“The County Jail Has Always Been a Murder Ground”: Stories from Men’s Central Jail

For decades, people incarcerated in Los Angeles County’s deadliest jail have feared for their lives. With the death toll mounting, advocates are pushing to finally end the cycle of violence.

Fifty-two people have died in Los Angeles County jails since the start of 2023. The overwhelming majority of deaths have occurred in the notorious Men’s Central Jail (MCJ), which has been slated to close for years, yet remains open. Every day, more people enter its doors, most simply waiting for their day in court.

The staggering number of deaths is a product of the LA County Board of Supervisors’ inaction. In March 2021, a county working group issued a report laying out a plan to close MCJ within the next two years, and that June, the board voted in favor four to one. The county working group estimated at the time that it would take between 18 to 24 months to close the jail.

Yet, three years and dozens of deaths later, there is still no concrete plan in place to close MCJ. The structural roots of the jail’s death count—overcrowding, inadequate services, a failure to invest in alternatives to incarceration, and a culture of impunity among the sheriff’s deputies who run the facility—remain.

To mark the third anniversary of the working group’s report, and just one day after yet another death inside LA County jails, Vera spoke with organizers with Dignity and Power Now (DPN), a grassroots organization committed to finally closing the jail—and without replacing it with another. These organizers have either spent time in MCJ themselves or had loved ones die there. Each has a unique experience and future vision for a Los Angeles without the jail.

