Prisons and Jails are Violent; They Don’t Have to Be

Incarcerated people endure violence that makes us all less safe—but proven solutions centered on human dignity exist.

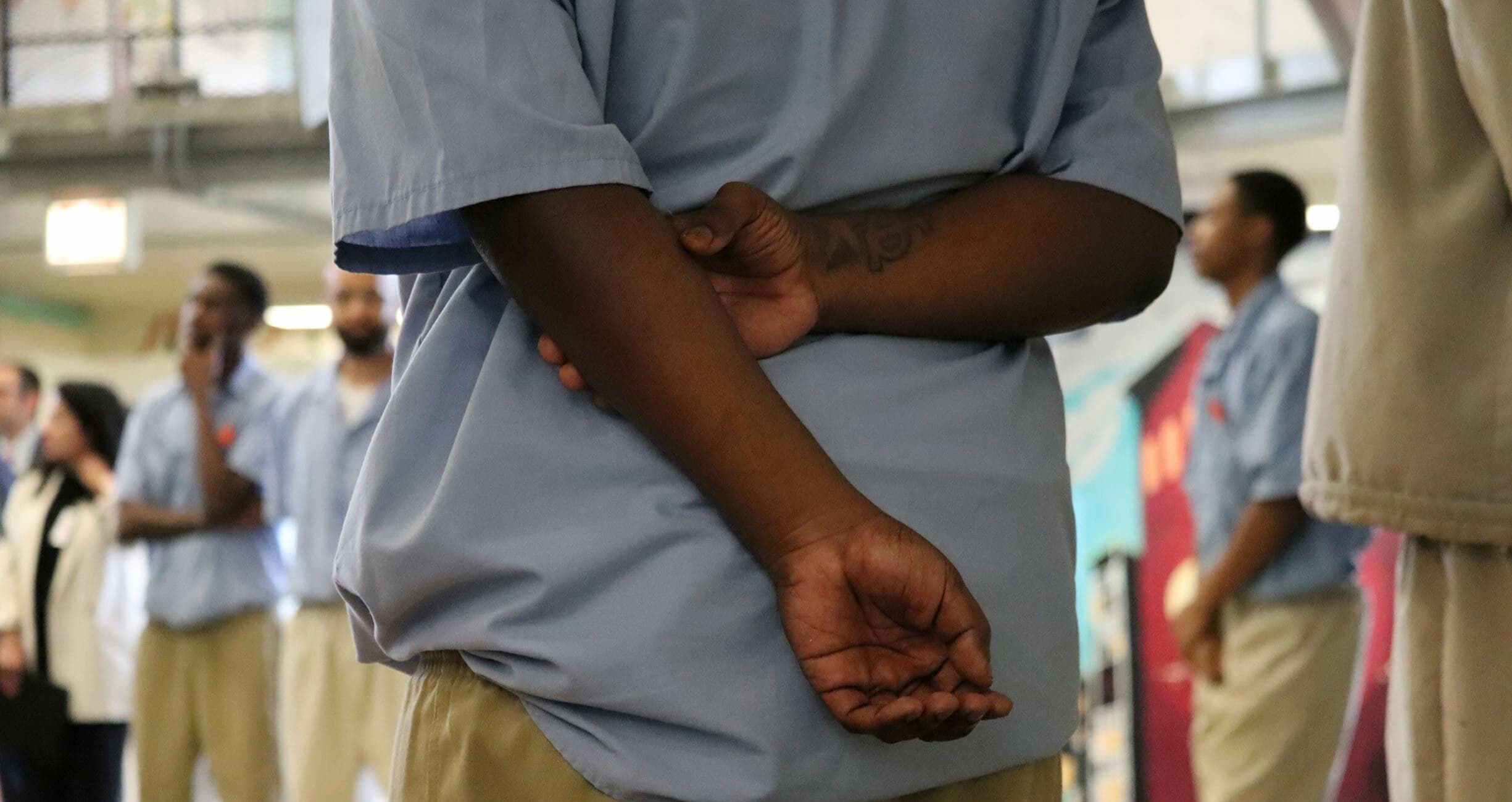

Jails and prisons, often overcrowded and understaffed, are frequently dangerous, dehumanizing, and traumatizing places where violence is largely “unavoidable.”

Take, for example, Illinois, where frequent reports of violence and abuse led the Federal Bureau of Prisons to announce the closure of the Special Management Unit at the Thomson federal penitentiary earlier this year. The allegations included reports of incarcerated people being chained by each limb to their bunks for hours.

