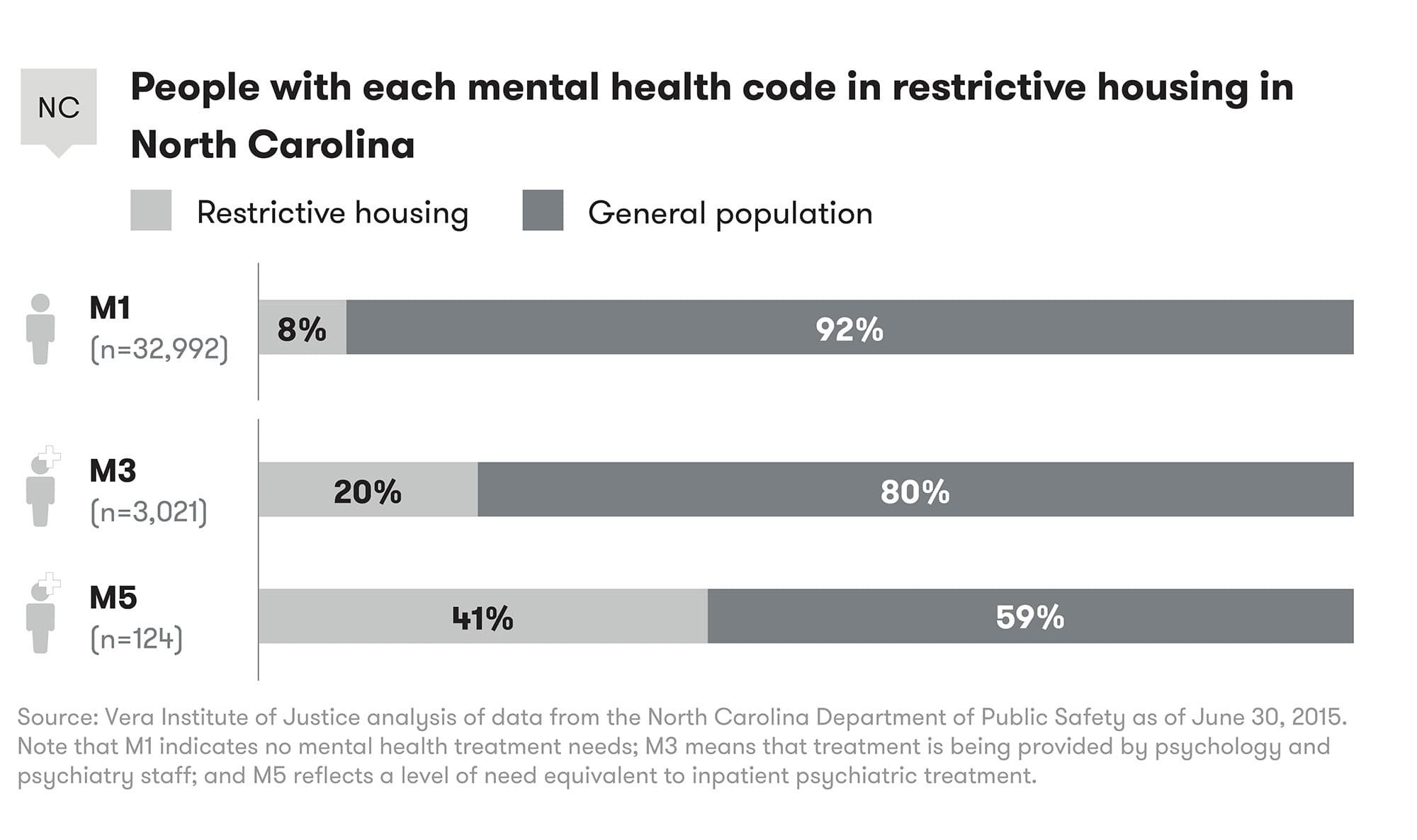

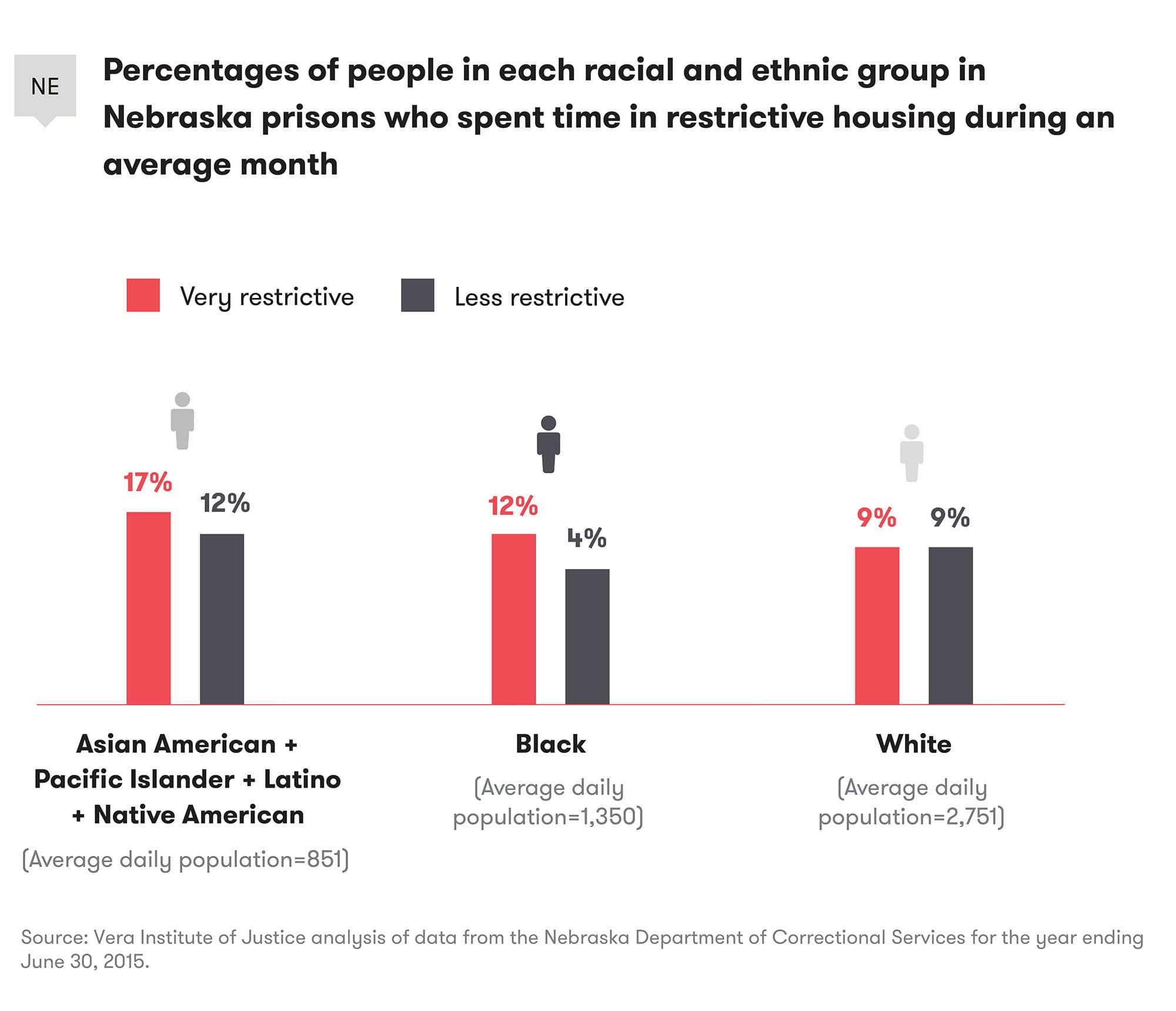

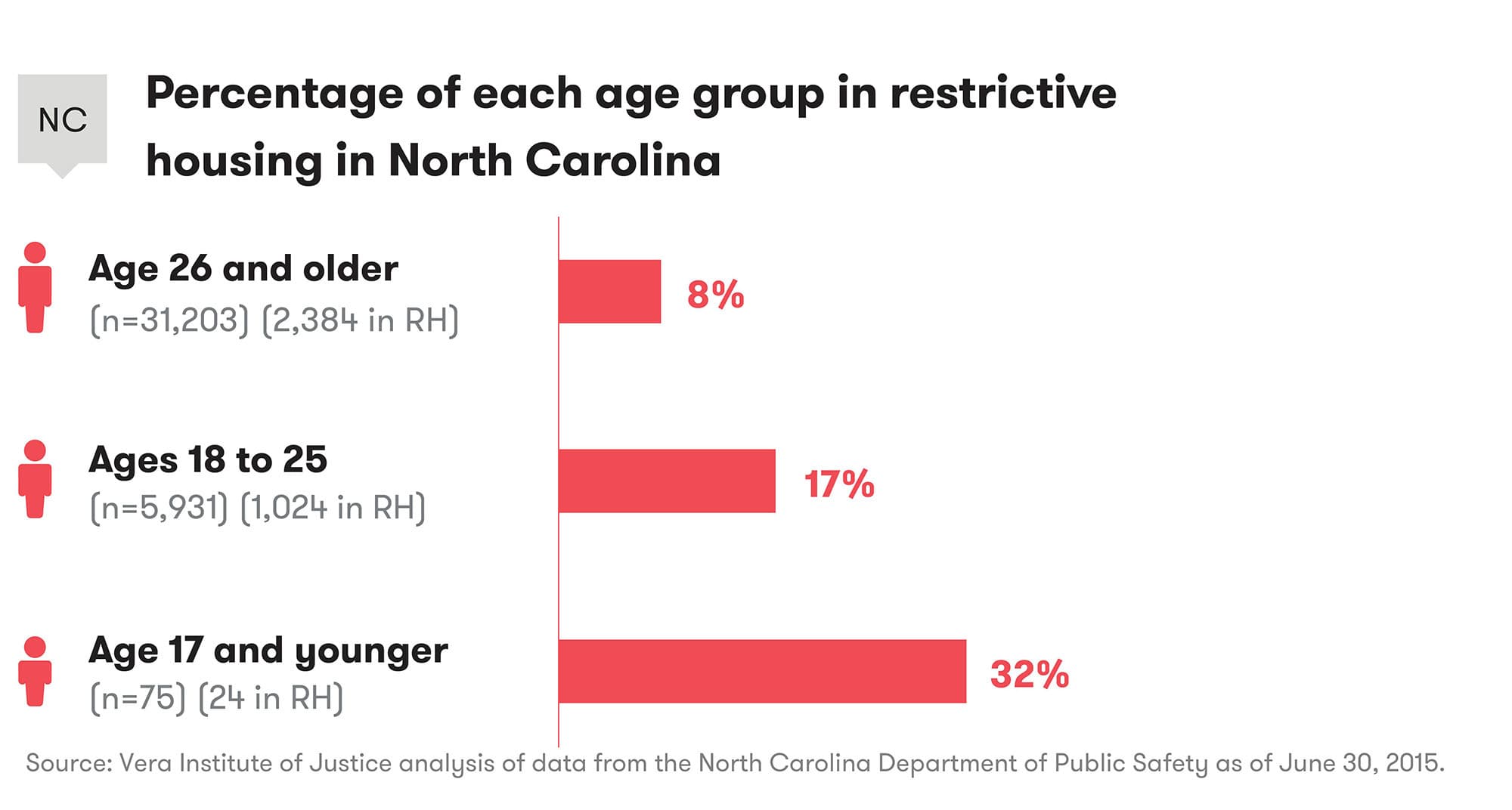

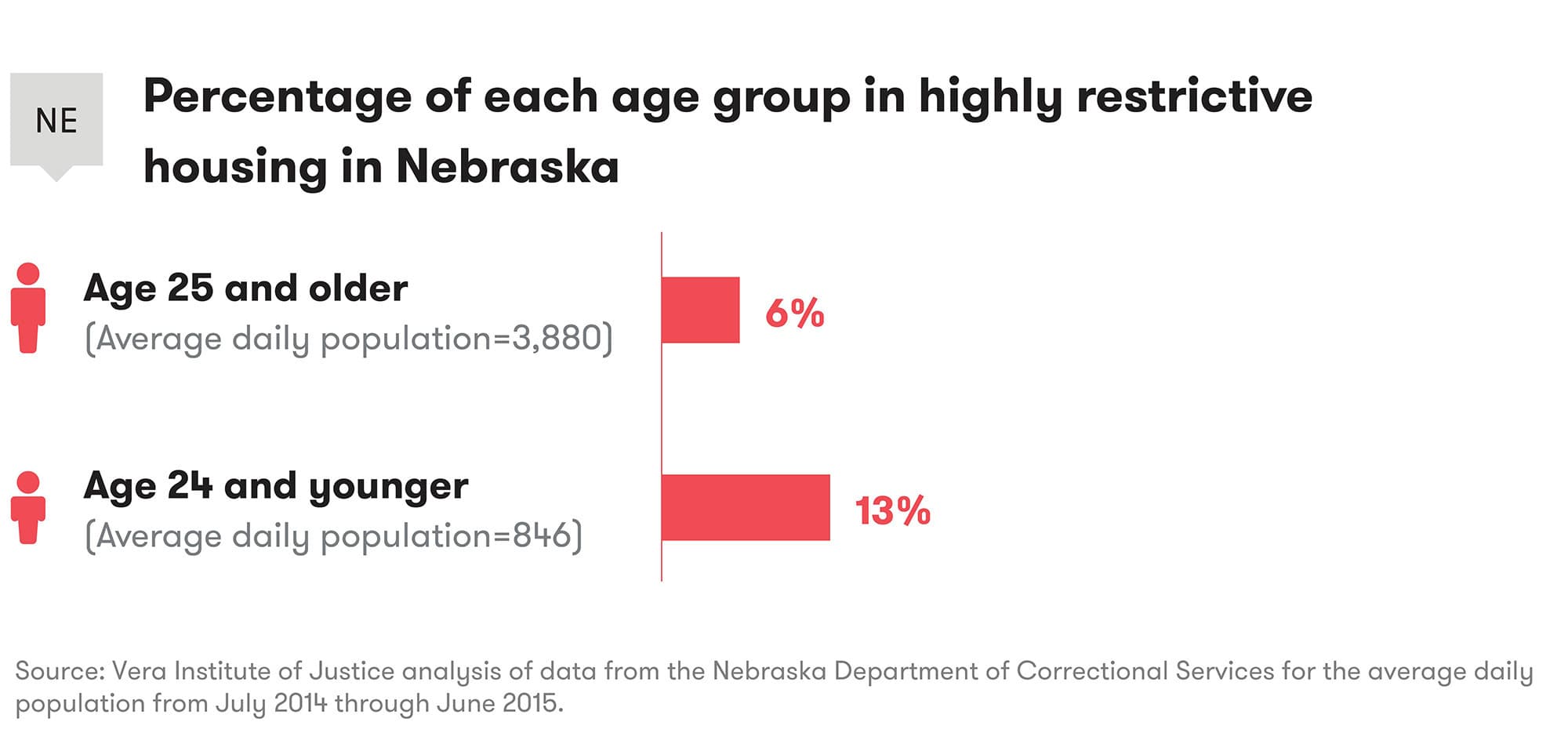

Since the 1980s, the increase in restrictive housing has mirrored the exponential rise of incarceration. Originally intended to manage people who committed violence within jails and prisons, restrictive housing has become a common tool for responding to all levels of rule violations, from minor to serious; managing challenging populations; and housing people considered vulnerable.[]Angela Browne, Alissa Cambier, and Suzanne Agha, “Prisons Within Prisons: The Use of Segregation in the United States,” Federal Sentencing Reporter 24, no. 1 (2011), 46–49. In short, just as systems have come to rely too heavily on incarceration, departments of corrections now rely too much on restrictive housing. And, as in other parts of the justice system, restrictive housing often affects disproportionate numbers of young people, people living with mental illness, and people of color.[]Association of State Correctional Administrators (ASCA) and The Arthur Liman Public Interest Program, Yale Law School, Time-In-Cell: The ASCA-Liman 2014 National Survey of Administrative Segregation in Prison (New Haven, CT: Yale Law School, 2015), 4; and Allen J. Beck, Use of Restrictive Housing in U.S. Prisons and Jails, 2011–2012 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2015, NCJ 249209).

But these problems can be solved. In light of growing evidence that restrictive housing may harm people without improving safety in facilities, a number of departments of corrections are taking steps to reduce their reliance on this type of housing.

See updates on reforms that five corrections departments have recently implemented and the effects these reforms are having on their use of restrictive housing.

