This Teacher Says Incarcerated People Are “The Best Students You’ll Ever Encounter”

Thomas Anderson remembers when Coppin State University (CSU) began offering college courses to people in Jessup Correctional Institution (JCI) in Maryland: sometime in 1999. Access was limited, however, and only about 20 students out of a population of more than 1,700 were able to complete a certificate for 30 credits. The CSU program ended in 2001, and JCI became an academic desert for 11 years.

So in 2015, when Andrea Cantora saw the announcement of the U.S. Department of Education’s (ED’s) Second Chance Pell Grant Experimental Sites Initiative (SCP), which provides need-based Pell Grants to people in state and federal prisons, she eagerly brought the idea to the attention of her colleagues at the University of Baltimore (UBalt). Cantora has worked on criminal legal system reform issues and volunteered at juvenile and mental health facilities since she was an undergrad. She also had opportunities to visit the Federal Correctional Institution in Danbury, Connecticut, where she was impressed by the variety of educational programming available for incarcerated people and wondered why these kinds of classes weren’t available more widely.

After working as a reentry coordinator in the Bronx, teaching college classes at Jessup Correctional Institution in Maryland, and bringing on-campus students to prison via the Inside Out Prison Exchange Program, Cantora knew that SCP would fit perfectly with UBalt’s mission and traditions, including engaging the Baltimore community, accepting nontraditional students, and providing opportunities for people with low incomes.

“Everyone was immediately excited about it,” Cantora remembers when she told UBalt faculty and staff about the opportunity to become an SCP site.

