Care over Confinement: Kids Need Second Chances and Services to Succeed

On May 12, 2020, Molly made a heart-wrenching decision no parent wants to face—she approved a plea deal that took her 15-year-old son away from their family for two years of juvenile detention in Louisiana state custody. The alternative was having him tried as an adult, facing a sentence of 15 to 55 years in prison, for a fight he’d had with other teenagers.

“My back was against the wall. . . .I’m a single mom. I had no money for a lawyer. [The court] said if I wouldn’t [agree to] the plea, he’s gonna be trialed [sic] as an adult, 15 to 55 years,” Molly recalled. “I sat him down in the courtroom that day and said, ‘This is what I gotta do. I have to save your life. You have to go into custody.’”

But Molly’s son didn’t understand his own situation. “Mom, where am I? I don’t want to be here,” was a constant refrain during his phone calls home. “That’s the worst a parent could ever experience,” Molly said. “Not knowing what to say to your child. . . I didn’t sleep at night.”

Molly and her son are not alone. As of October 2020, more than 25,000 young people were detained in juvenile facilities across the United States, and Louisiana’s Office of Juvenile Justice (OJJ) held 434 children in secure custody in the first quarter of 2023.

The experience of being arrested and going to court itself can exacerbate underlying trauma and drive people to re-engage in the behavior that initially led to their court involvement. For youth who experience detention or are otherwise removed from their homes, the harms are further compounded. Their parents and families also face complex emotional and psychological impacts. Involved parents like Molly often experience the pain of exclusion from the decisions that shape their children’s lives once the juvenile legal system steps in.

