Planting Gardens Behind Bars

The pandemic halted most in-person activities and opportunities in jails and prisons—like classes, religious services, and art programs—all of which made life for incarcerated people bearable. As a result, people who have endured incarceration as COVID-19 has spread have lived in a state of extreme isolation and idleness.

“Men speak about feeling empty or without purpose, a void that was once filled by various programs, personal development classes, and religious services,” wrote David Sell this past May. Sell has spent the pandemic incarcerated at Wende Correctional Facility in Alden, New York. “Souls were depleted when these programs were suspended, and many people are struggling to maintain positive attitudes.”

Therapeutic opportunities are badly needed for anyone who has endured long-term isolation—which can harm physical and mental health—and especially for those who have spent the pandemic locked away from their loved ones and communities. As COVID-19 vaccines allow for safer interactions, it is critical that meaningful opportunities for people to grow be restored and expanded in U.S. jails and prisons.

Far too many people are incarcerated in the United States, and our model of punishment doesn’t work. In cases where incarceration does occur, jails and prisons should be centered around personal growth rather than inhumane punishment. Prisons have walls, but they are hardly cut off from their communities. Ninety-five percent of people in state prisons will be released and return home at some point. It is crucial that their humanity is not stripped from them while they’re behind bars.

When prisons and jails foster cultures of deprivation, fear, violence, and exploitation, people leave worse off than they were when they arrived. Dehumanizing punishment does not make us safer, but positive education and workshops do. People who participate in postsecondary education in prison, for example, are 48 percent less likely to recidivate than those who don’t.

The criminal legal system should be investing in opportunities for people to develop their personal potential while behind bars. Yet, even before the onset of COVID-19, there was a general lack

of consistent and meaningful activities in carceral settings. As social distancing and pandemic precautions halted the few programs that did operate, some organizations sought creative ways to fill the void. Unconditional Freedom Project (UFP), through its initiative to turn prisons into monasteries, created a correspondence course that linked an incarcerated person with a volunteer pen pal on the outside. Together, they study Art of Soul Making, a curriculum that focuses on meditation, journaling, and selected readings on contemplation, purpose, and eudaimonia (or well-being).

“It’s nice to be able to communicate and connect with someone who sees me as a person with a soul,” wrote Tami Jade, a participant who shared her thoughts in Remembering, a reflection book about the program. “I think that’s overlooked in here far too often, and that if there was more understanding and compassion it would be so much more helpful and beneficial for people’s real rehabilitation and growth.”

