Staying Connected When Your Loved One Is in Prison

Despite prison walls, families fight for connection during the holidays and beyond.

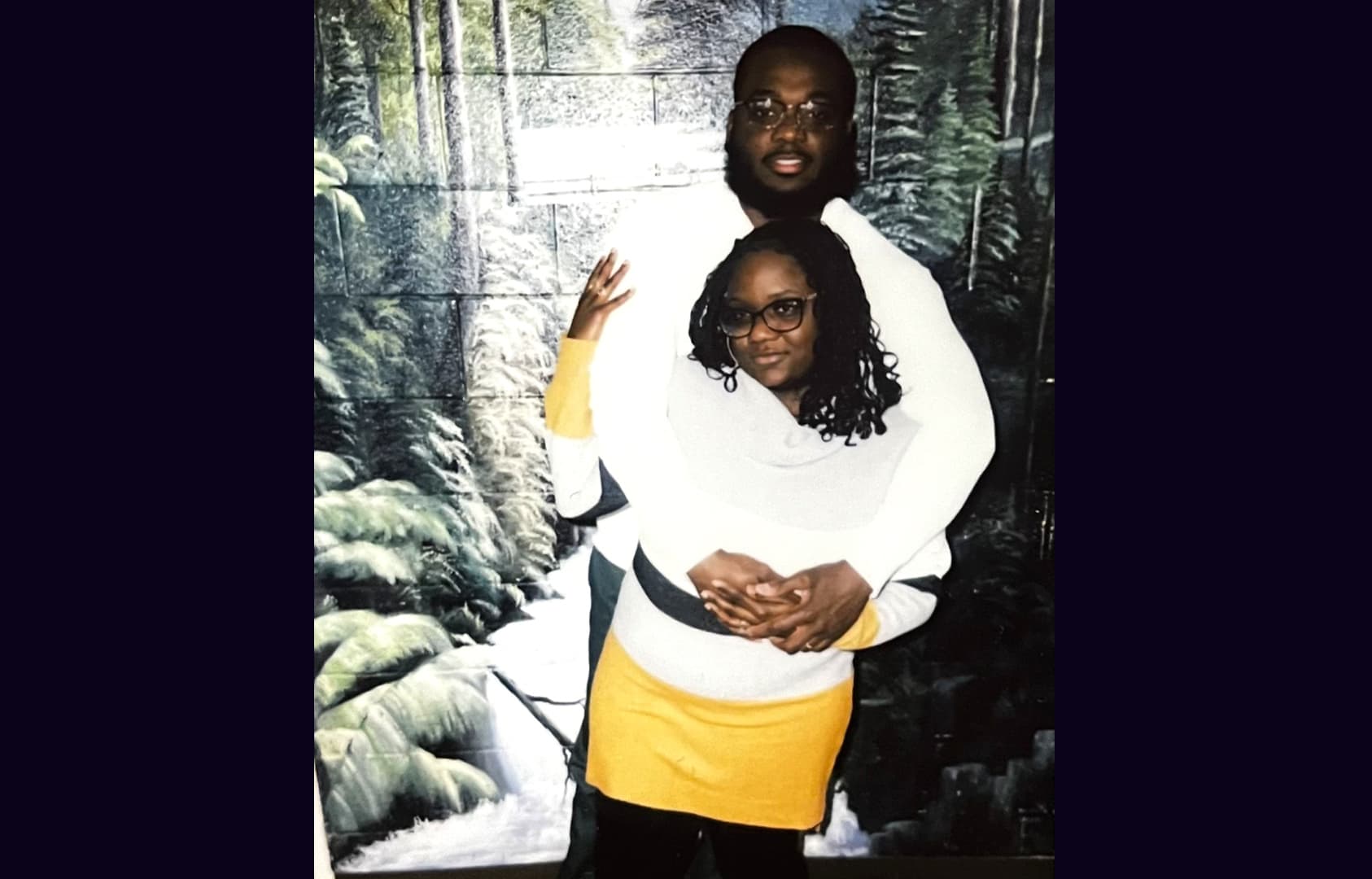

Mon’e Jackson-Cross signs the presents under her Christmas tree, “From mom and dad.” Her husband can’t shop from the Wende Correctional Facility in Western New York, but he asks for photos of the sneakers or toys she is considering so that he can help decide what to gift their children, who are among an estimated 2.7 million kids with a parent behind bars.

