The Prosecutors Refusing to Criminalize Abortion

Vera talked to prosecutors in Georgia, Illinois, and Texas about how abortion criminalization laws target their communities, and why they refuse to enforce them.

Following the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, roughly half of all states have or are expected to soon enact bans on abortion. These laws could lead to criminal charges against people seeking abortion care, reproductive care providers, and those who facilitate abortion services.

Although conservative state legislatures have already begun to criminalize abortion, enforcement of these laws will depend on choices by law enforcement and, critically, by prosecutors like district and state’s attorneys. Most prosecutors are elected directly by the jurisdictions they serve and have an enormous amount of discretion when it comes to what offenses they charge people for and what sentences they pursue. And across the country, electorates support legal abortion by an overwhelming margin—even in traditionally conservative jurisdictions.

Some prosecutors use discretion to refuse to prosecute in instances that could exacerbate the harm already caused by the criminal legal system. For instance, a district attorney can choose not to prosecute crimes of poverty and homelessness, like public camping or loitering, that would jail people for not having money. They can also decline to bring charges, like those coming from non–public safety traffic stops, that would compound racial injustice in their community while not improving public safety. Historically, reform prosecutors have used this power to decline to charge people under laws that target marginalized groups, like people of color and LGBTQ+ people. These decisions send a message to law enforcement not to waste resources investigating and policing already overpoliced communities under unjust policies.

Immediately following the Dobbs ruling, 84 district attorneys and other prosecutors from 29 states and territories and the District of Columbia sent precisely that message. They pledged not to press charges against people seeking abortion care or their providers, citing the potential harm to people who are “often the most vulnerable and least empowered” (in the United States, 62 percent of those who seek abortion services are people of color and three quarters have low income). This refusal to prosecute carries radically different implications in different jurisdictions. In Florida, for instance, Governor Ron DeSantis suspended Andrew Warren, the elected state attorney for Hillsborough County, because Warren refused to prosecute the state's abortion ban.

