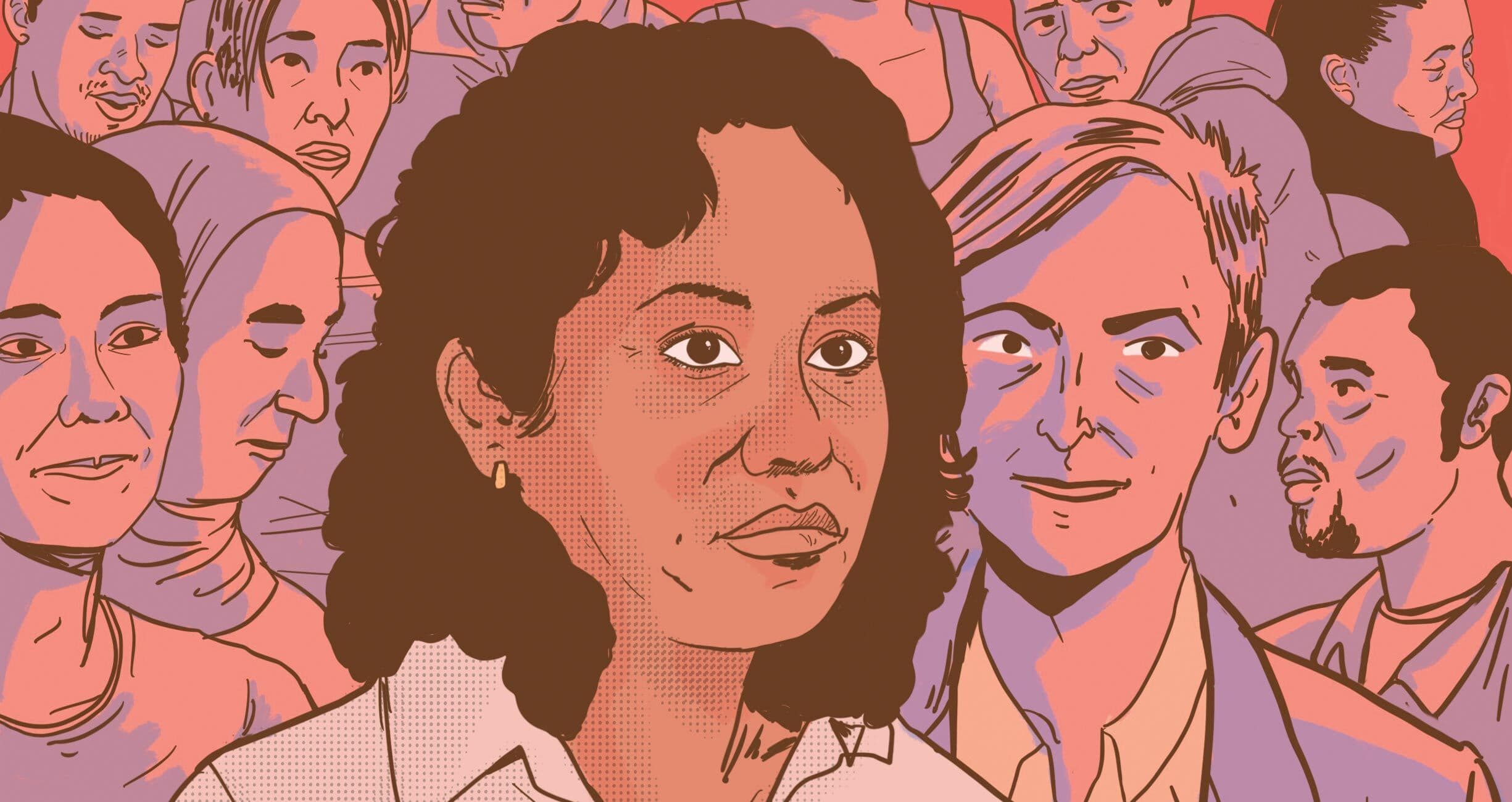

10 Stories from Immigrants Seeking Safety in the United States

“We are human beings. Even though we are in another country, we are human beings.”

Each of the 46 million people who have immigrated to the United States brings a unique story. Some come seeking safety and opportunity. Others come for education or to be with family. Yet the U.S. has failed to align its immigration laws and practices with 21st century realities, leaving a system that harms far too many. Too often, immigrants are talked about—rather than listened to.