In California, at least 37 people have died in Los Angeles County jails so far this year. One video shows staff at the county’s Men’s Central Jail failing to intervene in a violent assault for 14 harrowing minutes.

In New York, a Marshall Project review of disciplinary records found that corrections officers mistreated incarcerated people in various ways, such as withholding food and beating them. The resulting injuries included shattered teeth, punctured lungs, and broken bones.

And there are many more examples of how people either directly experience violence or become witnesses to it while incarcerated. These encounters threaten their physical and mental health. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, “Exposure to violence in prisons and jails can exacerbate existing mental health disorders or even lead to the development of post-traumatic stress symptoms like anxiety, depression, avoidance, hypersensitivity, hypervigilance, suicidality, flashbacks, and difficulty with emotional regulation.” Meanwhile, resources and treatment options to help people manage these symptoms are woefully inadequate, given the state of health care behind bars.

The effects of this violence impact not only everyone forced to live in these settings but those who work in them as well. A 2012 study reported higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder among corrections officers.

The impact of incarceration far outlasts whatever time people spend behind bars. The inhumanity of U.S. jails and prisons—the physical violence and abuse, as well as unsanitary conditions and low-quality health care—means people can leave incarceration in poorer physical and mental health than when they entered. More than 95 percent of people in prison will someday return home, but prisons fail to prepare people for a successful life after release. Instead, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, the current U.S. criminal legal system apparatus “routinely and persistently fails to produce the fair and just outcomes that will make us all safer.”

Changing the Environment

Although jails and prisons face different obstacles to reducing violence, there are solutions that can decrease violence in these facilities.

For example, improving the inhumane conditions people must endure while incarcerated can decrease the likelihood of violence. Research shows a correlation between rising temperatures and an uptick in violence in prison. Yet many U.S. jails and prisons lack air conditioning, trapping people in concrete and metal structures that provide no reprieve from dangerous triple-digit heat during the summer months. In addition, poor nutrition—jail and prison diets are notoriously unhealthy—has also been linked to violent behavior. A 2002 study in the United Kingdom concluded that a healthy diet with adequate levels of vitamins, minerals, and fatty acids can reduce antisocial behavior, including violence, in prisons.

Prison administrators can also work to reduce violence in their facilities by providing programming that improves quality of life. Vera’s Restoring Promise initiative is working with correctional partners in five states to repurpose existing housing units into places that are grounded in accountability, dignity, and healing for young adults. This work is co-led by Vera and the MILPA Collective.

At one of those units, the Community Opportunity Restoration Enhancement (C.O.R.E.) unit in South Carolina’s Turbeville Correctional Institution, older men with lengthier sentences mentor young adults between the ages of 18 and 25. The housing unit has walls adorned with murals, windows that allow natural light in, and rooms covered in photographs. Incarcerated people in these units spend as many as 15 hours outside their cells and participate in classes focused on life skills, financial literacy, conflict mediation, and nurturing healthy relationships with family and loved ones.

This approach has resulted in less violence and a safer environment for all. Living in a Restoring Promise unit during their incarceration decreased young adults’ odds of being convicted of a violent infraction by 73 percent. Unpublished data from Restoring Promise sites also reveals benefits for corrections staff, with 89 percent reporting improved quality of life while working in the Restoring Promise units.

“Restoring Promise is a different atmosphere and allows a sense of freedom . . . a sense of peace,” said Zo Stanton, a member of the research team at MILPA and a former mentor in Restoring Promise’s other South Carolina unit, Cadre of HOPE. “You can walk around and not have to look over your back.”

Higher education programs may also help to reduce violence and create safer conditions for incarcerated people and staff. Completing vocational training, apprenticeship programs, GEDs, or college classes can also provide opportunities upon release that reduce the likelihood that someone returns to prison.

And finally, although it is necessary to improve current conditions, the most effective way to heal families and communities while also reducing the number of people behind bars in overcrowded environments is decarceration. On any given day, more than 400,000 people are detained pretrial. Many remain jailed not because of the danger they pose to their communities but simply because they cannot afford bail. According to research by the Brennan Center for Justice in 2016, nearly 40 percent of the U.S. prison population—576,000 people—were behind bars for no compelling public safety reason. Bail and sentencing reforms are a few of the many necessary changes that would help reduce jail and prison populations.

Jails and prisons, in their current form, perpetuate violence and abuse. A humane approach, rooted in dignity, will make jails, prisons, and our communities safer.