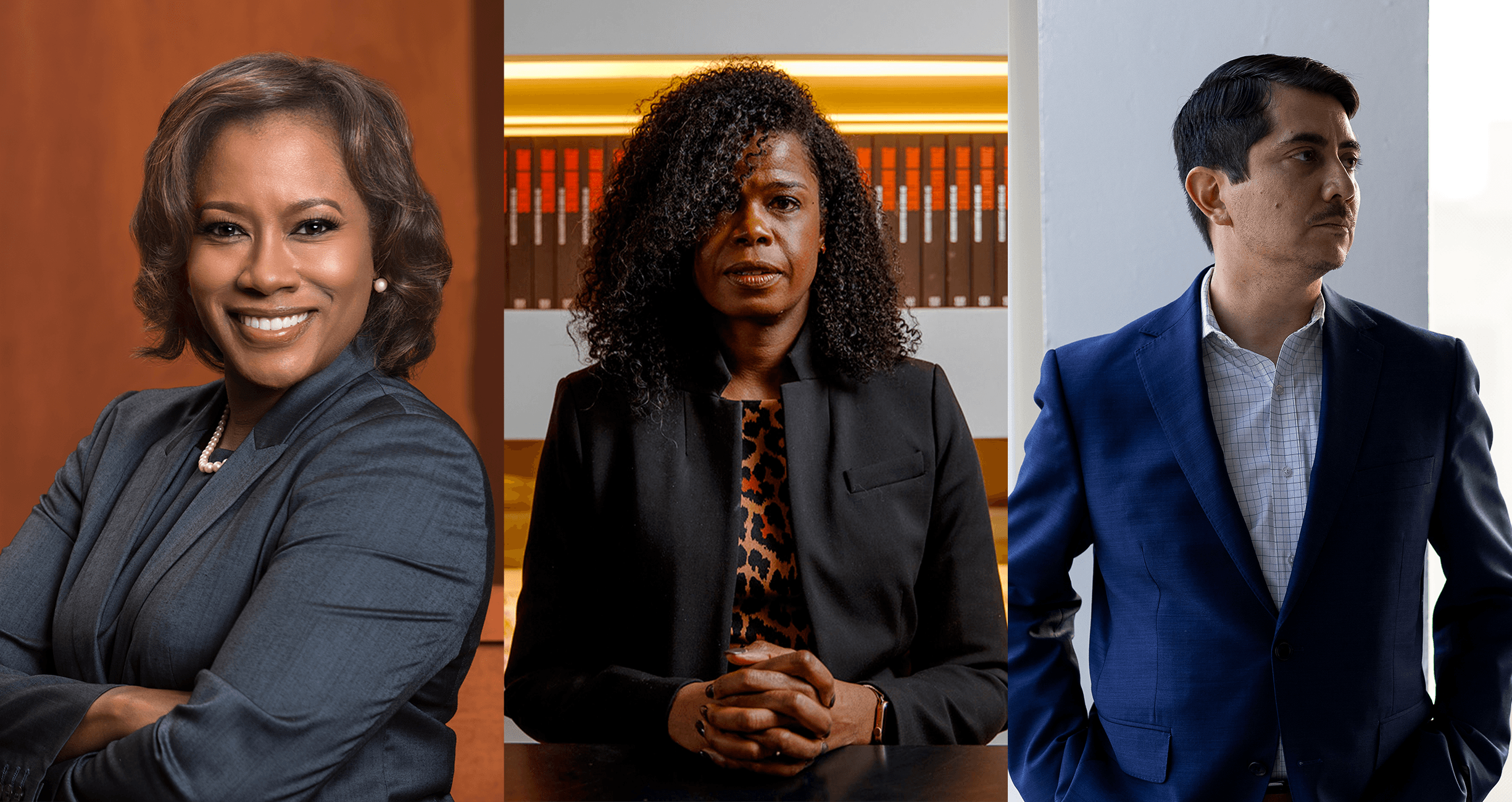

Vera spoke to three of the letter’s signatories in very different political contexts—one from Georgia, one from Illinois, and one from Texas—about how they intend to protect abortion access, why justice depends on exercising discretion in these cases, and what political challenges they face.

“How many of us will stand up and fight?” Dekalb County’s Sherry Boston on the racial intersections of abortion criminalization

In Georgia’s DeKalb County (a part of the Atlanta metro area), District Attorney Sherry Boston enjoys something of a mandate: she won an uncontested second term in 2020 and has been in office since 2017. DeKalb County is 55 percent Black, and Boston, a Black woman, is acutely aware of how abortion criminalization carries a serious threat to her community.

“When abortion was illegal [before Roe], communities of color and communities that did not have the same type of economic opportunities were the communities that suffered the most,” Boston said. She draws a parallel to the War on Drugs, insisting that prosecutors have an obligation to learn from the history of racial injustice under the law. “When I think about the mistakes that we now acknowledge around drug prosecution and how we categorized crack cocaine versus powder cocaine, that's just one example of where the law jailed one community over another. Today, as I sit in my chair, if I were to see that situation and not act differently, then what would be my role?”

Boston intends to use her discretion to decline to prosecute cases under abortion criminalization laws and points out that using prosecutorial discretion is far from a new concept. It’s her duty to work “in the best interest of the community for which I was elected to serve, and to lead with an eye toward public safety,” she said. “Criminalizing abortion undermines public safety and public trust. Further, it threatens the lives, health, and well-being of marginalized individuals whose access to safe abortion procedures will be restricted greater than others. It is my job as DA to make sure that the laws I prosecute are enforced in a fair and equitable manner without inflicting unnecessary public harm.”

However, much of Georgia’s conservative state legislature, as well as Attorney General Chris Carr and Governor Brian Kemp, are publicly committed to criminalizing abortion. Boston anticipates that they may seek to usurp the power of discretion from district attorneys. The state may implement oversight commissions designed to force prosecutions under abortion criminalization laws, or the attorney general may gain the power to prosecute alleged crimes that are currently the sole jurisdiction of the local prosecutor. “They're looking for ways to move us out, despite the votes and support our local community has echoed,” Boston said. “I'm fairly certain that will come. And the question is: how many of us will stand up and fight?”

“An oasis in the Midwest:” Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx on protecting people across state lines

Illinois is surrounded on all sides by states that either already criminalize or severely restrict abortion services or appear poised to do so. Roughly 20 percent of abortion services provided in Illinois are for a patient traveling from out of state. As the already-weakened abortion access infrastructure in the Midwest crumbles in the wake of Dobbs, that number is expected to skyrocket.

That poses a unique challenge for Kim Foxx, the state’s attorney in Cook County, which includes Chicago. She finds herself in a state with a liberal supermajority in the legislature and a vocal supporter in the governor’s office. Foxx, who herself was the chair of Planned Parenthood of Illinois from 2014–2015, is trying to leverage the relative political stability of her home state to protect abortion access for its neighbors.

