Series: Target 2020

What Justice for George Floyd Looks Like

Justice for George Floyd—and countless other Black people who have been victims of police violence—requires more than Derek Chauvin’s conviction.

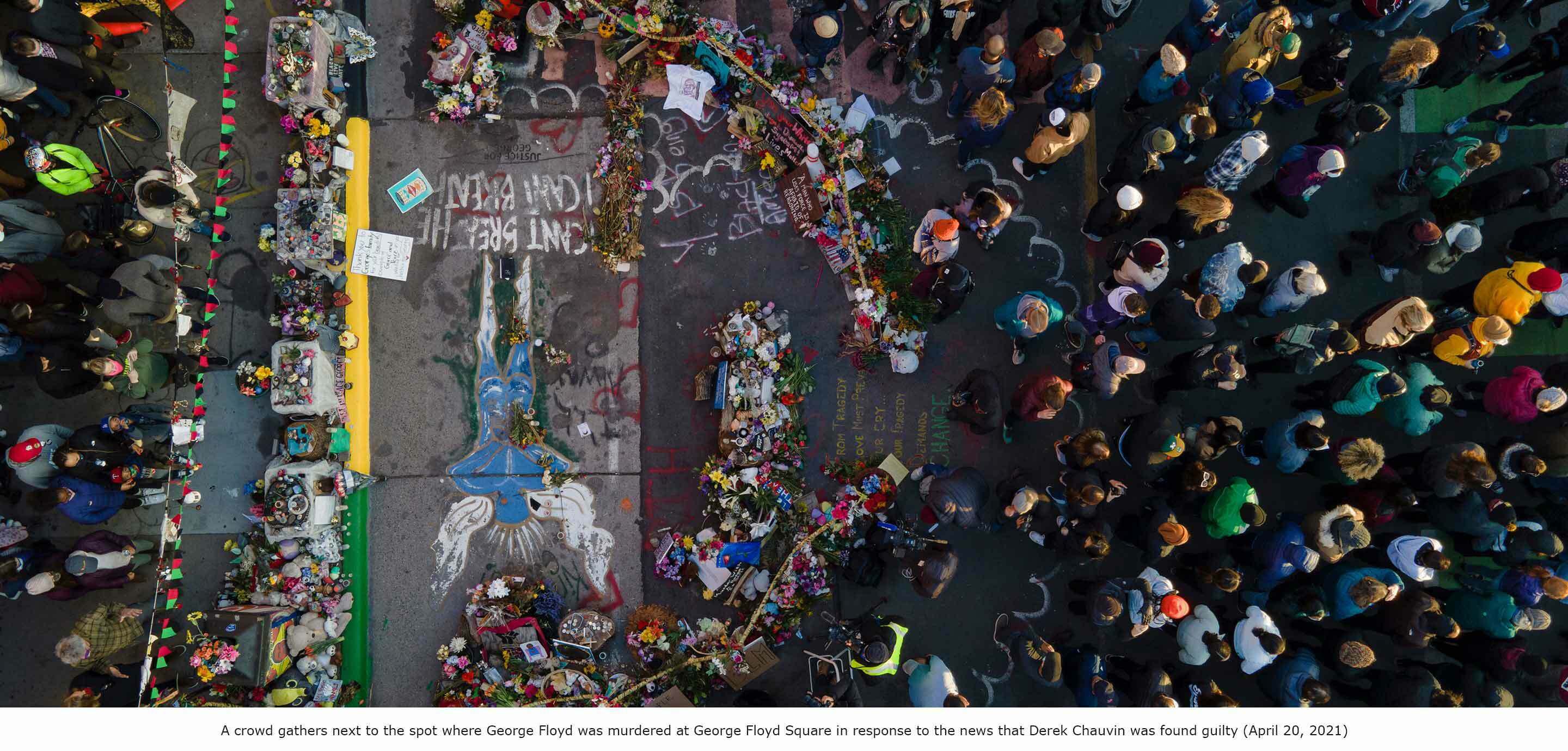

The audible exhalations and tears streaming down the faces of Black people—and our allies—after the news that Derek Chauvin was found guilty of murdering George Floyd represent relief that we achieved a rare thing: accountability. Many of us hadn’t allowed ourselves to believe or hope for it, but our relief is mixed with the bitter knowledge that this verdict will not stop the cycle of trauma and tragedy.

Two weeks into Derek Chauvin’s trial, Daunte Wright was killed by police officer Kimberly Ann Potter not far from the street where George Floyd was murdered last May. And on the same day the verdict was announced, Ma'Khia Bryant, a 16-year-old Black girl, was fatally shot by police in Columbus, Ohio.

Justice for George Floyd—and countless other Black people who have been victims of police violence—requires more than Chauvin’s conviction.

George Floyd’s murder inspired millions of people to protest across the country and around the world because it was so emblematic of the U.S. “justice” system’s brutality toward the descendants of people who were enslaved. This system was built at a time when Black people were not considered fully human under the law. And Chauvin’s comfort with casually suffocating a handcuffed Black man in front of other officers and a crowd of horrified witnesses—and the collective fear that he would be acquitted despite the overwhelming evidence—shows that this poisonous racism endures.

True justice for George Floyd means creating a system that provides real safety and security for everyone by building thriving communities that center individual well-being. Yet, the United States spends more time, energy, and money criminalizing, policing, and imprisoning people than helping them, with cities nationwide using about one-third of their general funds for law enforcement. We spend double on the apparatus of mass incarceration what we do on public assistance to poor, disabled, and low-income people. This imbalance must be corrected for our communities to thrive.

Black people bear the brunt of a system that prioritizes criminalization over communities at every level—from policing to prosecution to sentencing to incarceration. Police are far more likely to stop, search, and arrest people of color. Police are more likely to use force against Black people. Black people face tougher charges when arrested for the same crimes as white people. Black and Latinx people are punished with harsher sentences—including the application of the death penalty—than white people found guilty of the same crimes. Black people represent only 13 percent of the U.S. population, but 35 percent of incarcerated men and 44 percent of incarcerated women. Black people also make up the majority of those exonerated after wrongful convictions.

Overcriminalization too often means increased police encounters that result in death. At least 1,127 people were killed by police in 2020. Of those who were unarmed, most were people of color. And most of these deaths began with police responding to suspected minor, nonviolent offenses—like the alleged passing of a counterfeit $20 bill. An astounding 121 people were killed last year after police stopped them for suspected traffic violations.

Only 5 percent of the astronomical 10.5 million arrests made each year are for violent offenses. Eighty percent are for nonserious, low-level infractions that are often linked to homelessness, mental illness, substance use, or poverty—things that don’t require a police response.

Instead of continued overpolicing, communities need mental health care, substance use treatment, and a social safety network. We need fewer armed officers and more social workers, teachers, and mental health care providers to help people in crisis. Across the country, leaders are instituting alternatives to policing, including violence interrupter programs that dispatch trained, unarmed civilians. These kinds of efforts can produce a new kind of public safety—one that prevents crime instead of responding after the fact.

Derek Chauvin’s verdict will not return George Floyd to his children. It will not dissipate the rage and sorrow felt by families who mourn loved ones murdered at the hands of police and who know that no one will be held accountable for these deaths. To honor this pain, we must build a new framework for public safety and community well-being that respects and protects the humanity of all. Only then will there be justice for George Floyd.