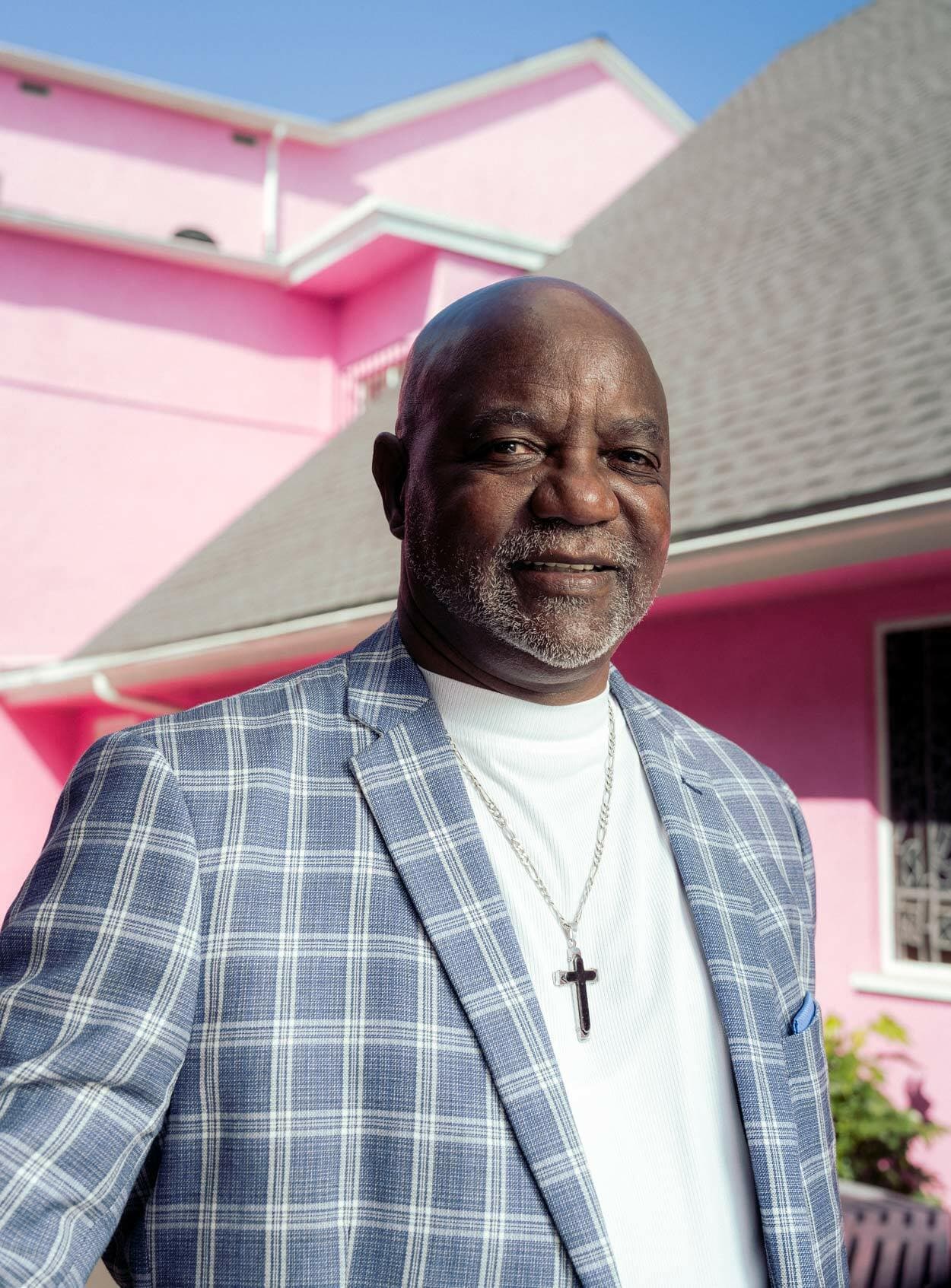

Rev. Gary Williams

Reverend Gary Williams was in and out of MCJ in the early 2000s, when he was in the throes of a substance use disorder.

“Most of my arrests were a direct result of drug use,” he said. “I did a lot of stuff out of desperation, and that got me incarcerated.”

MCJ, he said, is the last place people experiencing addiction should be sent.

“People go in there feeling bad enough,” said Williams. “But while you’re in there, you feel less than human. It’s a dangerous place. . . . And then you have the deputies and deputy gangs.

“There’s no such thing as rehabilitation in Men’s Central Jail,” he said. “It cannot be rebuilt. It cannot be changed. It needs to be torn down.”

The miserable conditions envelop you as soon as you enter county custody. The LA County Inmate Reception Center (IRC) is a disaster, with densely packed intake areas where people are forced to sleep without blankets on floors strewn with waste and garbage. It’s a common first stop for people before they are sent to MCJ.

The overcrowding does not relent when people finally make it out of IRC and are assigned a dorm in MCJ, Williams said.

“When you get into the dorm, you have a four-man cell, but there could be possibly eight to 10 to even as many as 16 men in a four-man cell with an open toilet,” he said. “Emotionally, you can’t have any kind of peace of mind when you’re in a cell with that many people. Then, if you are one of the last ones in, there might not be a bunk for you, so you’d have to sleep on the floor. It really is demoralizing and humiliating.”

The humiliation can bleed into violence. Williams said he witnessed deputies smash people’s heads against a wall for not immediately complying with an order. He watched fights break out between incarcerated people that the deputies did not seem to care about—similar to a video published last year showing staff neglecting to intervene in a violent assault for over 10 minutes.

That sort of violence is a natural byproduct of a jail run by deputy gangs and plagued by decrepit conditions, said Williams. “If you allow people to take away who you are, your dignity, your humanity, you become just somebody that’s almost invisible,” he said. “People feel less than human, and even the bullies—they’re doing that because they feel they are oppressed.”

That’s why Williams’s focus now is on expanding treatment options outside of jail. “I was facing 16 months of state prison time at 46 years old,” he said. “I told my public defender that I had a drug problem, and they got me into a drug court. And that saved my life. I didn’t go to prison; I went to a jail treatment program.”

Williams wants others currently held inside MCJ to have the same opportunity. Providing treatment programs outside of jails can support people with mental health and substance use needs in a way that MCJ is simply unequipped to— without risking their life or denying their freedom in a deadly facility. Forty-one percent of people in LA County jails have mental health needs, and researchers have found that 61 percent of people taking psychotropic medications or housed in specialized mental health units there could be safely diverted into existing incarceration alternatives.

Los Angeles already has programs in place that can meet those needs—if they are properly funded. The county board of supervisors created the Office of Diversion and Reentry (ODR) in 2015 to provide these services. Since then, it has diverted more than 8,500 people from county jails into community support systems, providing essential stability to people as they recover. But ODR needs more beds, and the county should invest in expanding ODR and permanent supportive housing as a complementary measure to closing MCJ.

The American Civil Liberties Union successfully sued the county for failing to provide adequate mental health support, and, as part of the settlement, the county is required to add another 1,925 community-based beds as an alternative to incarceration. Williams said this expansion—coupled with closing down MCJ—can help build a safer Los Angeles.

