More Police Won’t Make Public Transit Safer. Housing and Social Services Will.

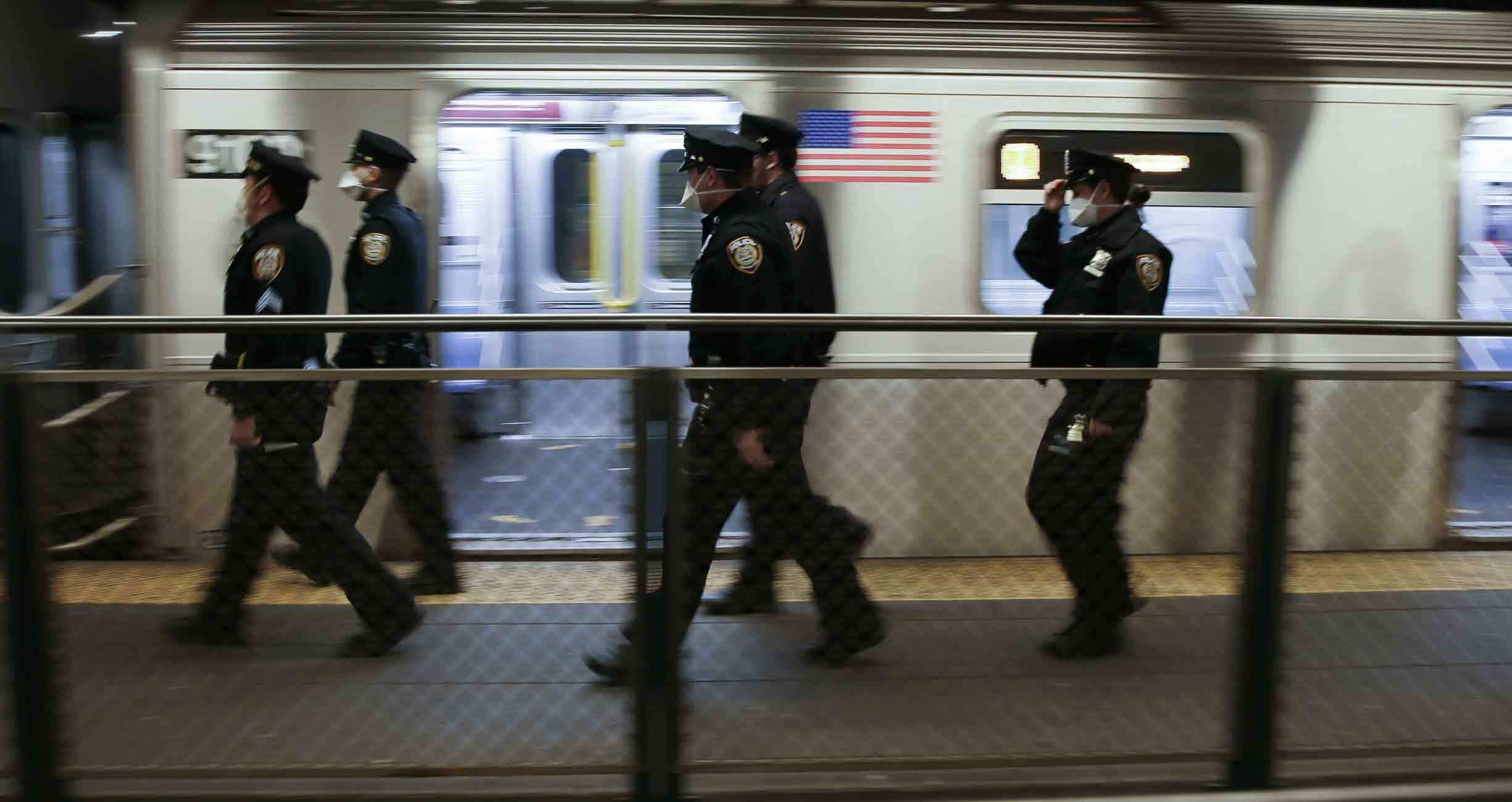

After a spate of high-profile violent incidents on New York City’s subway system, Mayor Eric Adams pledged to create police “omnipresence” on the subway. Since he took office in January, the new mayor has deployed 500 officers across the system, bringing the total number of police on public transit to a record 3,500.

