California’s New Workplace Heat Standards Don’t Apply to Prisons, Reflecting Harmful Neglect Across the United States

Forcing incarcerated people to endure dangerously high temperatures does not make anyone safer.

When California’s workplace safety board created important indoor heat protections for workers earlier this year, the policy exempted prisons. California’s governor cited cost concerns, but this unjust exclusion was facilitated by the sadly pervasive perception that people who live and work in prisons deserve tortuous conditions. In Louisiana, when trying to persuade voters in Jefferson Davis Parish to fund a new jail, local leaders proudly touted that the facility would not include air conditioning.

Twenty-two states don’t place official limits on tolerable heat for jails and prisons. As a result, every summer, incarcerated people like Adrienne Boulware suffer and die due to extreme heat.

Boulware, a mother of four and grandmother of 11, was set to come home from Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF) in 2025. On July 4, Boulware was forced to wait in line for medication in the midday Central Valley sun for 15 minutes as temperatures soared past 111 degrees. Once she reentered the facility—which lacks air conditioning—she was overcome by heat exhaustion. She died two days later.

Boulware’s death is a consequence of decisions made by California to disregard the safety of incarcerated people.

“Something could have been done to prevent [her death],” Boulware’s daughter told the Sacramento Bee. “And she was so close to coming home.”

Neglecting the safety of people in prison does not create public safety. As climate change brings more severe extreme heat to prisons and jails, the people inside deserve much better protection.

Jeopardizing the health and safety of people who live and work in prisons

The aging infrastructure of most carceral facilities was not designed to keep the people working and living within them cool in the face of rising annual temperatures. The heavy concrete used to build the walls and cells in many prisons absorbs heat. Too many prisons also fail to provide clean water to incarcerated people, a necessity in extreme temperatures. And many California prisons are located in rural areas, far from hospitals that can help people who fall ill from heat stroke.

Though people who work in prisons can go home to clean water and air conditioning, keeping prisons dangerously hot also harms corrections staff. Corrections staff already face much higher rates of injury and illness than other workers, in addition to higher rates of suicide. Researchers warn climate change may make working in uncooled prisons so unbearable that recruitment will suffer, leading to understaffing that can further endanger incarcerated people.

The health of incarcerated people is already jeopardized by the stressful conditions they endure while in prisons and jails. People in prison are more likely to have chronic health conditions like diabetes and heart disease, which make them more vulnerable to heat-related illness.

A 2023 report from the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights (EBCHR) found that eight state prisons in California are vulnerable to extreme heat, defined as days with temperatures above 103 degrees.

“The problem with [being] locked down inside of a cell that's extremely hot is that [. . .] you literally can barely go to sleep because literally, the wall is sweating,” said Noire Wilson, a respondent in the EBCHR report. “It was like we were inside of an oven, just cooking. Just constantly cooking.”

As climate change advances, suffering in such spaces will only increase. The EBCHR report recommends reducing the size of the incarcerated population, with a focus on releasing people 50 years or older and those who are most vulnerable to heat exposure. It also recommends that California close the prisons most vulnerable to heat hazards.

The fight to save lives

In the wake of Boulware’s death, the California Coalition for Women Prisoners (CCWP) has called for “immediate implementation of basic lifesaving heat protocols in all of California’s prisons, including continual access to ice and air-conditioned spaces, no lockdowns in overheated cells, [and] regular checkups by medical personnel on medically vulnerable people.”

“I know what it feels like to be so dehydrated that you can’t see,” said Elizabeth Nomura, who was formerly incarcerated in CCWF. “[People in CCWF] are sitting in a room toasting in what feels like an oven. They’re all suffering.” She is now a state membership organizer for CCWP.