“To be in a community-based facility is a whole different feeling,” he said. “It would do something for people’s humanity, for their emotional well-being, to know that they’re right in their own community getting the kind of help that they need. . . . They can be liberated and freed from that mentality that the only way out is incarceration. Some people are just institutionalized. This would deinstitutionalize them.”

But as long as MCJ is open, incarceration is likely to remain the county’s default response to the mental health and substance use disorder needs Angelenos face. The county has shown that, as long as it is still able, it intends to fill the jail to, or even beyond, capacity. That’s a recipe for more death.

“MCJ is broken down, it’s the worst [jail] of all,” said Williams. “They’ve been talking about closing it for years. There has to be a better way to use the resources than to continue to hold people in a place that takes away your humanity; that robs you of your identity.

“I believe it’s time for Men’s Central Jail to be closed.”

Helen Jones

Tragedy brought Helen Jones to the fight to close MCJ. Her son, John Horton, died there in March of 2009 at the age of 22—one of 38 people who died in county jails that year. The LA County coroner’s office ruled his death a suicide, despite evidence of a “fresh intra-abdominal and back muscle blunt force injury.” Jones said her son was murdered, and sued the county in a case that was settled for $2 million.

Horton was held on a low-level, nonviolent drug charge and had agreed to a plea agreement that sentenced him to two years in prison. Jones and Horton were both comfortable with that outcome—Horton was going to spend that time working as a firefighter. But Jones said she was still scared for her son’s safety.

“Something just let me know—I guess mother’s intuition—that I didn’t think he was going to make it,” said Jones.

While Horton was waiting to be transferred from MCJ to prison, sheriff’s deputies began holding him in solitary confinement—a dimly lit room with just a bed in it. When Jones tried to visit him at MCJ, the deputies stonewalled her and were opaque about where he was being held.

“I put in the visiting form every day, and it just got denied,” said Jones. “I didn’t get the chance to visit, except for just one time.”

Jones tried to visit her son again the following day, but was denied, with no reason given. “He was in MCJ for 30 days, [and I only got to visit] one time,” she said. “I knew something was going on,” she said. “Other families have been in there, and they said that’s when something is going on. They’re not letting you visit him, and they should know exactly where he is.”

Now, said Jones, the reason is clear: “It was because they were already abusing him.”

After 30 days of being turned away by the jail, sheriff’s deputies notified Jones that Horton was dead. Jones immediately had questions: Where did he die? How did nobody see what happened?

The deputies didn’t offer many answers, but some were left on Horton’s body, however. When she got her son’s body back, she, along with her husband and best friend, pored over him, noting all his injuries: a handcuff mark rubbed raw, trauma to his head, trauma to his torso. If he was in solitary confinement, how did he get all these injuries?

“They beat John, and they left evidence all over his body,” said Jones. “They hit John in there with a flashlight, left the print of the flashlight on his forehead. He had a blood clot; they broke his nose. They busted his liver, busted his kidney, busted his pancreas, busted his intestines. They severely injured his pelvis, busted a two-inch muscle in his back. [There was] a big scar on his shoulder where the skin was off. [They] busted his lip.”

That’s when Jones filed her lawsuit. Aside from the settlement, her case exposed a pattern of behavior by sheriff’s deputies that led to Horton’s death and the deaths of dozens of others in MCJ.

“The lawsuit showed that they make stuff up,” said Jones. “They put a case on someone, charge them with fake cases, and get them even more time.” She notes that the deputy gangs drive the violence. “[Another] thing the discovery process showed is that they’ve been beating inmates for years,” she said. “This is part of their gang activity. . . . What I learned from the 3000, the floor John got killed on, is that even high lieutenants and sergeants couldn’t even go on that floor because [other] gangs ran that floor.”

Jones’s lawsuit also exposed the county coroner’s complicity in covering up violence in county jails. When researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) later dove into the autopsy reports of 59 deaths in Los Angeles County jails between 2009 and 2019, they found that the majority of cases ruled “natural deaths” included evidence of physical violence. UCLA’s report concluded that “the majority of Black and Latinx men are not dying from ‘natural causes’ but from the actions of jail deputies and carceral staff.”