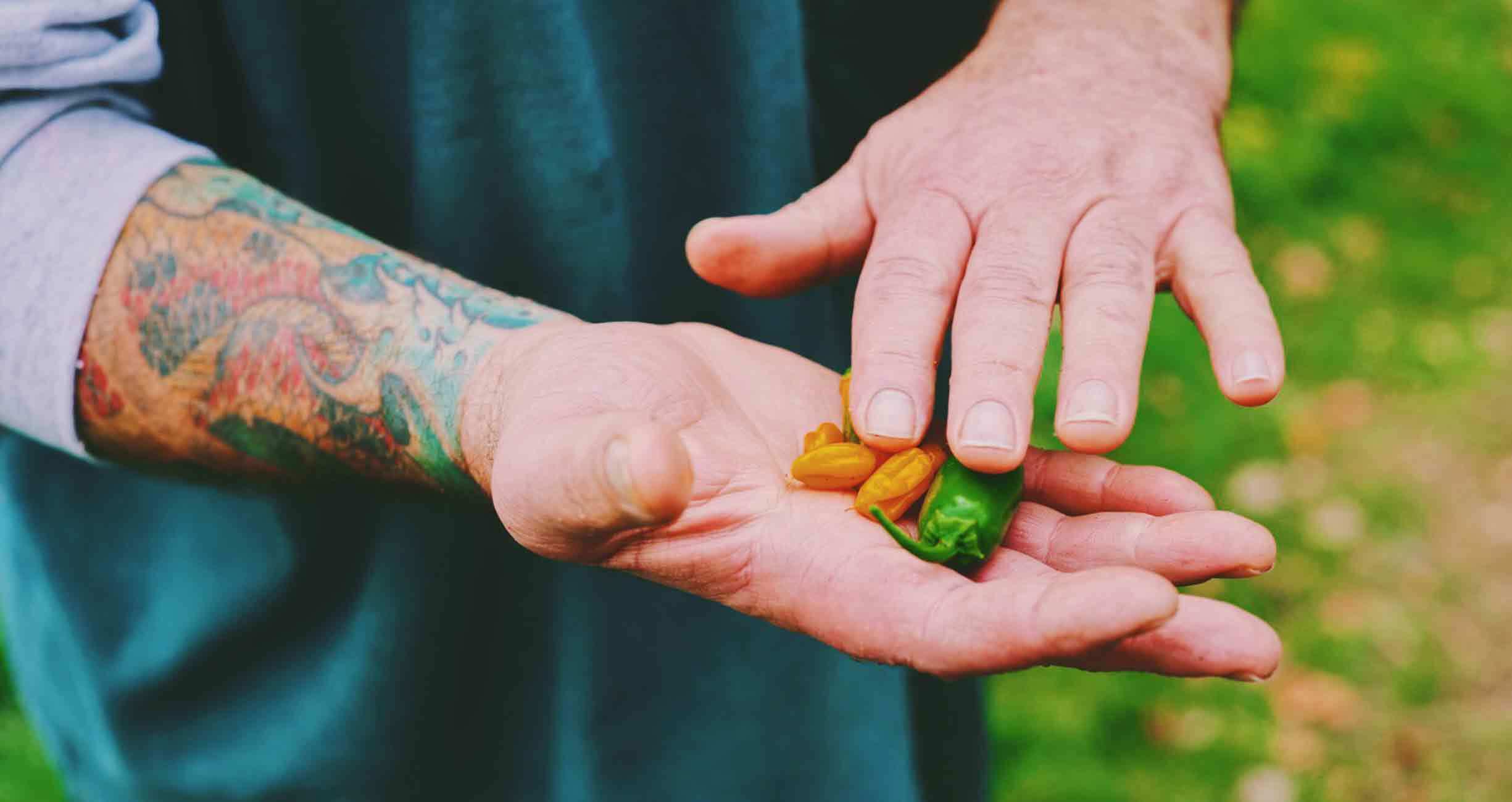

As visitation has become more available over time, representatives from UFP have begun in-person programming in jails and prisons in California. At the Mendocino County Jail, they spend their time working with incarcerated people on projects like beekeeping and building chicken coops and gardens. Earlier this year, UFP secured enough donations from the community to hire a full-time garden coordinator. The produce grown in the garden accounts for 10 percent of the produce used in meals in the jail.

“We are all a community; we are affected by what happens in the jail,” said Kate Feigin, who works as the restorative justice manager at Mendocino County Jail. “These are our neighbors, so it really behooves all of us to invest in our own collective well-being.” Feigin comes from a social work background and stresses that jails should foster a culture of community wellness.

“People often come to jail feeling very numb and disconnected,” said Feigin. “These interactions are an opportunity for people to learn something new and get more deeply rooted and connected with both themselves and others.”

Participants at Mendocino County Jail are encouraged to see themselves as beekeepers and gardeners, rather than the negative terms used for people behind bars, and can even earn beekeeping certificates that can be used when they’re released.

“The human connection is so lacking in correctional facilities,” said Feigin. “It is dehumanizing to not be able to connect with other beings. We really need each other.”

In too many prison systems, volunteers and outside activity coordinators are still not being allowed to enter facilities, despite the risk reduction provided by vaccines. “Restrictions on religious volunteers and volunteers for enrichment programs should be lifted,” wrote Sell. “Facilities must offer an effective means of counseling, and programs should do more than look good on the face—they must also accomplish good and contribute to people’s growth.”

Combining ecological restoration projects with personal development activities for prison residents, according to UFP Executive Director Marcus Ratnathicam, helps “rewild nature and rehumanize society.” UFP sees the problems of environmental degradation and human suffering within prisons as part of the same overall problem. “We discard our trash into nature and discard our ‘trashy’ people into prisons. But we need to restore nature and people, because both human and natural diversity are key to our thriving as a species.” UFP views prisons as institutions that should foster penitence, contemplation, and personal reflection.

It is simply inhumane to keep people idly caged in cinderblock cells without access to fresh air and sunlight. This does terrible harm to people already being harmed by mass incarceration, and it is detrimental to society. Opportunities for education and social engagement for incarcerated people are true investments in public safety. It’s time for more of them.