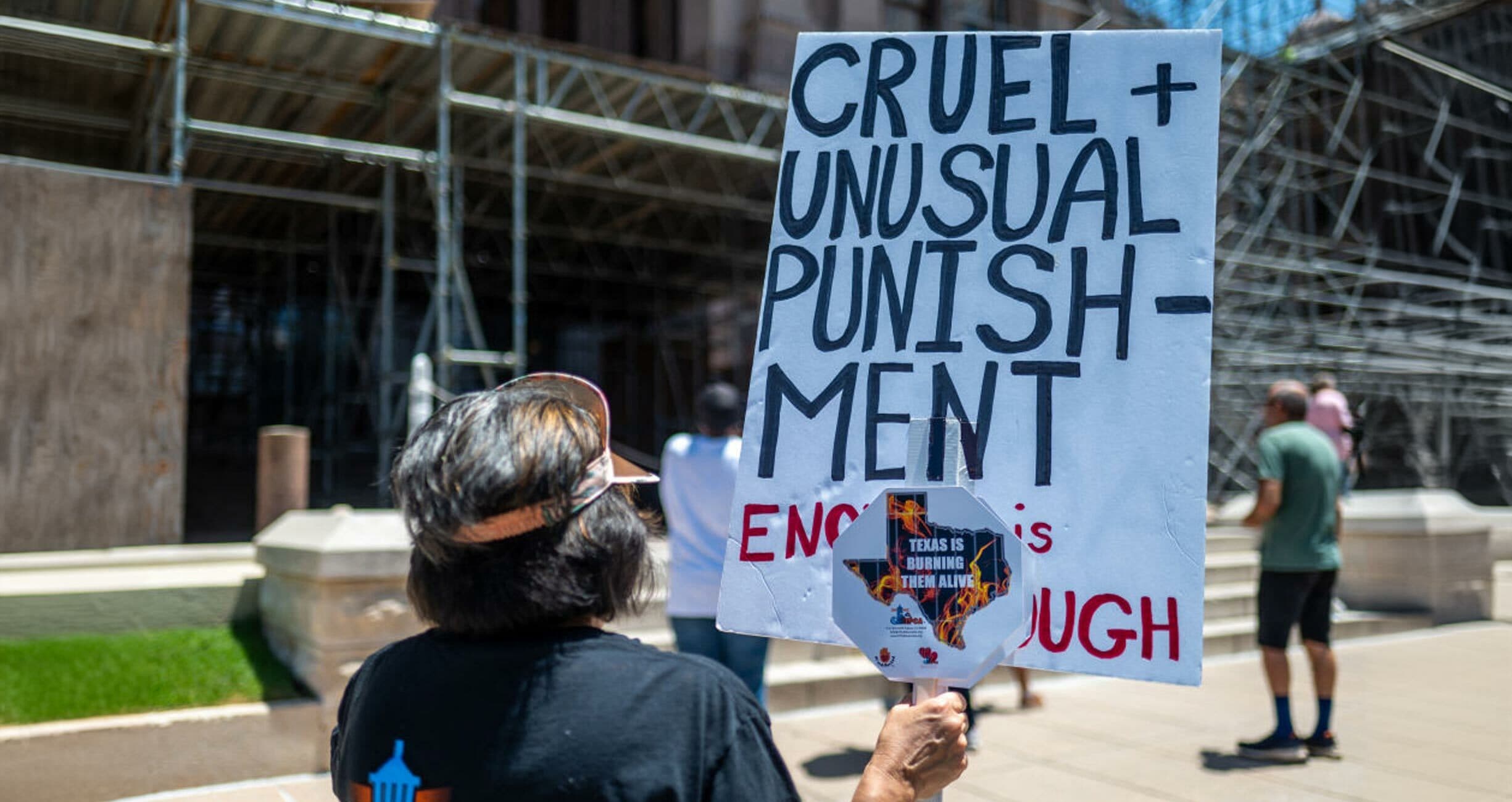

Advocates in other states are also working to prevent heat-related deaths in prisons. After at least 41 people died in Texas prisons during last summer’s heat wave—of either heart-related or from unknown causes that advocates and family members believe were triggered by heat exposure—nonprofit organizations have joined a lawsuit filed against the state in federal court. The case was originally brought by Bernie Tiede, whose life was endangered while he was housed in a facility where cell temperatures were known to reach 110 degrees. Lawyers argue that keeping people confined in stifling heat is unconstitutional and are asking that prisons be kept at temperatures under 85 degrees.

Federal legislators also introduced a bill this summer that would protect people in prisons nationwide. In July, Senator Ed Markey and Representative Ayanna Pressley introduced the Environmental Health in Prisons Act. This legislation would seek to improve the environmental health of both incarcerated people and people who work in federal prisons by directing the Federal Bureau of Prisons and related agencies to publish data on environmental stressors in their facilities, including temperature. It would also create a $250 million grant program to address environmental health harms in prisons.

As climate change advances, future summers will continue to bring life-threatening heat. Forcing people to endure these dangerously high temperatures—while confined in metal and concrete and with no way to keep cool—is inhumane and does nothing to advance public safety. The United States incarcerates far too many people when there are far better alternatives. Decreasing the number of people who are trapped in dangerously hot prisons is imperative.