Impacts of Restrictive Housing

Rethinking Restrictive Housing

-

In August 2016, the Standards Committee of the American Correctional Association—a professional association and accrediting organization for corrections—voted to pass comprehensive standards regulating the use of restrictive housing.

American Correctional Association, “Restrictive Housing Performance Based Standards” (2016)

-

In 2012, the Association of State Correctional Administrators (ASCA) teamed up with the Arthur Liman Public Interest Program at Yale Law School to survey directors of state and federal correctional systems on their policies regarding administrative segregation. The results of that survey were published in the report Administrative Segregation, Degrees of Isolation, and Incarceration: A National Overview of State and Federal Correctional Policies. The study was updated in 2015 with Time-in-Cell: The Liman-ASCA 2014 National Survey of Administrative Segregation in Prison and followed by a 2016 report, Aiming to Reduce Time-In-Cell: Reports from Correctional Systems on the Number of Prisoners in Restricted Housing and on the Potential of Policy Changes to Bring About Reforms. Additionally, in 2013, ASCA issued Restrictive Housing Status Policy Guidelines.

-

In April 2016, the National Commission on Correctional Health Care adopted a strong position statement calling for, among other things, the elimination of restrictive housing longer than 15 consecutive days and the exclusion of juveniles, pregnant women, and people with mental illness from restrictive housing.

National Commission on Correctional Health Care, “Position Statement: Solitary Confinement (Isolation)”

-

The U.S. Department of Justice published a comprehensive report in 2016 that called for far-reaching revisions to the Federal Bureau of Prisons’ restrictive housing practices. It also outlined a number of principles to guide state and local jurisdictions seeking to make similar changes.

U.S. Department of Justice, Report and Recommendations Concerning the Use of Restrictive Housing: Final Report (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2016).

-

The National Institute of Justice issued a 2016 report that questions whether restrictive housing achieves the intended goals of maintaining safety and order.

Natasha Frost and Carlos E. Monteiro, “Administrative Segregation in U.S. Prisons” (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, March 2016, NCJ 249749R.M), citing Ryan Labrecque, “The Effect of Solitary Confinement on Institutional Misconduct: A Longitudinal Evaluation” (PhD diss., University of Cincinnati, 2015), p. 23.

-

The United Nations General Assembly unanimously adopted the revised Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (known as “the Nelson Mandela Rules”) in 2015. The rules prohibit restrictive housing that is indefinite or prolonged (defined as the confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact for a period longer than 15 consecutive days). They also support restrictions on its use for juveniles, pregnant women, and people with disabilities or mental illness. Although not legally-binding, the Mandela Rules represent widely accepted international principles on the treatment of incarcerated people.

Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules), General Assembly Resolution 70/175, U.N. Doc. A/Res/70/175 (2015), Rules 43-45.

Against this backdrop, a growing number of corrections leaders want to change their systems’ approach to restrictive housing, in order to improve the safety and well-being of those who live and work in their facilities; make better use of resources; respond to interest from external stakeholders; and ultimately enhance public safety in the communities to which incarcerated people will return.[]See U.S. Department of Justice, 2016, pages 74-78, for descriptions of states and counties that have actively sought to reform their restrictive housing practices, including Colorado, Washington, New Mexico, Virginia, and Hampden County, Massachusetts; see also ASCA and the Liman Program, Time-In-Cell, 2015, 58. In a 2014 survey, administrators from 40 state corrections departments reported that they had recently reviewed their restrictive housing policies; by 2016, many of those jurisdictions had begun reforms to reduce their reliance on this practice.[]Association of State Correctional Administrators and the Arthur Liman Public Interest Program, Yale Law School, Aiming to Reduce Time-In-Cell: Reports from Correctional Systems on the Numbers of Prisoners in Restricted Housing and on the Potential of Policy Changes to Bring About Reforms (New Haven, CT: Yale Law School, 2016).

But the task is a challenging one. Jails and prisons are complex environments, and many forces are at play in changing their policies, practices, and cultures. Correctional staff have become so reliant on restrictive housing that in many jails and prisons it has become a part of everyday life and institutional culture; any attempts to reduce its use must therefore be carefully and strategically implemented. What’s more, to solve a problem one must first define and understand it—yet in many jurisdictions, antiquated records systems and lack of data make it difficult to assess how restrictive housing is being used.