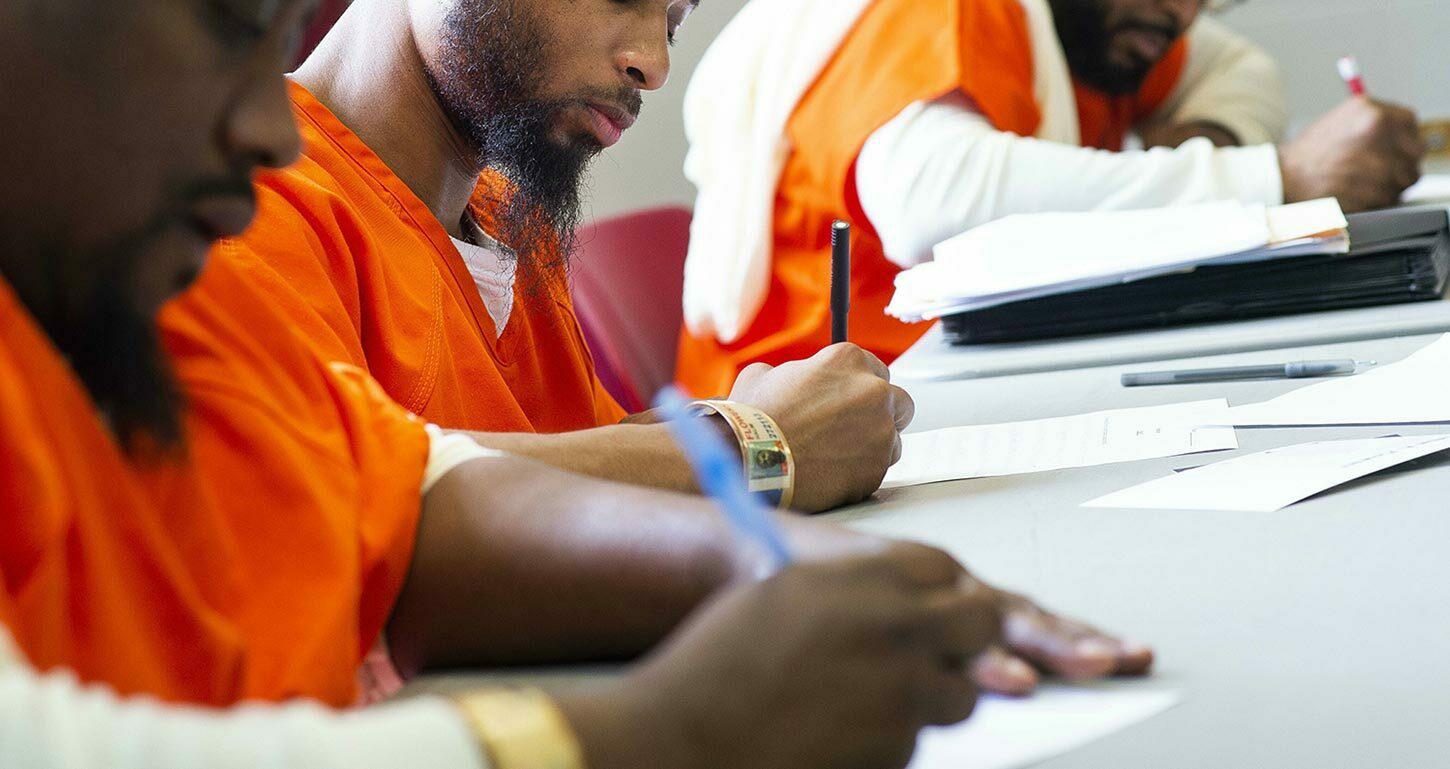

In June 2016, UBalt was accepted into SCP’s first cohort, and Cantora was named director. Through the pilot program, the school began offering a bachelor’s degree program with federal Pell Grant funding, and Anderson began taking general studies and human services courses through UBalt’s curriculum in 2017. As of the spring 2021 semester, UBalt’s Second Chance College Program had 48 students working toward a bachelor of arts degree in human services administration. The program is expecting to celebrate its first graduation this fall, and Anderson anticipates graduating with a bachelor’s degree in business administration with concentrations in real estate and economic development in the fall of 2022.

Although SCP allows thousands of incarcerated students access to college courses that they otherwise couldn’t, access to Pell Grants for everyone in prison was banned by the federal government in 1994. That changed last December, when Congress voted to lift the ban. Today, while ED works to make access to Pell Grants a reality for all people in prison, it recently announced an expansion of SCP from 130 colleges in 42 states to up to 200 colleges in all 50 states.

Josh Miller, Cantora’s colleague and co-founder of the Prison Scholars Program at Jessup Correctional Institution, also advocated for college in prison programming at the universities where he’s worked, including Penn State and Georgetown.

“Georgetown is committed to the idea that our graduates will become leaders, and we expect the same from students who are incarcerated: we look to them as leaders of working to end mass incarceration,” says Miller. “As a Jesuit university, Georgetown’s Prison and Justice Initiative offers an opportunity for students and faculty to live out our mission of committing to educate the whole person. We are also always striving to make sure our student body includes people with diverse life experiences.”

But many incarcerated applicants have been stymied by questions on FAFSA forms about Selective Service registration and drug convictions. “I saw many times how those lines on the form could fully put an end to someone’s plans to enroll, and it was incredibly frustrating,” says Miller. Fortunately, in July, ED announced that incarcerated Pell applicants could ignore these questions. For colleges that are planning a new program in prison, Vera has provided a useful report that can help guide their efforts.

Cantora and Miller acknowledge that starting up a program for incarcerated students is a significant challenge but say that as long as a university is willing to allocate time, faculty, and resources, it can be immensely rewarding. One of Miller’s mentors who teaches at the Bard Prison Initiative, Daniel Berthold, says that working with incarcerated people gives you “an opportunity to teach the best students you'll ever encounter.”

As for Anderson, he has seen firsthand how opportunities to take college courses lowers a person’s chances of returning to prison. “Prison is like a maze,” he says. “All kinds of things lurk around its corners. Externally there is violence, gangs, drugs, alcohol, and abusive authorities. Internally there’s feelings of fear, depression, loneliness, and doubt. All these things try to block you and confuse you at every turn. Education provided me with a roadmap and navigational system needed to overcome the maze. Now I stand as a free man on the other side.”

Miller says that as college in prison programs partner with more departments of corrections and more people understand their positive impact, he is hopeful that one day incarcerated applicants will be able to choose the educational experiences they want and won’t have to just accept what is offered. As Vera has learned, expanding high-quality postsecondary education in prison is a proven strategy that helps to address racial equity, improves safety, and expands opportunity in our country. Everyone deserves a chance.

Interested schools must submit an initial letter of interest by October 28, 2021.