To Ensure a Bright Future for LGBTQ Germans, Germany Acknowledges its Dark Past

Editor’s Note: This blog is part of our European Justice Models blog series, highlighting Vera’s trip to Germany and Norway to learn more about how other justice systems emphasize human dignity by improving conditions of confinement. These models have inspired Vera’s own Restoring Promise initiative, which works to transform conditions of confinement for young adults who are incarcerated. This piece focuses on LGBTQ issues with respect to the Holocaust, German commemoration, and continued overrepresentation of LGBTQ people in the US criminal justice system.

When he was 19, Sergei fled from his home country of Russia to France, and then went to Oxford University in Britain. It was at Oxford that Sergei fell in love with literature, and he followed that love back to Paris after completing his studies. There, he worked as a translator, and spent his evenings chatting, laughing, learning, and loving among the literary society that had made Paris its home in the interwar period.

He was, as best we can tell, happy. He lived as openly and honestly with respect to his sexuality—in early twentieth century Paris, no less—as many queer people do today.

But under the Third Reich, Sergei was arrested for homosexuality twice in Berlin—the first time, he served four months in prison. The second time, he was sent to Neuengamme concentration camp and forced to do hard labor.

He died there. He never returned to Paris, never read a novel again, never fell in love again, or had the opportunity to marry. His was a life cut short.

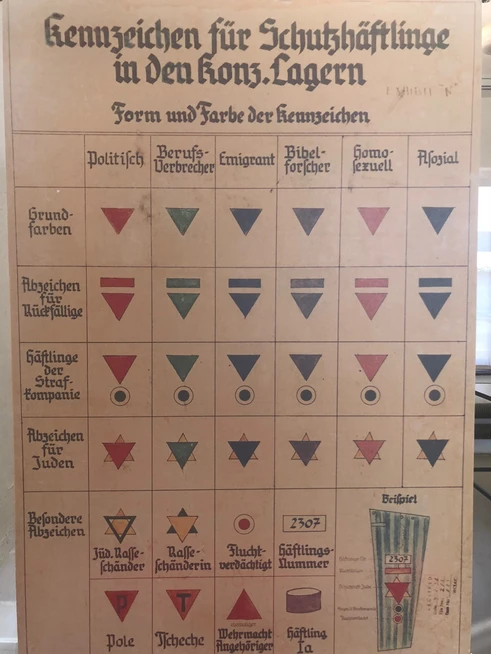

As part of our October trip to Germany and Norway to reimagine the American criminal justice system—and to understand the historical context that underscored Germany’s own reimagining of its prisons and justice system—our delegation of justice reformers and advocates visited Neuengamme, the concentration camp that Sergei was sent to. On that visit, we learned that Sergei was not alone. From 1933 to 1945, an estimated 100,000 men were arrested under the reign of the Third Reich for suspected homosexuality, approximately 50,000 of whom were officially sentenced (according to "Persecution of Homosexuals in the Third Reich", United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). Most of these men served time in regular prisons, and an estimated 5,000 to 15,000 of those sentenced were incarcerated in Nazi concentration camps. Some 60% of men held within the camps never made it out alive.

We also learned that the number of gender nonconforming people and women suspected of being homosexual who were arrested, sentenced, and killed is not known; there were no categories for sexuality outside of homosexuality in the Nazi sentencing, and so many would simply have been charged as ‘social deviants.’

In Berlin and Amsterdam, I went to visit the memorial sites commemorating the queer people who were persecuted and murdered simply for being who they were. I saw the power of acknowledging the past—and past atrocities—and using these commemoration sites as very visible reminders that what happened must never be allowed to happen again.

But I also learned that this commemoration was not instant, and, in fact, faced great resistance:

“After World War II, the treatment of homosexuals in concentration camps went unacknowledged by most countries, and some men were even re-arrested and imprisoned based on evidence found during the Nazi years. It was not until the 1980s that governments began to acknowledge this episode, and not until 2002 that the German government apologized to the gay community. In 2005, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the Holocaust which included the persecution of homosexuals.”

Despite the progress that has been made in the LGBTQ fight for equality across Europe and within the United States, we know that LGBTQ people continue to be overrepresented in the criminal justice system. In its report on how the criminal justice system fails LGTBTQ people, the Center for American Progress noted that data “shows [that] 7.9 percent of individuals in state and federal prisons identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, as did 7.1 percent of individuals in city and county jails. This is approximately double the percentage of all American adults who identify as LGBT, according to Gallup (3.8 percent).” What’s more, 16 percent of trans and gender non-conforming respondents in a survey indicated they’d spent time in jail or prison, compared to 5 percent of the general population.

We also know that queer individuals are especially vulnerable to hate crimes, targeting by law enforcement, mental illness, substance use disorders, and lack of access to health care—but this is especially true for queer people of color. When it comes to believing the justice system will treat them fairly, queer people of color report the lowest levels of confidence among all groups surveyed. As Vera’s Izzy Sederbaum put it in an interview last year, “We know that queer folks of color [and] transgender women of color, they get the short end of the stick. They have a system that is meant to be violent and penal to keep people of color, basically, and then you have this inherent violence toward queer people.”

Germany’s acknowledgement of its dark past—and the direct steps taken to rectify past wrongs—is one step in paving the way towards a brighter future. It is an example that America should follow, both for its LGBTQ people, people of color, and all other marginalized groups.

As the United States continues to grapple with its own legacy of racial terror, oppression, white supremacy, and anti-Semitism, these memorials—and the actions taken beyond their symbolism—show us the importance of facing those truths openly and honestly in an attempt to heal.

But acknowledgement is not enough. At a time in which anti-Semitism in Europe is rising—and becoming more publicly-visible—and Pittsburgh, PA is still reeling from a mass shooting at a synagogue, amidst other hate crimes, threats, and acts of violence across the country, it is clear that there remains much to be done in order to ensure that acknowledgement of past wrongs is accompanied by actions to help prevent future wrongs.