The Road to Freedom for Cyntoia Brown Was Much Longer Than 15 Years

This Women’s History Month, we will be spotlighting key efforts and achievements in the movement to advance equal justice for women and girls nationwide.

I recently had the opportunity to visit the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama with board members and staff of the Vera Institute as part of our ongoing effort to address racial equity as an organization.

The museum displays historical records stretching from the transatlantic slave trade to the rise of mass incarceration, challenging visitors to grapple with deep connections between the past and present.

One of the museum’s displays features the story of a girl named Celia. According to historical records of Celia’s testimony and court documents, at the age of 14, she was sold as a slave to a white man named Robert Newsom who subjected her to repeated rape over a period of years. Evidence indicates this was the routine experience of enslaved people, particularly enslaved women and girls. Celia warned Robert Newsom that she would hurt him if he continued to rape her. When he attempted to rape her again, she killed him. In the court proceedings that followed—State of Missouri vs. Celia, a Slave—the judge refused to allow consideration of self-defense in the jury instruction, and Celia was convicted of murder by a jury of 12 white men. On December 21, 1855, Celia was hung for the killing in Fulton, Missouri.

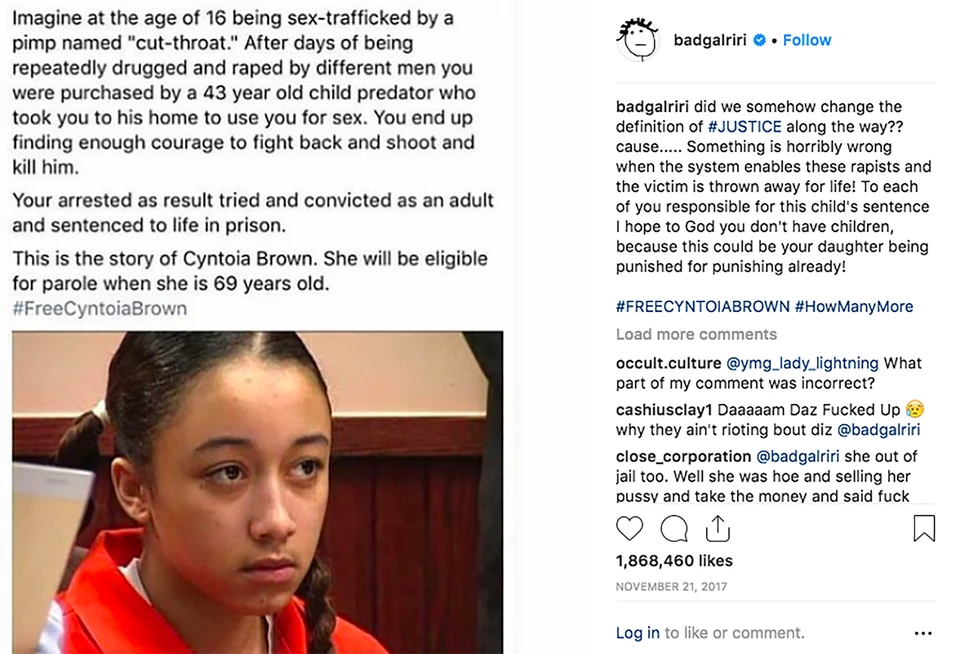

The morning of our visit to the museum—January 7, 2019—was the morning that then-Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam announced he was granting clemency to Cyntoia Brown. As I read about Celia’s story, the connections to Cyntoia’s case were clear. In 2004, at the age of 16, Cyntoia Brown had been forced into prostitution by a pimp who controlled her by beating her, raping her, and pointing guns at her as he repeatedly sold her body to turn a profit, making her a victim of sex trafficking according to current federal law. She feared harm to herself or harm to her family if she did not comply with her pimp’s demands. One night, a 43-year-old white man paid $150 to buy her for sex. According to Cyntoia’s testimony, the man was showing off the guns in his home and she became fearful that he would rape or kill her. At one point, when Cyntoia thought the man was reaching for one of his guns to hurt her, she grabbed a gun and killed him.

It is an injustice to Cyntoia to view her story absent an analysis of race. Today, structural racism that sustains higher rates of poverty in black communities and communities of color systematically makes black girls more vulnerable to trafficking, juvenile justice involvement, and a host of other harms. According to a two-year review of all suspected human trafficking cases nationwide published by the Bureau of Justice statistics, 94 percent of sex trafficking victims were women and girls and 40 percent of confirmed sex trafficking victims were black, although women are half of the US population and black people are 13 percent of the US population overall.

Available evidence shows that while victims are disproportionately black and are disproportionately girls, buyers are often white and middle-to-upper class. For example, in King County, Washington, 44 percent of all child sex trafficking victims are black, though black people only comprise 7 percent of the general population in the county. Meanwhile, 80 percent of identified sex buyers of children in the county are white men.

Cyntoia’s case represents an extreme example of what my co-authors and I called the “sexual abuse to prison pipeline” in a report published in 2015. The report documents the pathway girls often take from being a victim of sexual abuse or sex trafficking to later being involved in the juvenile justice system, where as many as 80 percent of girls are victims of sexual abuse. Girls are usually criminalized for minor misconduct related to their abuse and, frequently, for the steps they took to protect themselves from abuse and violence, including fighting back when they are attacked, running away, and struggling to survive on the streets. Landing in the juvenile justice system because of efforts taken to resist sexual abuse and other forms of violence is a harm that disproportionately impacts girls of color, particularly black, Native American, and Latinx girls who are overrepresented in the juvenile justice system.

Bias against black girls today influences the treatment of girls like Cyntoia in schools, child welfare systems, emergency rooms, and police stations, informing whether girls like Cyntoia are able to access help when they are harmed. In a recent study, Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood, published by the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, researchers found that adults viewed black girls as young as five years old as in need of less nurturing, in need of less protection, as being more independent, and more knowledgeable about adult topics, including sex, than white girls. Research concluded that common stereotypes undergird bias against black girls. These stereotypes—notably the stereotype of the jezebel—are rooted in slave era portrayals of Black women that justified systemic rape by slave owners through hypersexualization and dehumanization, painting black women and girls as so morally lascivious that they were unable to be raped.

Despite the circumstances in which the killing occurred, Cyntoia was not shown any leniency in the court proceedings that followed: she was tried in the adult court system in Tennessee, convicted of 1st degree murder, and given a life sentence without eligibility for parole until she had served 51 years in prison. In the years following Cyntoia’s sentencing, advocates and lawyers rallied around her. The case eventually grabbed the attention of celebrities like Rihanna and Kim Kardashian, who both called for Cyntoia to be released. It was in the midst of sustained organizing from advocates in Tennessee and attention from national press that Cyntoia was granted clemency, which has been framed in the press as a significant victory in contemporary context both for humane sentencing of juveniles and a promise of turning tides in the justice system for victims of sex trafficking.

Needless to say, it has been a long road to justice for Cyntoia, who will have served 15 years—nearly half of her life—in prison when she is released later this year. But the demand for justice that led to her release has gone on much longer. As we look towards the impact of Cyntoia’s release on the future, we would be remiss without stopping to note how Cyntoia’s life, and the lives of many girls like her, are informed by our past. We have come a long way from days when Celia was not recognized as a person under the law who had any right or standing to claim self-defense, but we have made decisively insufficient progress in recognizing the full humanity of black girls, realizing their right to safety, and affording black victims of sexual violence justice and the full protection of the law. Actor and Activist Alyssa Milano’s poignant op-ed discussing the importance of Cyntoia’s story in shaping the agenda of the #Metoo movement is a prescient analysis of the work left to be done.