It’s always hard to have a loved one in prison. And during the holidays, it can be excruciating. Yet the families of the nearly 2 million people who are incarcerated in the United States find ways to stay connected.

When prison walls aren’t the only thing separating families

Before she could afford a car, Donna Robinson would visit her daughter around the holidays by taking a seven-hour bus ride from Buffalo to Manhattan, catching the Metro North train, and then getting a cab to the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women in Westchester County, New York. She would make special effort to bring her daughter’s children to an annual holiday celebration at the prison, where they were spared some typical visitation restrictions and could hug their mother as much as they wanted.

The United States continues to unnecessarily separate millions of children from their parents through incarceration even though better options exist. More than half of the women incarcerated in state and federal prisons are mothers to minor children. And though women’s incarceration rates are rising, jails and prisons fail to meet women’s specific needs; for one, women are more likely than men to be imprisoned far from home.

Communities most impacted by mass incarceration have the fewest financial resources, so it can be very difficult to visit remote prisons. “They lock [them] up and move [them] 300 or 400 miles away from [their] loved ones,” Robinson told Vera. Life has gotten easier now that she has a car and can drive the six hours to visit her daughter. Robinson and other family members arrive right at the start of visiting hours at 8:30 a.m. and stay until visiting hours end at 3:30 p.m. “[Staff] laugh at us about playing Uno for eight hours, but this is what we do,” she said. “It gives us a chance to laugh.”

Finding connection through food

Robinson’s daughter has four children, as well as one grandchild, of whom she has only seen photos. This past Thanksgiving—knowing that her daughter was likely spending the holiday on lockdown, confined to her cell—Robinson didn’t feel like cooking.

“Holidays are really hard,” she said. “I felt like, ‘Why should I buy all this food and cook all this food? I don’t even know if she is eating tonight?’”

The food her daughter usually gets is not healthy, Robinson said. “Everything is overloaded with sodium. It has no nutritional value except to fill up your stomach. On the holiday, they might give them a slice of turkey breast lunchmeat—something you make a sandwich out of—and instant mashed potatoes.”