These are the stories of 10 people who have experienced the U.S. immigration system firsthand. Some were able to fight for their rights with the assistance of publicly funded attorneys. Some were not. Their stories expose the inhumanity of the current system, the need for legal protections for more people, and their desire to live safely and with dignity.

Some names have been changed to protect subjects’ identities.

It is too important to have a lawyer. Their duty is to defend our rights because we are human beings. Even though we are in another country, we are human beings.

After escaping serious violence in Mexico, Raina and Ana came to the United States to seek asylum, as was their right under U.S. and international law. Yet when they encountered Border Patrol agents, they were imprisoned instead of aided. The women spent weeks locked up in one of the many jails that is part of the massive United States immigration detention system.

When you come here, you are looking to get away from danger. I felt devastated when we got to the jail. They take you in handcuffs; not just around your hands but also chains at your feet.

While held in detention, Raina and Ana were told to sign papers in English that they could not read. They later learned that they had signed documents giving up their right to seek asylum and, essentially, agreeing to be deported. Luckily, a representative from a publicly funded deportation defense program intervened so that both women could begin the process to establishing legal residency in the United States.

Read Raina and Ana's Story (en español)

If I could speak to the leaders of this country, I would say that we immigrants are in your hands. We are helping the country grow and be strong. It is in your hands to help us live a dignified life.

Rosita’s son’s father was deported to Guatemala when her son was only five years old. He was only allowed to say goodbye through glass at an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention center. Ten years later, he still had not been reunited with his father. Vera reviewed ICE reports to Congress and found that, between 2015 and 2020, the government ordered more than 156,000 parents of U.S.-born children be removed from the United States. Rosita believes an attorney might have been able to prevent his deportation and has called for systemic change to provide legal representation to all people facing deportation as a way of preventing the heart-wrenching separation that her family has been forced to endure.

When I was in the hielera, I was told about an officer that everyone was scared of because he would deport you. Two days in [CBP custody], he arrived and called for me. When I met him, he said, ‘Okay, you will do everything I tell you to or will be in trouble.’ He asked for my information and then told me I should sign a few documents. When I tried flipping the page so I could read what the document contained, he would flip it back and pointed to where I should sign. I couldn’t read what was in it, but I had to sign it, so I did.

When Sophia surrendered herself to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), she was first placed in the “perrera” or the “dog kennel,” the name many use to refer to CBP processing facilities because they are like cages made of chain-link fence. Then she spent two weeks in the “hieleras” or “freezers,” the name commonly used to describe CBP’s notoriously freezing holding cells. While there, she was coerced into signing a voluntary departure attestation that she could not even read.

This violation of Sofia’s right to understand her legal options and make informed choices about her future is one common example of the inhumanity and due process failures of the U.S. immigration system. An attorney with the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project (NYIFUP)— the first and largest publicly funded deportation defense program in the U.S.—helped prevent her expulsion from the United States and ultimately win asylum, but many others are not so fortunate.

I was in a cell most of the time, with no fresh air. I got to go out for recreation for an hour in the morning, and then I had to lock back in. The recreation area was like if you were in a cage like a dog. I’d go to lunch and then I was back in my cell for the rest of the day. I just sat there for months.

. . .

My lawyer expected me to be released from immigration jail in a week or two after the judge terminated the case, but they didn’t let me out. . . . There were just more excuses. I was waiting for days, and then they said they were waiting to see if the government was going to appeal. I was going crazy. My family was going crazy. I couldn’t believe they were going to have me sit and wait for an appeal. I said, ‘This can’t happen. This can’t happen.’

I called my lawyer and she said, ‘Don’t worry, I am pushing.’ She had to write to the judge and explain that ICE was refusing to let me out. I was there for close to a month longer than I should have been. Even my friends in there were talking to the guards and asking them what was going on. It was a month of calling and pressing and pressing before they let me go.

Julian, a green card holder from the Dominican Republic, was thrilled when an immigration judge ruled that he had a legal right to remain in the United States and that ICE was wrong to try to deport him. After months fighting a deportation order, a judge terminated his case, but ICE refused to release him. If it weren’t for the zealous advocacy from his publicly funded lawyer, Julian might still be imprisoned, separated from his family, and suffering in a locked cell for 20 hours a day.

Read Julian's Story (en español)

I asked for asylum at the border station in Tijuana. That is what the law tells you to do. I started to worry when border patrol put us a bus with blackened windows. When they shackled our hands and feet, I was terrified.

