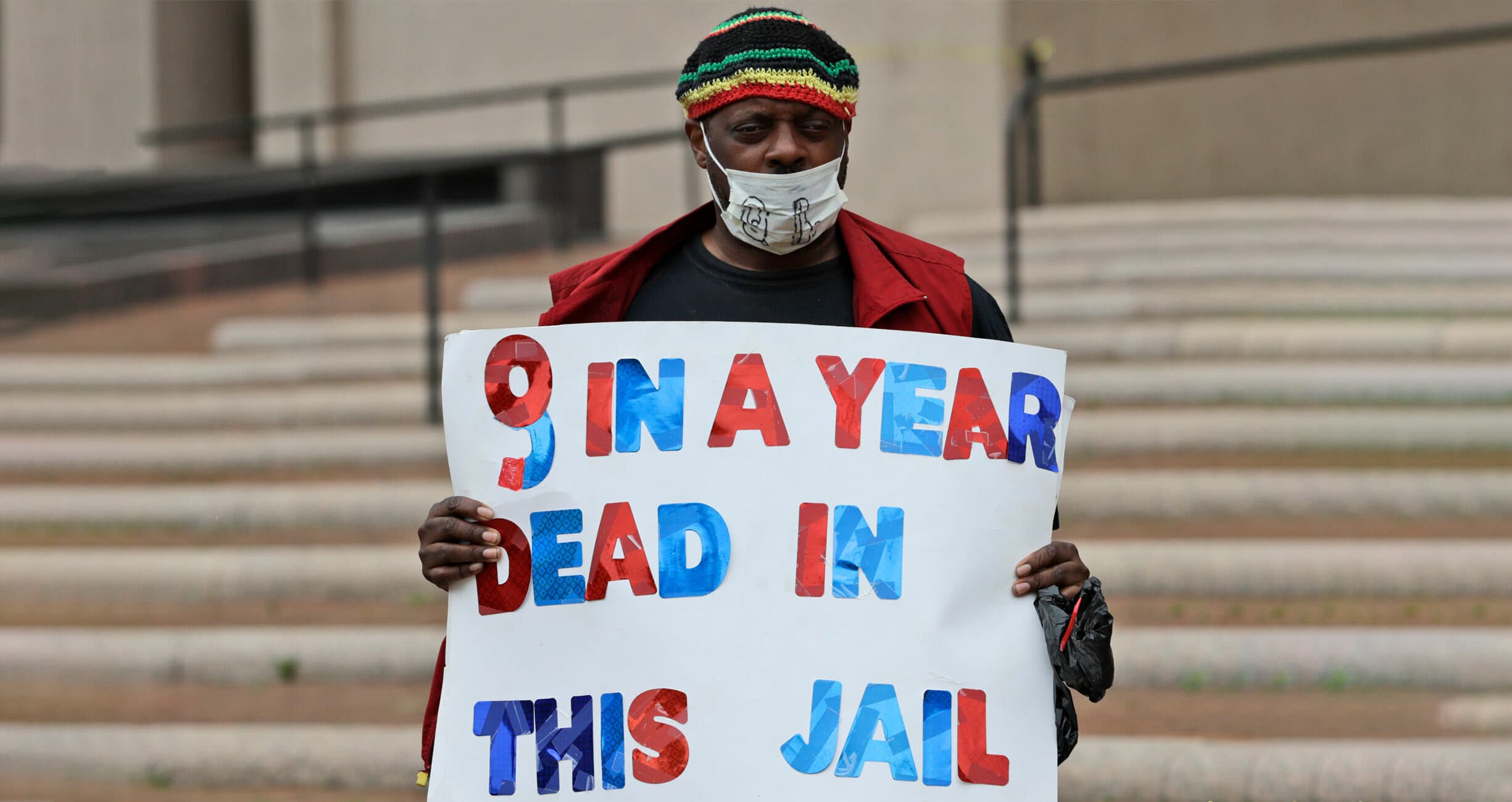

The Hidden Deaths in American Jails

Secrecy around jail deaths makes everyone less safe.

Last fall, two Pennsylvania journalists uncovered the deaths of at least 25 people statewide in 2022—deaths that were kept off official records by the jails responsible for reporting them. In some of those cases, county officials released people from custody just before they died, circumventing their legal obligation to report the death to state officials. In other cases, the county simply shirked its reporting responsibilities altogether after someone died inside its jail.

Following their investigation, the journalists created Pennsylvania’s first-ever database of in-custody deaths. That database is one of several independently run tools that track jail deaths in different parts of the country. They exist for one simple reason: jails frequently underreport in-custody deaths and obscure the conditions that contributed to people dying while in their custody.

Publicly available jail death data is deliberately opaque. The United States Department of Justice (DOJ) requires that data be collected, but not that it be shared publicly. Some counties, like those in Pennsylvania, fail to report deaths in their jails. But we know that jail deaths are on the rise; in 2020, after independently gathering data from hundreds of sources, Reuters was able to estimate that jail deaths had surged 35 percent between 2009 and 2019 despite the jail population decreasing during that time.

The frequent underreporting of jail deaths speaks to how jails function in the United States: as places for society to hide and punish people—usually those waiting for their day in court—rather than address their needs.

Hiding in plain sight

Andrea Armstrong founded Incarceration Transparency to shed necessary light on these deaths. The project, based out of Loyola University New Orleans College of Law, where Armstrong teaches, reports on the number of people who have died while incarcerated in Louisiana and supports local documentation efforts in Alabama and South Carolina.