“I just want our system to stand up and hold the sheriff accountable,” Jones said. “The sheriff’s department will just tell you, ‘We’re elite, we’re untouchable, nothing can be done to us.’ And you know, they’re right, because nothing is being done.”

But Jones is working to change that. Since becoming plugged into DPN’s work in 2017, following a wave of deaths in the county jails, she has tirelessly organized to close MCJ, and to remind the board of supervisors of the people whose lives the jail has already claimed, like John.

“MCJ is a graveyard,” she said. “You’ve got thousands of people who have died in MCJ. How can that continue to be a jail? There’s no reforming it. . . . Nobody should be dying in jail under any circumstances. All the deaths that happened in jail are preventable. . . . It’s just sad that our county board of supervisors are sitting back. You’re losing 40 or 50 people or more a year.”

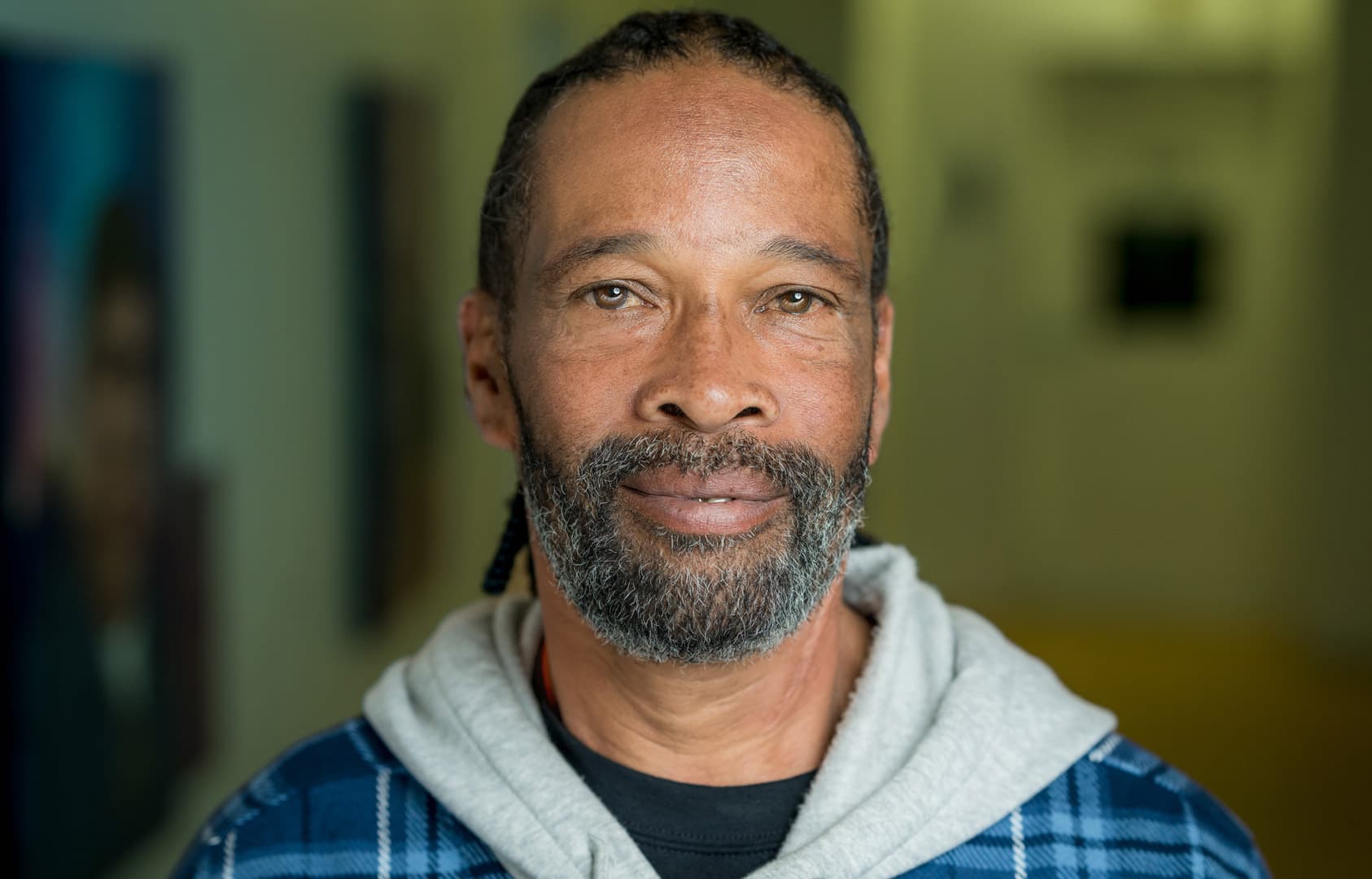

