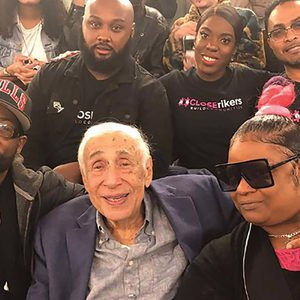

In Memoriam: Herb Sturz, A Modest Giant Among Advocates

Herb Sturz, a social justice legend who devoted his life to public service and who served as Vera’s leader from its founding in 1961 through 1978, passed away on Thursday morning. He was 90 years old.

Herb was a modest giant among advocates. His work touched countless lives, and his mobilization led to some of the most important criminal justice reform movements of our time—from the curtailment of stop and frisk to the push to close New York City’s formidable Rikers Island jail complex—but many have never heard his name. He was inconspicuous about working behind the scenes to better the lives of others. Although he has been the recipient of dozens of honors and sat on the boards of countless organizations, for Herb it was never about popularity or recognition. It was about the humanity in all of us. The child of immigrants who came through Ellis Island, he was a classic New Jersey native with a dry sense of humor.

When Herb founded the Vera Institute of Justice—then called the Vera Foundation—with Louis Schweitzer in 1961 and, at 30 years old, became its first executive director, he set his sights on ending New York City’s overreliance on cash bail. More than 60 years later, his advocacy and commitment has led to the creation of dozens of organizations dedicated to helping millions of people both locally and around the world. Because of Herb and Vera, the Addiction Research Treatment Corporation, Safe Horizon, the Legal Action Center, Mobilization for Youth Legal Services, Pioneer Messenger Corporation, Wildcat Service Corporation, the Neighborhood Youth Diversion Corporation, the Manhattan Court Employment Project, La Bodega de la Familia, the Harlem Defender Service, the Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services, the Center for Employment Opportunities, the City Volunteer Corps, the Midtown Community Court, Red Hook Community Justice Center, the Center for Court Innovation, the After-School Corporation, and the Center for New York City Neighborhoods—just to name a few—were born. Among other projects, Herb’s advocacy also helped to launch Easyride, the forerunner of Access-A-Ride, to provide transportation to the elderly and people with disabilities in New York City.

“They are not Vera’s children,” Herb’s friend Jack Rosenthal said in Sam Roberts's 2009 biography, A Kind of Genius: Herb Sturz and Society's Toughest Problems. “They’re Herb’s children.”

Today, Vera—arguably the most sweeping of Herb’s achievements—is headquartered in Brooklyn and has offices in Los Angeles, New Orleans, and Washington, DC. The organization has worked on hundreds of projects both nationally and abroad to shrink and transform the criminal legal system and to this day advocates to end injustices, including cash bail, that continue to harm millions.

Herb and Louis’s original undertaking, dubbed the Manhattan Bail Project, was the first meaningful criminal legal system reform program the country had ever seen. Herb knew that no one should have to buy their way to freedom, and his efforts showed others the same. The project was replicated in dozens of cities across the country and ultimately led to the landmark National Bail Reform Act of 1966.

On December 31, 1977—Herb’s 47th birthday—New York City Mayor-elect Ed Koch called Herb at home to offer him a job as deputy mayor for criminal justice. While in his new role, he continued to pioneer efforts to close Rikers, recognizing the toll of mass incarceration and the need to invest resources in services that would benefit communities.

As the chairman of the City Planning Commission, Herb developed a number of neighborhood planning initiatives, including an Arson Strike Force, which sought to combat the epidemic of fires ravaging tenements in low-income neighborhoods. Later, he worked on reentry programs like Single Stop, which ensures that incarcerated people get access to the federal and state benefits they are owed, and served on the editorial board of the New York Times. In its pages, he advocated for expanding Medicare and other social reforms.

Herb was a listener. He spent time with people incarcerated on Rikers Island and advocated for what they actually needed—aid and access to employment, education, and housing—to keep them out of the system. Even in his last few years, he continued to attend monthly meetings to close Rikers, leading to the historic city council vote in 2019 to do just that.

A lover of poetry, his life was the embodiment of one of his favorite lines, from “The Summer Day” by Mary Oliver: “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

Herb Sturz has left an incredible, lasting, and meaningful legacy. He will be remembered for his devotion to others, and will be missed by the many he mentored at Vera and those whose lives were forever changed by his work.