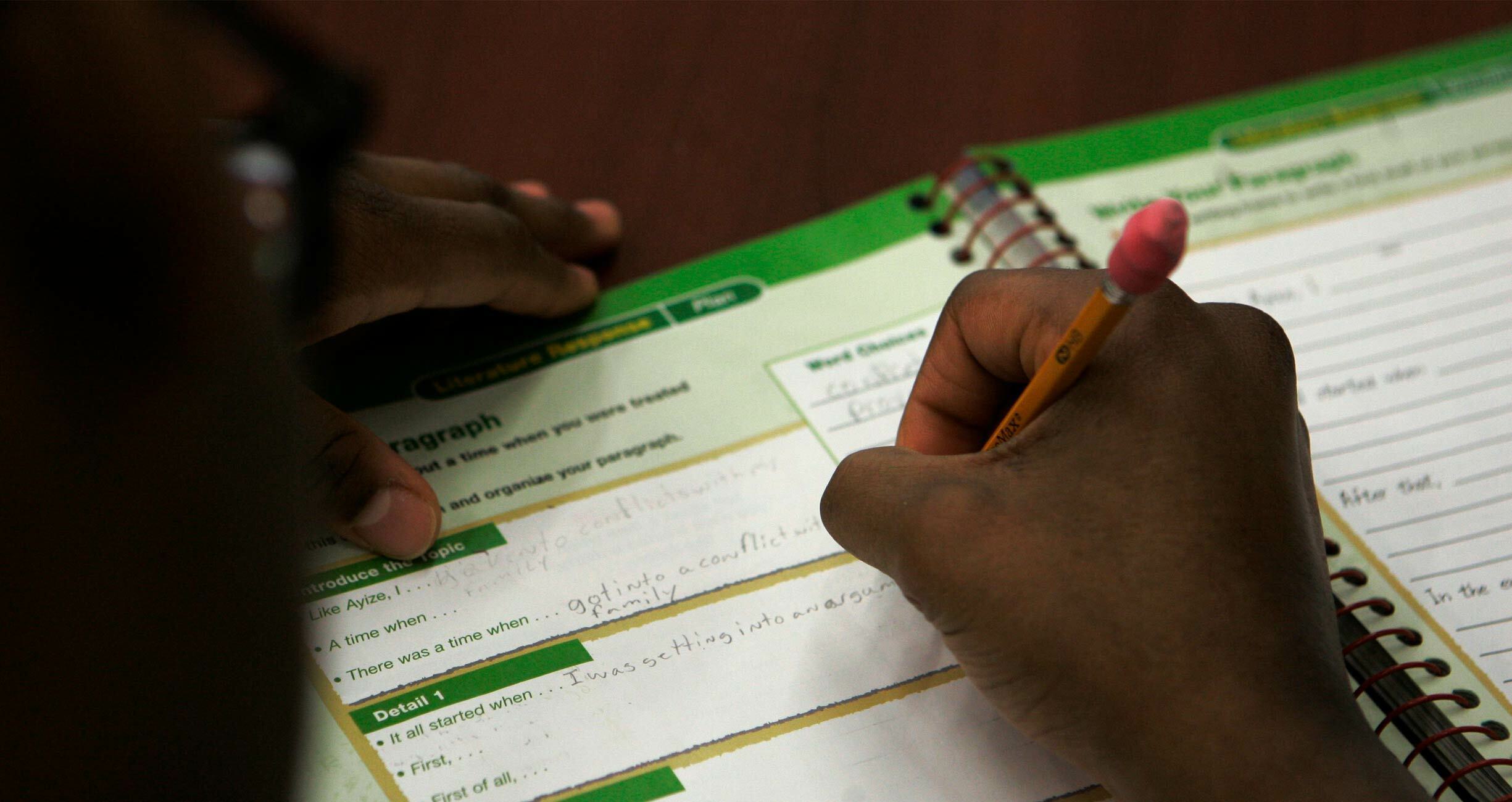

Molly knew what her son needed when he got in trouble: healing, counseling, and anger management. And she was ready to provide it: “I had all his services lined up, medical card, everything he needed.” What she didn’t know was that her son was not going to be cared for or offered any services while he was in state custody. Not going to school, not getting mental health treatment, and—for the first six months of his confinement—not being let out of his cell for more than 15 minutes a day.

The conditions at his first facility were so horrific, Molly’s son didn’t even want to tell her about his living situation. “I found out about it on the news. . . it was [the] Marshall Project,” she recalled. When she questioned her son about his own circumstances after reading the article, she learned he’d once been left to sleep on the floor of a flooded cell, he had been told to drink from the toilet when he asked a staff member for water, and that kids were sleeping on iron beds, sometimes with feces in their living spaces. Her son also shared with her that he’d been slapped by a staff member, which led to a physical altercation resulting in an additional charge that added more time to his term of confinement. “He had no one he could turn to while experiencing all these things in his own mind with no guidance. . . . He didn’t have access to anything. . . . They violated his constitutional rights,” Molly explained.

The injustices her son faced in confinement only made it harder for Molly to accept his OJJ placement. In Louisiana, parents can be threatened with legal action if their child doesn’t attend school regularly, but the juvenile legal system isn’t held to the same standard. “If my kid is not going to school five days [a week in my care], I'm being sent to the district attorney's office. And here it is, they're not going to school at all, and that's [a result of] the judge's order,” Molly said. “Why can’t I have my kid back and start these services and give him the rehabilitation that he needs?”

Families & Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children (FFLIC), a statewide nonprofit organization working to keep Louisiana’s kids out of incarcerated settings, reports that 40 percent of incarcerated children in Louisiana have mental health challenges that are not best addressed in detention facilities. Molly’s son is one of them.

“I feel like the system created my son to be so angry, without mental health [services]. He was traumatized by past events that happened there at their facilities . . . . when things would happen there, he didn't know how to act because he wasn’t getting the [treatment] he needed.”

Incarceration itself doesn’t help children. Molly believes the system is harsh on youth who find themselves in legal trouble, “just seeing their wrongdoing” and “giving them so much time [in detention]” when they need opportunities for growth and change—and the resources to support them. “I feel like every kid deserves a second chance,” Molly explained. “No kid is perfect. . . .Why can’t you look at that kid and say, ‘He deserves a second chance [before being placed in custody]?’”

U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) Administrator Liz Ryan, formerly of the Youth First Initiative, echoes FFLIC and Molly’s sentiments favoring treatment and second chances for youth. In a 2022 OJJ article introducing the Youth and Family Partnership Working Group, Ryan described her goals as OJJDP administrator as “treating kids as kids”; “serving them at home, with their families and in their communities”; and “opening opportunities” for youth who come into contact with the juvenile legal system.

Ryan’s goal to keep kids out of detention facilities and with their families is well supported by the public—more than 75 percent of people support treatment services over incarceration for youth and 84 percent agree that families should be involved in designing the services. Defaulting to community-based resources that have been proven to work would be especially beneficial to the thousands of currently separated families like Molly’s.

In the roughly three years he’s been incarcerated, Molly’s son has never been granted a home pass—an authorized family visit away from the detention center. Molly reported the state conducted a home visit and she passed, but when her son applied for a furlough, it was denied without explanation. The family separation is especially difficult for the two younger children Molly still has at home. They miss their older brother and ask Molly frequently about when he is going to return: “They get emotional. . . .They [are] very worried. They miss him. They love him.”

The children have been to visit on occasion, but Molly’s son has been moved to two different facilities since entering OJJ custody and is now a three-and-a-half hour drive from their home. “I just don’t like taking them there to see [their] brother in that situation.”

Molly doesn’t believe being in confinement is helping her son but maintains hope for his future. She wants him to go to the Youth Challenge Program, an alternative education program for students who want to change their futures, run by the Louisiana National Guard. “He needs counseling, anger management, and help to find him a good job.”

And as for the juvenile legal system, Molly says, “They need help. They need the services, they need teamwork. . . .show these kids like, ‘You do have a future.’ . . . People need to understand these kids are really going through it in here.”