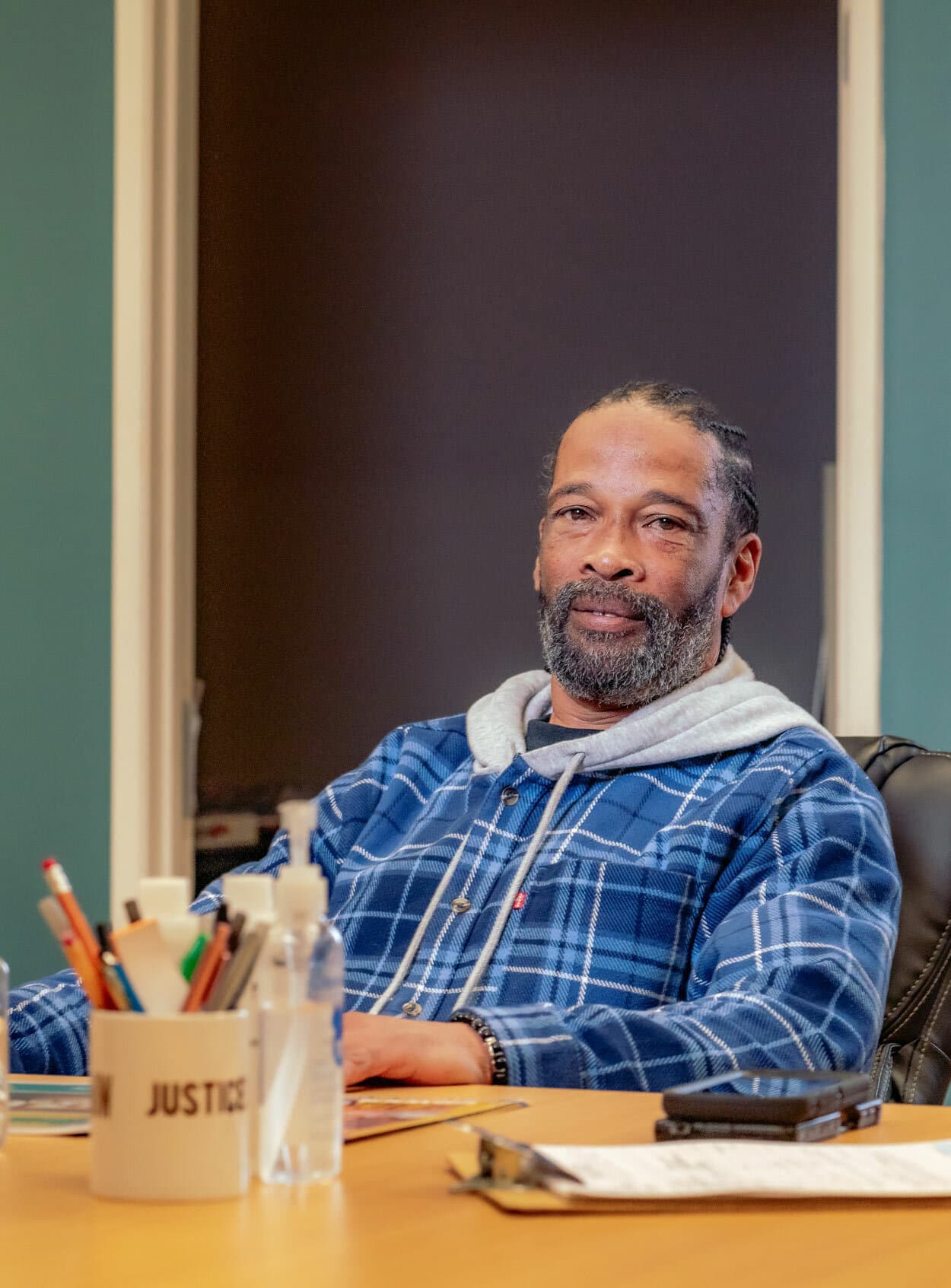

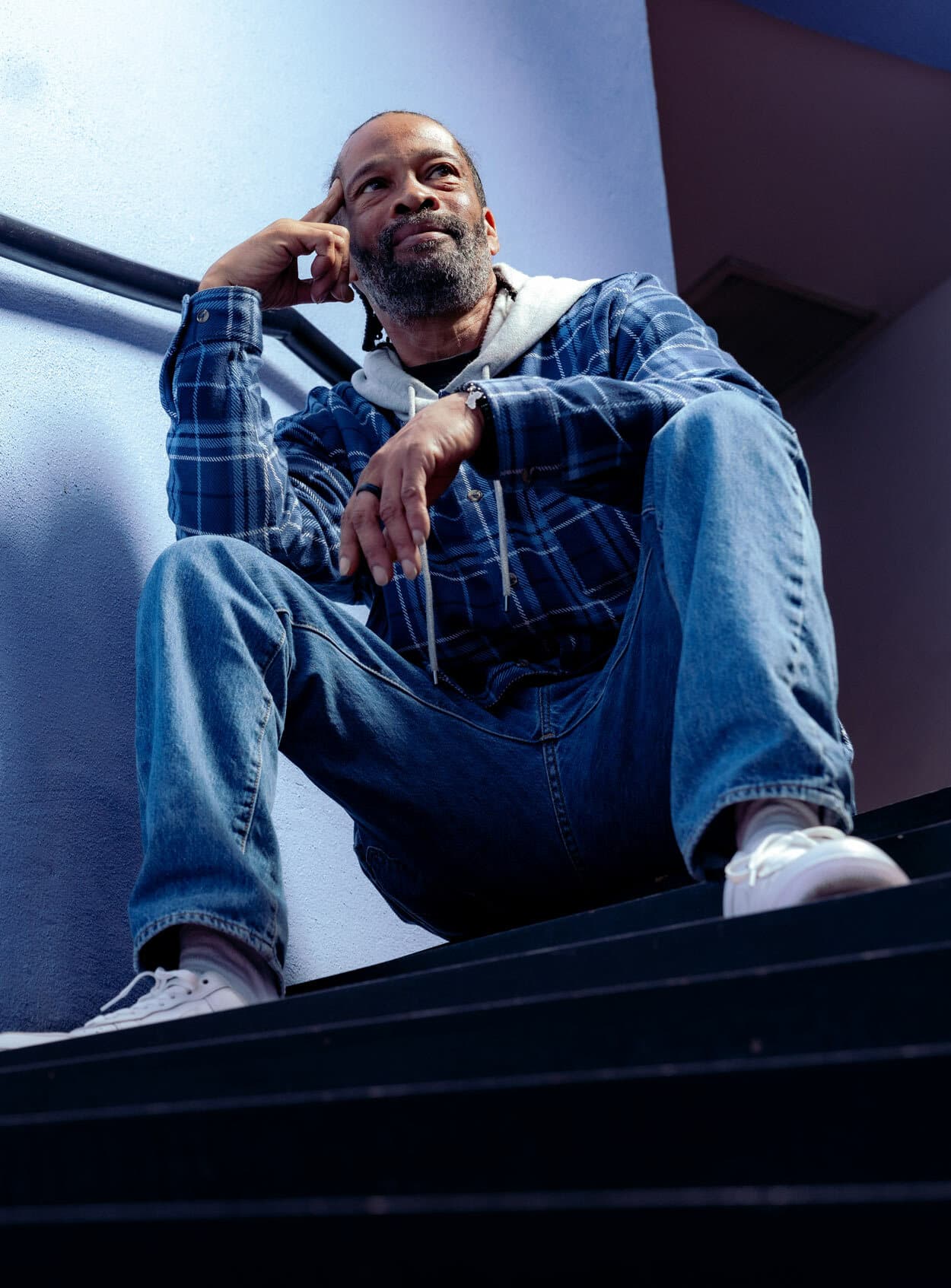

James Nelson

“The county jail has always been a murder ground,” said James Nelson, program and organizing lead at DPN. “People have always come up missing.”

That was true in 1986, when Nelson was held in MCJ for several months while awaiting trial. And it’s true now, he says, based on his work with families of people currently inside, and with people who’ve recently been released.