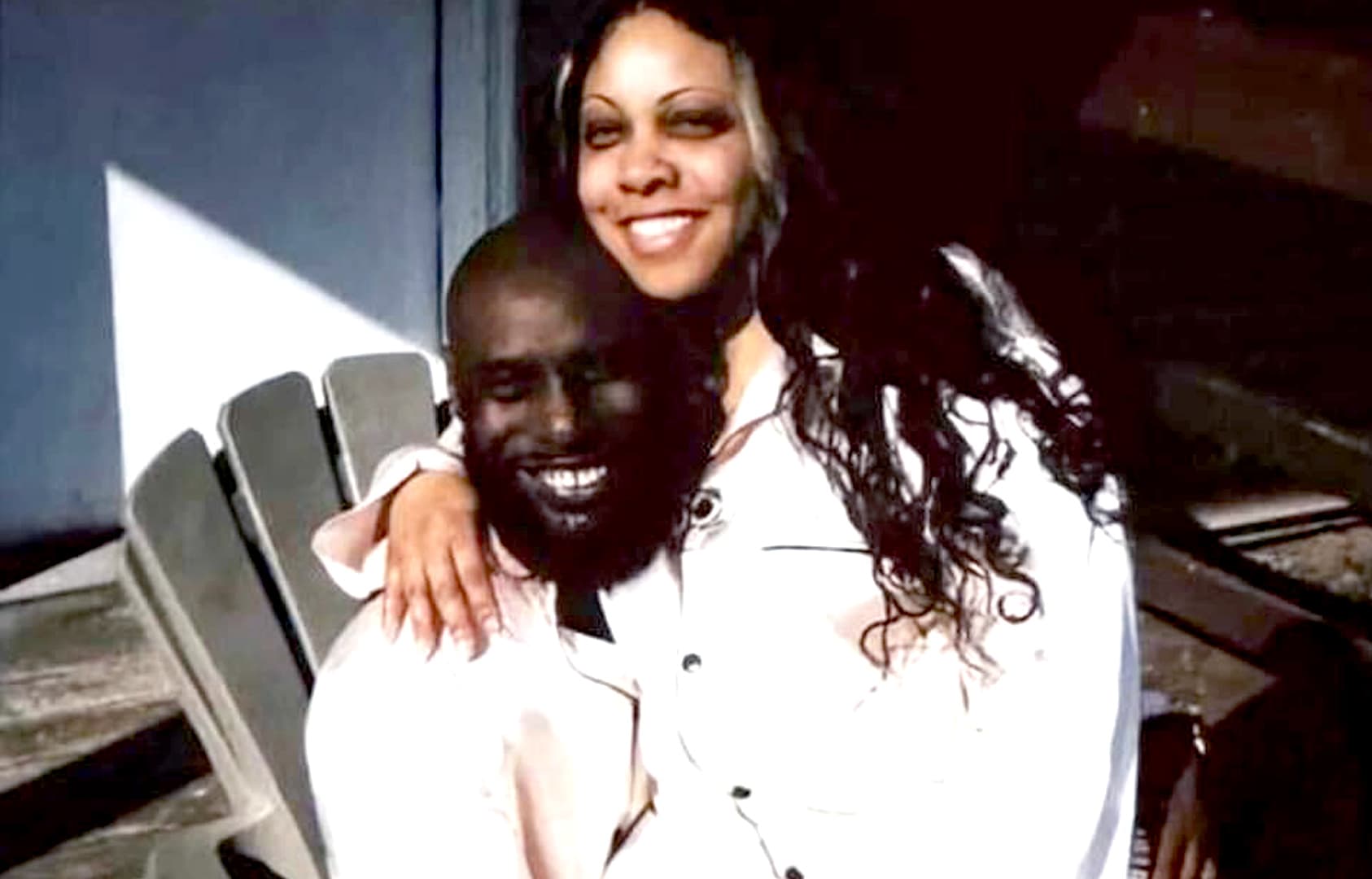

Catherine Johnson-Peoples is allowed to bring food to cook during family reunification visits with her husband, who, like Jackson-Cross’s husband, is incarcerated at Wende Correctional Facility. For Thanksgiving, she made turkey, stuffing, and macaroni and cheese. Johnson-Peoples treasures the opportunity for the two of them to take photos together, but she says it’s difficult to leave. “I don’t turn around when I am leaving anymore,” she told Vera. “I don’t like turning around and looking and seeing him sitting there and knowing he that he can’t leave. . . . Every holiday they lock them down. It bothers me because he is already in prison; it’s already depressing enough.”

Life beyond bars

Most people who are incarcerated will eventually return home to their communities. Decades of research shows that maintaining healthy family ties helps improve people’s health and behavior and decreases the odds that they will return to prison. Yet, there are far too many barriers and restrictions for family contact.

With her husband unable to see the presents he helped pick for their children, Jackson-Cross echoed that holidays are especially difficult. “It’s hard when he is not there to open gifts or get the typical family love.”

She wishes that she could take the entire family to see him at the holidays. Due to visitation regulations, Jackson-Cross can never take all her children to see their father at once. “I don’t think there has ever been a visit when he has seen all [of them together],” she said. “I bring all the girls, and then all the boys go. They take turns.” It’s not easy for the children to go through the inspection and barbed wire gates of the prison, but they cherish their visits, spending time playing their father’s favorite card game, Speed.

In between visits, families try to lean on happy memories and look toward a future of freedom and reunification.

“I dream about the day my daughter will be released. I am probably going to have to get somebody to drive me down there because I would probably do 100 miles an hour all the way,” said Robinson. “All she wants to do is to come home and read stories and be a grandma. That is my wish and my prayer and all I am living for.”