Series: From the President

More Than Half a Million People in Prison May Soon Be Able to Afford College

This fall, Jessica Henry will join the millions of people starting school again. She’s set to graduate in the spring, with a bachelor’s degree in social work and a double minor in business and psychology.

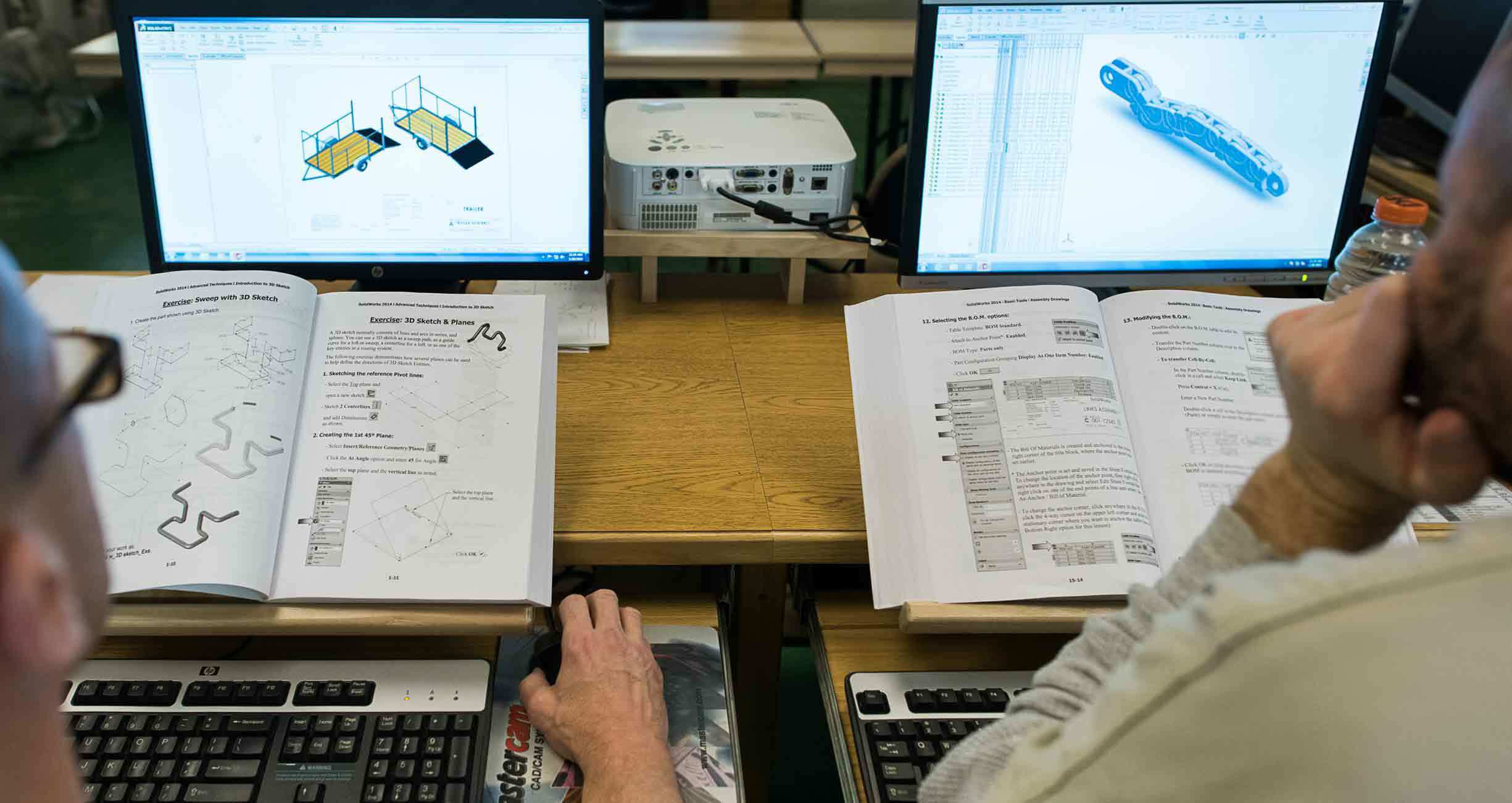

But her experience in classrooms on Spring Arbor University’s campus in Michigan now is vastly different from where she was when she started college. In 2017, Henry received an associate degree in general studies from Jackson College while incarcerated at Women's Huron Valley Correctional Facility in Pittsfield Township, Michigan. By the time she completed her sentence in 2020, she’d already received two more associate degrees, one in arts and applied science and another in business administration.

“I took all the classes I could take and got all the degrees I could get,” Henry said. “I just absorbed every ounce of knowledge I could absorb while I was there.”

Henry is one of more than 9,000 students who have earned credentials through the Second Chance Pell Experimental Sites Initiative (SCP) since it launched in 2016. Through the program, the U.S. Department of Education has provided need-based financial aid in the form of Pell Grants to students in state and federal prisons. Vera provides technical assistance to the participating colleges and corrections departments.

That financial aid is a critical resource for incarcerated students. Because without it, many, like Henry, would not be able to afford postsecondary education while in prison.