Growing up in Watts, Nelson was a member of a local gang. That association led the police to accuse him of a crime he said he did not commit. He wound up in MCJ, desperate for his day in court to prove his innocence. But before he could do so, he had to bear the wretched conditions and constant violence inside MCJ.

“It was major abuse in MCJ,” he said. “We were not fed well. You were sleeping on the floor, sleeping on the roof. People would get beat up for nothing. [Once,] this guy and his [cellmate] were just roaming. That’s what you call it when you get up and walk around because you’re tired of being locked up in a cage. And this guy was killed just for roaming around. The [sheriff’s deputies] beat both of them up. One of them made it back, but his celly was killed, his neck was broken. They told his family that they had handcuffed him and that he fell down the escalator. But we knew the truth.”

Nelson said this kind of violence is a matter of routine. It doesn’t matter who you are—once you’re in MCJ, you’re at the mercy of the sheriff’s deputies who run the jail. And they are a gang unto themselves.

“An FBI [informant] came up missing in the county jail,” he said. “He was investigating the sheriff, and he went through what [other incarcerated people] go through—they took him to the back of the jail somewhere.”

The violence inside MCJ is driven by a lack of accountability that runs through county’s sheriff’s deputies.

“[The deputies] have that gang mentality,” said Nelson. “They function like a gang, they behave as gang members. They cover stuff up. They wrongfully kill people . . . because, for so long, nobody was being held accountable for their actions. You’ve got so many people who don’t even call the sheriffs because they know what they’re doing . . . . Taxpayers are paying these people to commit crimes against them.”

That the sheriff’s deputies operate as gangs is a bitter irony not lost on Nelson. The Los Angeles Police Department division that arrested him was implicated in a scandal of systematic violence, killings, false arrests, coverups, and perjury that surfaced in 1998. When Nelson was arrested and sent to MCJ, the sheriff’s deputies operated the jail with the same sort of violence and corruption. Last year, the Civilian Oversight Commission, created by the board of supervisors as a check on the sheriff’s department, called the deputy gangs “a cancer.”

The deputy gangs impose their violent power in ways big—like hiding an FBI informant in the labyrinthine jail—and small—like petty intimidation. From his time at MCJ, Nelson recalls a picture of John Wayne hung on the wall, which the deputies used to intimidate those held there. “If you looked at the picture, they were going to take you out of the line and take you somewhere,” he said. “One guy touched the picture, and they beat him good.”

“They also try to deflect stuff,” he continued. “People ‘commit suicide,’ but bodies come home and are beat up, their internal organs are busted. How did he hang himself, but everything in his body is busted up?”

When Nelson finally did get his day in court, he was convicted and sent on what he calls a “tour of California”: a stay in every prison in the state that was open at the time of his incarceration. But despite years of incarceration, in every corner of the state, it was the overcrowding, decrepit conditions, and pervasive violence at MCJ that stayed with Nelson. That’s why, as soon as he was released, he began organizing against the injustice there.

“There’s really no difference [in MCJ] between then and now,” he said. “The only difference is more people are dying now than were dying in the ’80s . . . . The same behavior, the same treatment, the same living conditions. People get sick and can’t get adequate medical attention. It’s infested with rats. It’s just filthy, not livable for anyone. It needs to be closed.”

Nelson is currently working toward that goal at DPN, connecting with families impacted by MCJ and the terror of the sheriff’s deputies. “You’ve got so many families out here thinking that they had to fight up against this sheriff’s department by themselves. They feel powerless. So, we connect with family members,” Nelson said.

Slowly, they are winning a future for Los Angeles that puts care at the fore, rather than incarceration.

“We went to the community and the community wanted alternatives to incarceration,” said Nelson. “They asked for ODR, where they can go and get help, and not jail, for whatever they’re going through. If they’re going through substance abuse [now], they go to jail for it. That’s an illness. Why are you going to jail because you’ve got an illness?”

Now, the challenge before Nelson is getting the board of supervisors to follow through on its plans and finally close MCJ.

“It’s just not livable; that’s why the board of supervisors agreed years ago that it needs to be closed,” said Nelson. “But now we’re in this closing phase, and nobody knows how to close it . . . . The county really needs to look and be brave . . . [and] do the right thing.

“How are you going to be in a position of power and stay silent?”

Photos by Mike Dennis.