Black Leaders Who Used the Law to Reform Prisons from Within

Effecting change from within the brutal, racist, and dehumanizing confines of U.S. prisons has long been a dangerous and difficult endeavor. Black people, already overrepresented in prison systems across the country as a result of racism at every stage of the criminal legal system, endure harsher punishment once incarcerated. As we celebrate Black History Month, it is worth also celebrating the stories of Black incarcerated people whose fight for human rights helped improve prison conditions for people of all races.

For much of U.S. history, incarcerated people were denied protection under the Constitution. In 1871, the Virginia Supreme Court declared that a person who had been convicted of crimes forfeited all rights: “He is for the time being the slave of the state.”

As a result, courts dismissed lawsuits from incarcerated people who complained of degrading mistreatment, saying that they deserved no protection under the law. But the persistence of people who had experienced prison and were inspired by the successes of the Civil Rights Movement refused to accept this denial of basic rights, working to effect change during the 1960s and 1970s.

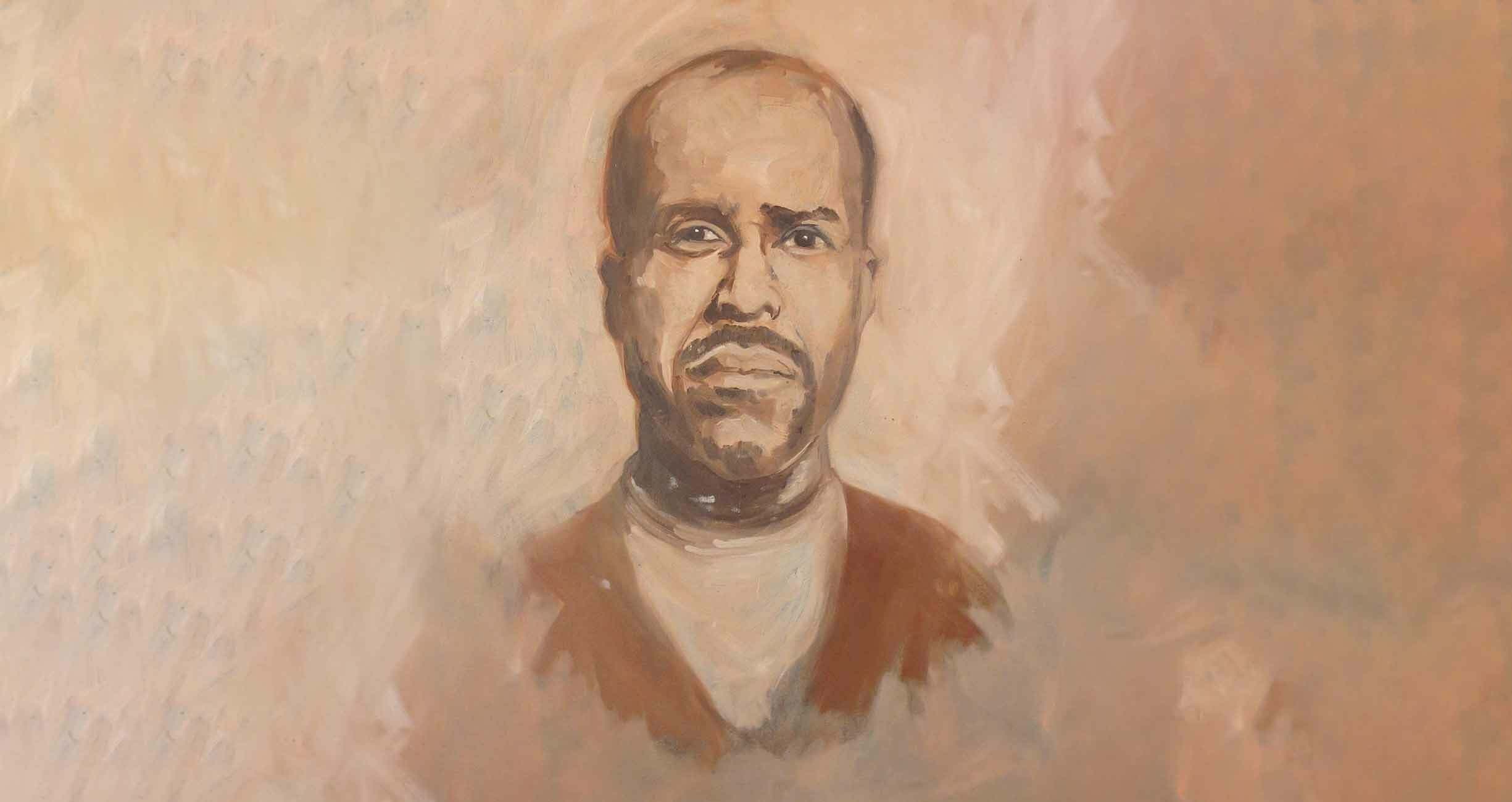

Martin Sostre, for example, grew up in Harlem and was incarcerated after a 1952 arrest. While behind bars, Sostre undertook a course of self-education. “For the first time, I had a chance to think, and began reading everything I could—history, philosophy, and law,” he told writer Arthur Dobrin. He began learning about Islam in “Little Siberia,” as the frigid prison yard at Clinton Correctional Facility in upstate New York was dubbed, and sought his own copy of the Koran. Sostre also requested visits from Black Muslim ministers, as incarcerated Christian people had been granted time with their faith leaders.

His requests were met with scorn, however, and he was placed in solitary confinement for causing trouble in the prison. This meant sleeping on a concrete floor with no bed, mattress, lights, running water, or toilet.

From these awful circumstances, he put his studies of the Constitution and constitutional law to use. Sostre filed a lawsuit against the warden of his prison for denying him the ability to obtain a copy of the Koran, claiming that this infringed on his right to practice his religion, as guaranteed by the First Amendment. The suit was successful, laying the groundwork for others, including the landmark 1964 Cooper v. Pate decision by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Thomas Cooper, a member of the Nation of Islam, brought a lawsuit against the warden of the Illinois prison where he was incarcerated because the warden would not allow him to purchase religious publications by Black Muslims or to obtain a copy of the Koran. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Cooper, establishing the precedent that the Bill of Rights applied inside of prisons and that incarcerated people had the right to protection under the Civil Rights Act of 1871.

This ruling gave incarcerated people the right to challenge the conditions that they were forced to live in, and an ensuing wave of lawsuits pushed prisons around the country to change their operations. Sostre later sued to protest mail censorship, dehumanizing physical examinations, and solitary confinement. He inspired other “jailhouse lawyers” to fight for their rights and, in at least one case, gain freedom from prison. One lawsuit Sostre filed, after being left in solitary confinement for over a year for practicing law behind bars, led the Honorable Constance Baker Motley of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York to state that “basic constitutional rights cannot be sacrificed, even in the case of prisoners.”

Lawsuits, combined with strikes, collective action, and uprisings like the Attica Rebellion, drew worldwide attention to the brutal prison conditions in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. As a result of the collective efforts of countless people, legal racial segregation in prisons ended and incarcerated people won some important protections, including the right to practice their religion and seek redress for grievances in court. While we honor these hard-won victories, we also recognize that nearly 2 million people remain incarcerated in fundamentally brutal, inhumane jails and prisons that don’t advance justice, nor actually deliver public safety.

As we work to end mass incarceration, we need to support incarcerated people who continue to fight to improve prison conditions from the inside. As Martin Sostre told the New York Times in 1975, “People say prisoner’s rights, but human rights are human rights.”