"The Box": How The Conviction History Question Shapes College Admissions

Syrita Steib knew she was an unequivocally strong applicant. “I had a 3.875 GPA. I had 30 college credits. I literally had two Bs on my transcript,” she said. Yet, just one day after submitting her application, the University of New Orleans (UNO) issued its decision, rejecting her.

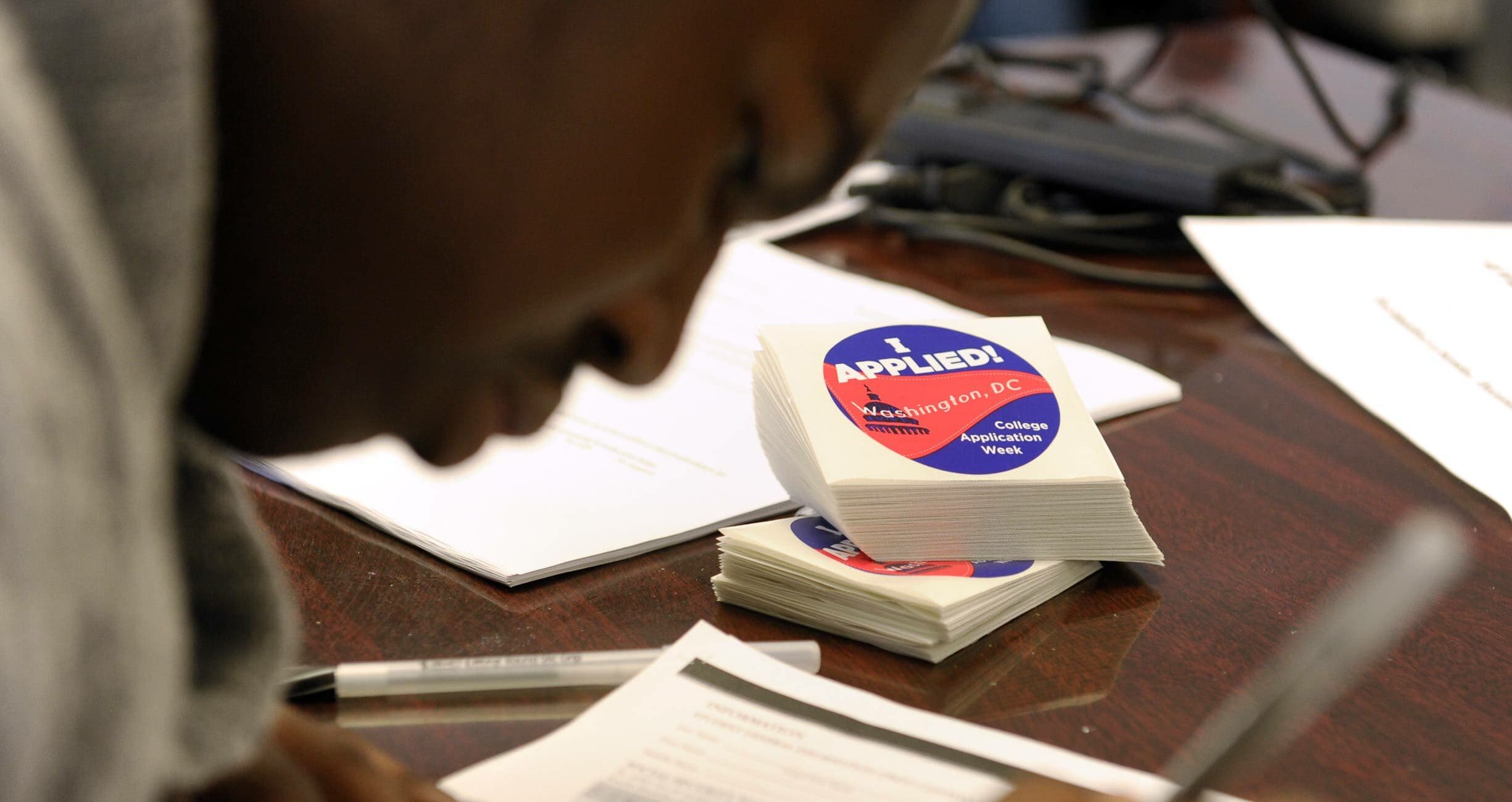

Steib immediately suspected the reason why: she’d checked yes on “the box.” Approximately 70 percent of four-year colleges in the United States require that applicants disclose prior experience with the criminal legal system, a practice that has far-reaching implications for system-involved people like Steib. Even more, the box represents another insidious example of the collateral consequences of system involvement and how people with conviction histories are thwarted from participating fully in society.

The imminent restoration of Pell Grant eligibility for people in prison marks a major stride forward in making higher education more accessible, but the box remains an obstacle for many people to get a college education.

In response, over the past several years, some states have passed laws to “ban the box,” barring postsecondary institutions from asking applicants about most conviction histories. Moreover, the Common Application—the most widely used undergraduate universal application in the country—eliminated the box in 2019, recognizing its commitment to “advancing access, equity, and integrity in the college admission process.” Yet, the criminal background question endures on most institutions' individual applications, even as many profess their dedication to diversity and inclusion. And, frustratingly, to justify the persistence of the box, many schools falsely cite campus and public safety.