Adams is responding to a perception—inflamed by tabloid news—that the subway is in crisis. The truth is more complicated: transit complaints on the subway are down nearly 28 percent since 2019, but crime per rider has increased as ridership has only rebounded to around 60 percent of pre-pandemic levels. There was one felony per million riders in 2019, compared to 1.63 in 2021. Still, with daily ridership of over 3 million in late 2021, the chance of being victimized is small, and the subway represents the city’s safest form of transportation.

Building public safety and increasing ridership on transit systems are important goals. Polls show that fear of crime is a leading reason people are hesitant to ride the subway. But polls also demonstrate that New Yorkers do not view hiring more police as the best public safety investment. Building more affordable housing and sending mental health responders in lieu of police ranked as higher public safety priorities this past spring.

New Yorkers are right: police omnipresence is not the most effective way to reduce violent crime nor does it address housing instability or substance use. Police deployment underground is also not driven by data. In 2020, 10 percent of New York City’s police force was patrolling the subway even though just 2 percent of crime occurred there. Pouring police into areas with relatively little crime leads to police over-enforcing what they encounter: trivial infractions like fare evasion, vendor licensing, or public sleeping. Adams ordered officers to prioritize making arrests for these so-called “quality of life” infractions and trumpeted a 51 percent increase in fare evasion arrests. That kind of “broken windows”-style policing fails to prevent acts of violence that jeopardize public safety.

Recent history illustrates this failure. From December 2019 to the end of 2020, former New York governor Andrew Cuomo flooded the public transit system with police, instructing them to crack down on fare evasion and homelessness. Cuomo’s attempt to police his way out of the city’s housing crisis failed. Costs for police overtime soared 21 percent, and unhoused populations in the MTA’s busiest stations surged 45 percent last summer. NYPD practices on the subway sparked allegations of racism and an investigation by the state attorney general’s office. And the largest police presence on the MTA in a quarter century coincided with growing public safety concerns underground.

But politicians like Adams insist that more police and unproven security technology are the only ways to improve public transit. That is simply not true. Instead, officials can implement a host of popular and more effective options to reckon with the slight rise in crime on public transit, build public safety, alleviate housing instability, and increase ridership. These include:

- Providing housing, not police. Unhoused people often choose to sleep in public transit rather than shelters because of the dangerous conditions in the shelter system; dangers that were only exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In New York City, the solution lies in filling the 2,500 city-funded apartments currently sitting vacant due to what advocates call a “bureaucratic nightmare,” and providing more safe, single-unit accommodations.

- Investing in outreach. Rather than hiring police to criminalize homelessness and mental health crises, New York City should expand social service support systems. A TransitCenter report from last year recommended that New York City deploy fewer cops and more unarmed, non-police personnel like outreach workers. That tactic has been implemented in other jurisdictions: Los Angeles County recently hired 40 social workers to conduct outreach on the Metro. LA has also contracted with People Assisting the Homeless (PATH) to provide services outreach for unhoused people, and evaluations show that PATH teams are more cost effective than police officers at providing services to unhoused people.

- Improving infrastructure. Infrastructure improvements also help. The Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) Pit Stop program provides public bathrooms with attendants, which reduced reports of urination, defecation, graffiti, and needles in station elevators by 98 percent.

- Expanding fare justice programs. In 2019, New York City spent $249 million on additional police—which only prevented $200 million in fare evasion losses, for a huge net loss. Not only are police more expensive than their impact on fare evasion, they also impose enormously unequal costs on Black people and other people of color, who are the subjects of 90 percent of fare arrests. Instead of attacking the symptom of fare-beating, New York City should address the two things that drive it: poverty and inconvenience. For instance, safety improved when Kansas City implemented a zero-fare program in 2020, with security incidents declining by 17 percent per 100,000 riders.

Taken together, these measures can help address housing instability and mental illness while also increasing ridership. More riders are critical, experts say, as empty stations and trains lead to more crime.

Our public safety toolbox has more to offer than billions of dollars for bloated police budgets that saturate subways with police, particularly when their presence on public transit is already at record highs and clearly not effective. It is past time that officials turn to evidence-based solutions instead of pouring yet more resources into failed policy.