Research underscores the value of providing higher education opportunities for people in prison—and its benefits extend to others. Postsecondary education programs help reduce violence behind bars, leading to safer conditions for staff and incarcerated people. And people who pursue these educational opportunities are also better positioned to secure well-paying jobs when they return home, which benefits families and communities.

Providing postsecondary education in prison is an investment in public safety. People who have participated in these programs have 48 percent lower odds of returning to prison than those who have not. The RAND Corporation estimates that every dollar invested in prison-based education saves taxpayers five dollars from reduced incarceration costs. Lower reincarceration rates can cut the cost of state prison spending nationally by hundreds of millions of dollars every year.

And yet, this access to education has been fraught for decades. The 1994 Crime Bill banned Pell Grants for incarcerated people, making it impossible for them to be granted need-based financial aid in the two decades before SCP’s launch. After a campaign by Vera and a coalition of partners, Congress lifted the ban in 2020, and the new law takes effect in July of 2023.

For the first time in nearly three decades, all academically eligible incarcerated people—regardless of sentence length or offense—will soon be able to apply for federal aid for the 2023-2024 academic year.

It will be a hallmark moment for advocates and incarcerated people alike. The success of SCP underscores the impact that this access will have. In five years, SCP has enabled more than 28,000 students to enroll in college, and we are optimistic that that number will increase. After full reinstatement, we estimate 760,000 people will be eligible to receive financial aid in the form of Pell Grants for postsecondary education.

Earlier this summer, the Department of Education released its proposed regulations for Pell reinstatement. Colleges that want to offer postsecondary programs can learn about best practices by connecting with SCP sites and should reach out to their state’s corrections department if they are interested in starting a college-in-prison program. Vera’s First Class report also offers guidelines for starting a postsecondary education program in prison. Colleges, corrections departments, accreditation agencies, and the Department of Education all have a role to play in expanding access and ensuring all programs offered are high-quality and help incarcerated students to thrive—within prison walls and beyond them.

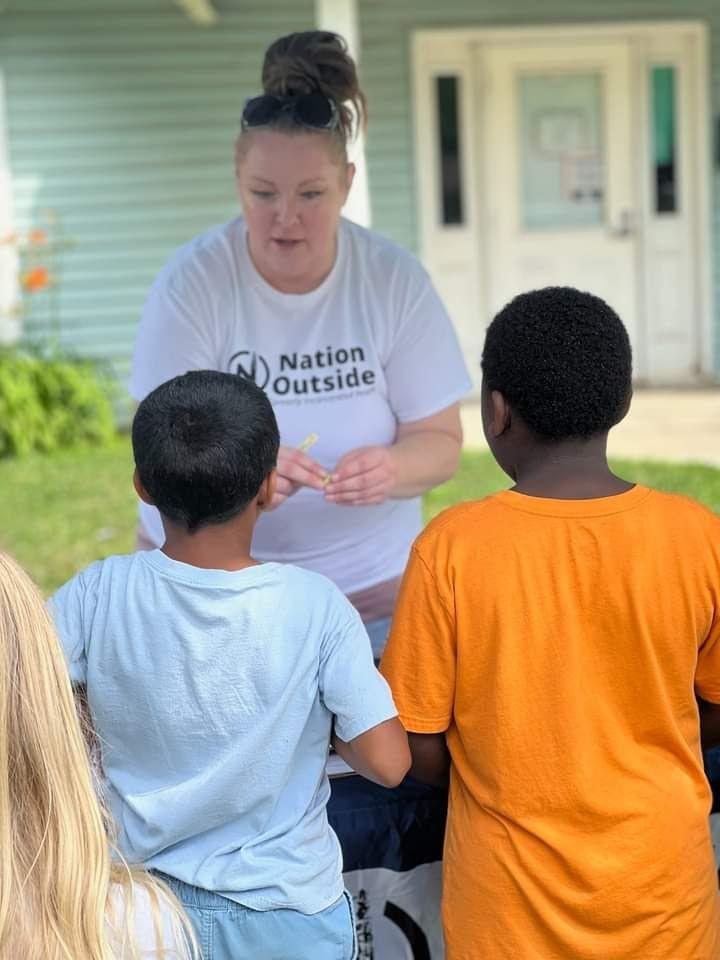

These days, while pursuing her bachelor’s degree, Henry volunteers with Nation Outside, a grassroots organization in Michigan that pushes for fair access to housing, employment, and voting for people involved with the criminal legal system. She also mentors formerly incarcerated people and young adults who were in foster care and serves as a residential manager at SOAR Café and Farms, a nonprofit that serves women survivors of human trafficking, sexual abuse, and trauma. Next year, she will begin pursuing a master’s degree in social work.

“Everything I’m doing is something I love,” Henry said. “I had been through so many things in my life—juvenile delinquency, foster care, teen pregnancy, addiction, rehab, therapy, prison, jail, probation, parole. And I’m like, ‘Why did I go through all this?’ And now I know why. It’s because I can help those who are struggling or going through similar things . . . to make changes one step at a time.”