They put us on a plane and would not remove the shackles to let us eat or go to the bathroom. Why this humiliation? Were we going to jump out of the plane?

. . .

It could have been very bad for me when people started to get sick with coronavirus, but I had good lawyers to fight for me. When they told me I would get out, I was very nervous. I was shaking because I couldn’t believe what was happening. I was excited, but my body was shaking. Sometimes I can’t even believe that I am out, after 21 months. It feels good to see my daughter after so long. I go to church every Sunday. Because of the virus, I can only stand outside and pray, but I go.

Paul, an Igbo Christian, fled persecution for his faith in Nigeria and sought asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. He was astonished to be shackled hand and foot and flown far away to prison-like conditions in the Buffalo Federal Detention Facility in Upstate New York, where dozens of COVID-19 cases had been reported.

With the help of a publicly funded deportation defense attorney, Paul won release from detention. This may have saved his life.

In detention, we had to sleep on concrete benches or the floor because there were so many of us. I was cold and so sad to be there. Sometimes they gave us a little mattress, but there were never enough of them. They give you aluminum to wrap yourself in, but it doesn’t warm you. Sometimes, you don’t sleep.

I brought my son from Guatemala so that he could have a better life here in the United States. He was being threatened by gangs where we lived. They showed up at our house with weapons looking for him. They threatened to hurt him and kill me if he would not join. My poor nephew had been killed by one of the gangs, and so we believed their threats. . . .

When we crossed into the United States and were in the desert, we saw the headlights of the immigration cars. They asked us what we were doing, and we said that we wanted asylum. They sent us to a detention facility, which was a terrible place.

They separated me from my son after we were detained. I was in a cell with other women like me, and my son was with young kids like him. I couldn’t see him, and I was so sad and worried. It was so sad that there were so many children there, all closed in. It just fills me with sadness to remember hearing them cry.

After the traumatic terror of being detained at the border and separated from her son, Ana desperately wanted an attorney to help her fight deportation. She did not speak English, knew little of immigration law, and believed deportation was inevitable if she appeared in court alone. The Long Beach Justice Fund provided her with an attorney who guided her through the asylum application process. Since then, she has become an outspoken advocate for the campaign to expand the Long Beach Justice Funds publicly funded deportation defense program.

[My lawyer and I] spoke, and she made me feel a little [more comfortable], because I was so stressed about it. And I told her, ‘I have a long fight . . . to try to make it home to my family. Now I gotta deal with this, and I have a long fight ahead of me.’ And she was like, ‘You don’t have to fight. We have to fight and try to make sure you make it back to your family.’ When she told me that, it was a good feeling, like somebody else is caring and wanted to see you make it home. They understood the immigration law, which I knew nothing about. And was willing to fight and help me out to get home to my family.

Omari was a child when his family fled the Liberian Civil War. He grew up in the United States, built a life here, and had a family of his own. When he became ensnared in the immigration enforcement system, he feared being sent to a country he barely remembered, and being separated from his 13-year-old son. With the help of a NYIFUP attorney, he successfully made a case for bond, was released from detention, and was able to open his own business.

It has been tough, but wonderful. By the grace of God, I didn’t let that setback destroy my life. I am healthy, and I am working. . . . Whatever life hits you with, pick yourself up . . . just keep moving forward.

Julio left the Dominican Republic at the age of eight and believes he would have been deported to a country he barely knew had he not qualified for legal aid from NYIFUP. In 2015, a racist stop and frisk police encounter for “walking suspiciously” landed him in prison—and then immigration detention, which he described as even worse than prison.

ICE kept telling me that I was not welcome in the United States, and I should leave. Every so often, they would put me in a room and tell me to just sign the deportation papers. Many people in detention did not have lawyers. When they felt the pressure, they would give up, sign the papers, and be deported. Every Monday, the government would take them away, to countries all over the world—even people who had been in the United States most of their lives. I was so sad for them because we were all in the same situation.

. . .

About a week after I got out of detention, I started to feel like myself again. After about 20 days, [my attorney] brought me my green card, and I was so grateful. I saw so many people give up because they didn’t have lawyers and had no hope. I wish there were more attorneys to help people like us.

Jonathan fled El Salvador as a teenager and was eligible to remain in the United States under the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act, a 1997 law passed to help tens of thousands of Central Americans who fled political instability and violence in the 1980s. Jonathan had never heard of this law and said he would have certainly been deported if a publicly funded attorney hadn’t helped him claim the designation.