The growth of prison education programs (PEPs) and the victory of Pell Grant reinstatement are significant. Still, higher education can better welcome and foster the success of system-impacted people, whether they pursue college while incarcerated or after they’ve served their sentence. Banning the box is critical to ensuring that the one in three adults with a history of criminal legal system involvement can pursue their educational goals.

“The box” deters potential applicants

Steib keenly recalled her shock and indignation when she was initially rejected by UNO. “When I was sentenced, the judge said I had to do this, this, this, and then I would get my life back. They didn't tell me that I was going to be denied a right to safe housing, that I would be denied an education, that I would be denied every constitutional right,” Steib said. “Yeah, you'll get out of prison in 10 years, but this is really like a life sentence. They didn't say that.” She applied to UNO again, this time not checking the box—and was admitted. She matriculated and earned her bachelor’s degree elsewhere before channeling her experience into her advocacy.

Although Steib was not dissuaded by her first admission denial, the demoralization she felt is widespread and symptomatic. As indicated by the Education from the Inside Out Coalition’s finding that nearly two in three applicants who checked “yes” on the felony conviction history question ultimately did not submit their application to the State University of New York (SUNY), many prospective students are, from the onset, deterred. One study estimated that immediate college enrollment rates were reduced by 12 to 22 percentage points for high school graduates with a recent drug conviction after the introduction of the drug conviction question on the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) form. Fortunately, however, as part of the FAFSA Simplification Act, due to take effect this July, the drug conviction question will be removed, eliminating one barrier faced by prospective students.

The false narrative of public and campus safety

Research demonstrates that there is no significant difference between the campus crime rates of institutions that probe undergraduate applicants’ criminal backgrounds and institutions that do not. Yet, many schools—even those that maintain their commitment to recruiting diverse student bodies—invoke public safety as the primary reason for preserving the box on their applications.

People of color are disproportionately targeted by the criminal legal system. Black people, for example, are more likely to be stopped by police, detained pretrial, charged with more serious crimes, and sentenced more harshly than white people. The prospective students most likely to be impacted by criminal background disclosures, therefore, are students of color. Refusing to ban the box undermines many institutions’ stated mission to cultivate campus diversity.

The campus and public safety narrative also undermines the idea that after completing their sentences, be it on probation or in a correctional facility, people should be able to move on with their lives. This illusion is especially characterized by people like Jay Marshall. Despite being decades removed from his probation period, Marshall was confronted by the conviction history question on his graduate school application. Put off by the insinuation that he could not be trusted, Marshall never applied.

The ongoing movement to ban the box

Today, Steib is the founder and executive director of Operation Restoration, a New Orleans organization that aids system-involved women and girls in restoring their lives and realizing their full potential through services and programming in addition to advocacy. In 2017, Steib helped craft and pass ACT 276—making Louisiana the first state to ban the box in public college admissions.

Several states have enacted laws similar to Louisiana’s ACT 276—including Maryland, Washington, Virginia, and Delaware—and more states have proposed or pending legislation (Nebraska just introduced a bill to ban the box this past January). Notably, only California has moved to ban the box at both publicly funded and private institutions. On the federal level, under the Obama administration, the Department of Education (ED) urged schools to go beyond the box in 2016, and U.S. Senator Brian Schatz has introduced a bill to amend the Higher Education Act of 1965, which would encourage institutions to remove the box, though efforts have stalled.

In lieu of congressional action, the Biden administration’s ED is pushing for greater accessibility. An updated Beyond the Box report, released last week, offers colleges guidance on mitigating barriers to higher education and improving academic outcomes for system-involved people, which will be particularly relevant to colleges considering or planning to launch programs in prison once Pell eligibility is restored on July 1. While institutions administering PEPs won’t be required to amend their applications, regulations stipulate that they must ensure incarcerated students can “fully transfer their credits and continue their program” post-release. Banning the box is the natural next step for any institution committed to the education of system-impacted people, and which asserts its dedication to maintaining a diverse student body.

While anyone can, and should, push for their alma mater to reconsider its admissions practices, Steib views legislative action as the best course to ban the box. Change by individual institution—rather than by state or federal decree—means that it remains at the administration’s will and relies on external pressure and momentum that can be fleeting. Implementation is also inconsistent and varies by school, Steib says.

A fair chance

The campaign to ban the box in college admissions is part of a larger movement to prohibit inquiring about applicants’ involvement with the criminal legal system, particularly in the housing and labor markets—an endeavor to lessen the collateral consequences of system involvement and give people a fair chance at rebuilding their lives. At least 37 states and more than 150 cities nationwide have imposed housing- and work related ban the box measures.

Despite her discouraging experience with the college admissions process, Steib thrived as a student. Indeed, she recalls a professor's incredulousness when she disclosed her system involvement—and how she swiftly disabused them of the notion that her aptitude was exceptional. "Everybody in prison is just like me,” she told them. “There's some of the smartest, most ingenuitive, amazing, awesome people; they are responsible for who's standing in front of you today."