Armstrong began building the tool after a mother whose son had died in East Baton Rouge Parish Prison asked her if her son was the only one to die that way. Armstrong simply couldn’t answer the question because nobody had kept track. If that happened in Baton Rouge, Louisiana’s second-largest city, she wondered—what was going on in less populated areas?

“We kind of do this in protest, to show that it can be done,” she said. “We’re just law professors and scrappy law students. We do this because it needs to be done. But it really is the job of, for example, our department of health, they track all types of other deaths.”

But it’s a job not being done—or at least done well—through official channels. A Senate report found that publicly available data said that DOJ data dramatically undercounts the number of deaths in U.S. jails. There are examples of local officials keeping deaths off their books across the country.

- In New York City—where the Rikers Island jail complex’s wave of deaths have garnered national media attention—an analysis found that, between the start of 2014 and July 2023, the city’s Department of Correction (NYCDOC) reported only 68 of the at least 120 deaths on its watch to the public. Since 2015, the city has operated under federal oversight following systemic civil rights abuses, and the federal monitor accused Mayor Eric Adams’s administration of hiding jail dysfunction. NYCDOC has also released people mere hours before they died in an apparent effort to keep their deaths “off the department’s count,” as the jail commissioner wrote in an email regarding one instance. Last year, the Adams administration announced that it would no longer notify the media of in-custody deaths.

- In Los Angeles, county officials report that 55 people have died since the start of 2023; however, advocates doubt that this number captures the entire death toll. Advocates say that not everyone who dies in county jails is recorded on official reports. At least one person—former NFL player Stanley Wilson Jr., who died while detained in February 2023—has not been included in the official count. Moreover, regular reporting of in-custody deaths only began in 2022, and, even then, reports failed to provide the names of people who died in custody. Autopsy results are unreliable, advocates also say. Suspicious jail deaths have been classified as “natural,” even when there is evidence to the contrary—a common practice in autopsies conducted on people who died while incarcerated.

- In West Virginia, the families of people who died in Southern Regional Jail in Raleigh County are pursuing a lawsuit against the West Virginia State Police. Fourteen people died in the jail in less than two years, and the families allege that the state police, who run the jail, are covering up information about their loved one’s deaths.

- In Oklahoma, an investigation resulted in allegations that Pottawatomie County Jail officials covered up of the deaths of seven people in their custody.

The secrecy around jail deaths makes it difficult to hold jail systems accountable and to intervene in ongoing crises. Hiding both the scope and details of in-custody deaths means those who are still alive are subject to many of the same deadly conditions. For example, if people are dying of in-custody drug overdoses, as they are in Los Angeles, officials should tell the truth about the scope of the problem. Investments can then be made in treatments that prevent future overdoses, rather than resigning to an ever-growing death toll.

“It's important that we really think about what the essential elements of transparency are,” said Armstrong. “It’s not just announcing that a death occurred, it’s a commitment to giving the most important and vital facts in a truthful manner and in a way that allows the public to understand the context of how the death occurred. The public is responsible for the operation of that facility. And so, if somebody who [died] had been receiving significant health care while incarcerated, that’s a relevant fact for the public to understand the context of a death.”

But many elected officials too often view jails as places to house people who have done “something bad.” That position ignores due process, as most people in jail are presumed innocent. It also denies people their dignity, reducing them to a charge. This dehumanizing approach invites the kinds of mistreatment—overcrowding, neglect, and violence—that lead to in-custody deaths. It also encourages secrecy about the scale of the problem.

Shedding light and providing hope

The most direct way to address jail secrecy would be to enact laws requiring transparency around jail deaths, giving both the public and elected officials a clearer picture of the scale and cost of incarceration in their communities. A bill currently before the California State Legislature would do just that—requiring officials to report important information about jail deaths to the state’s department of justice in a more timely manner. California should pass it immediately, and other states should expand their reporting requirements, too. New York State is also considering a bill to create a new oversight office, the correctional ombudsman, and another to expand the state commission of correction in order to increase transparency.

Armstrong also suggests that allowing incarcerated people to access Medicaid would provide a basic way to keep track of deaths. The program’s robust reporting and reimbursement systems help maintain a record of deaths outside of jails and prisons, but incarcerated people are currently excluded from Medicaid access. Armstrong believes including incarcerated people in the program could help address the gaps in the current reporting infrastructure.

“We can be confident in mortality data from hospitals, for example, because of Medicaid,” said Armstrong, “Because with Medicaid’s reimbursement process comes a data accountability process.”

Improving data collection should be implemented alongside the most basic solution to lowering jail deaths: stop sending so many people to jail. One way we can drive down the jail population is by investing more in community services for people in need of support and ending enforcement practices that criminalize poverty. The United States spends more than $25 billion on local jails every year while alternatives to incarceration that provide mental health care, supportive housing, and other services require more money to meet the enormous level of community need.

Shortfalls in funding leave a large treatment gap: 44 percent of people in local jails have a mental health condition. People arrested in the past year are five times more likely to meet the criteria for a substance use disorder than members of the general public. And behaviors associated with homelessness often result in incarceration. But jails are ill-equipped to treat mental health needs or substance use disorders, and jailing someone who cannot afford money bail makes them more likely to be arrested again in the future.

Jail is also more expensive than alternatives to pretrial incarceration—like supportive housing, mental health services, and substance use treatment. Jail is less effective, too, at building safety. Alternatives can break cycles of crime and incarceration without removing people from public life as they await their day in court. Further, supportive housing programs can help to reduce incarceration rates and mental health services and substance use treatment can drive down crime.

State and local officials need to make smart investments in programs that are capable of successfully supporting people who need help, rather than default to more incarceration. Doing so not only builds public safety, but also treats people with the dignity they deserve—dignity that deems no one disposable in life or death.