Foxx is refusing to aid prosecutors in other states in pursuing criminal charges regarding abortion care provided in her jurisdiction, which means not sharing information or investigative resources. She hopes this clarity has a chilling effect on law enforcement cooperation across state lines. “By signaling that we don't believe that this is a public safety issue, and . . . using our prosecutorial discretion—which is the greatest of our superpowers—to say that we are not going to do this then, it then disincentivizes [police] wasting time and energy trying to bring that information forward,” Foxx said.

Part of that involves playing catch up. Because many abortion criminalization laws are new, prosecutors are trying to understand how exactly legislatures will pursue criminalization, and what steps can be taken to protect patients, providers, and support networks from surveillance and prosecution. “I don't know that anyone ever anticipated that we would be tracking [people’s] periods to see that they're pregnant,” Foxx said.

That means large-scale coordination between prosecutors themselves and abortion funds and advocacy coalitions. A group of prosecutors met last month in Detroit to strategize on next steps, and Foxx is working to ensure that local law enforcement agencies are not cooperative in sharing information that could target patients or providers with prosecutors out of state.

The importance of protecting abortion access is deeply personal for Foxx, who herself had an abortion and whose mother terminated a pregnancy as a teenager. “I think marrying it with my professional responsibilities to ensure public safety is natural,” Foxx said. “It is something I didn't expect to have to do, but I have been preparing for this my entire life.”

“A mighty coalition between…. working-class people, people of color, young people, and women:” Travis County District Attorney José Garza on public safety

District Attorney José Garza is unequivocal: abortion is a public safety issue. He has repeatedly pledged that he will not prosecute anyone under laws criminalizing abortion because it is antithetical to his responsibility to build a safe community.

“We know that trauma creates cycles of crime and cycles of violence. To have a legal structure that [traumatizes people] and retraumatizes victims and survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault is going to cause real harm in our communities for generations,” he said. “And the people who will suffer the most are working class women, working class families, communities of color, women of color.”

Garza represents the people of Travis County, a community encompassing Austin, Texas. He faces a conservative state legislature, a pre-Roe law already on the books banning abortions—the enforcement of which is on pause due to a court ruling—and a governor who insists on criminalization. Given the fraught political dynamic, Garza will use his discretion to protect abortion access for his community.

However, Garza’s use of discretion has led to political conflict in the past. In 2021, Governor Greg Abbott launched Operation Lone Star, a sweeping border crackdown, and Garza’s office reviewed cases under the program and declined to prosecute, calling detentions under the law unconstitutional. A state judge ultimately agreed with Garza, but the decision drew the ire of Abbott’s administration.

The possibility exists for a similar conflict around abortion criminalization laws. Garza says this highlights an abdication of responsibility from some legislatures. “Increasingly, as prosecutors, we are going to be drawn into these spaces that historically, our policymakers have resolved before they get to us,” he said. “There's obviously a breakdown that's happened. And increasingly, prosecutors will be in that space. We really have an obligation to . . . do what Spike Lee said, you know: ‘do the right thing.’”

However, if Garza does decline to prosecute someone, a district attorney from another jurisdiction or the attorney general could attempt to override his discretion and prosecute the case themselves from outside Travis County. That would be against current Texas law, as both the Texas Constitution and the Court of Criminal Appeals have been unequivocal that only elected district attorneys have the authority to prosecute state criminal charges in their communities. But some Texas lawmakers have pledged to pass legislation allowing district attorneys to prosecute abortion cases outside their jurisdictions.

For now, Garza is not focused on the threat of someone else prosecuting in his jurisdiction. “If I spent my time worrying about the bad things that the legislature was going to do, or Governor Abbott was doing, I wouldn't have time to do my work,” he said. “My number one responsibility is to keep our community safe, and so that's what I'm thinking about.” He believes very few district attorneys would support setting a precedent infringing on their power to choose what cases to prosecute. Instead, he is coordinating his efforts around abortion access with a group of other Texas district attorneys who are similarly committed to protecting it. Critically, he says this group represents about 50 percent of the state’s population.

“Abortion enjoys well over 60 percent popular support throughout the country and throughout the state of Texas. And so, here in Austin, what we’ve seen is a mighty coalition between…. working-class people, people of color, young people, and women. That’s a mighty coalition. So those lines of communication are strong,” Garza said. “Here in Travis County, we have developed progressive infrastructure. And I think there is opportunity for that coalition to be solidified across the country.”