Words Matter: Don’t Call People Felons, Convicts, or Inmates

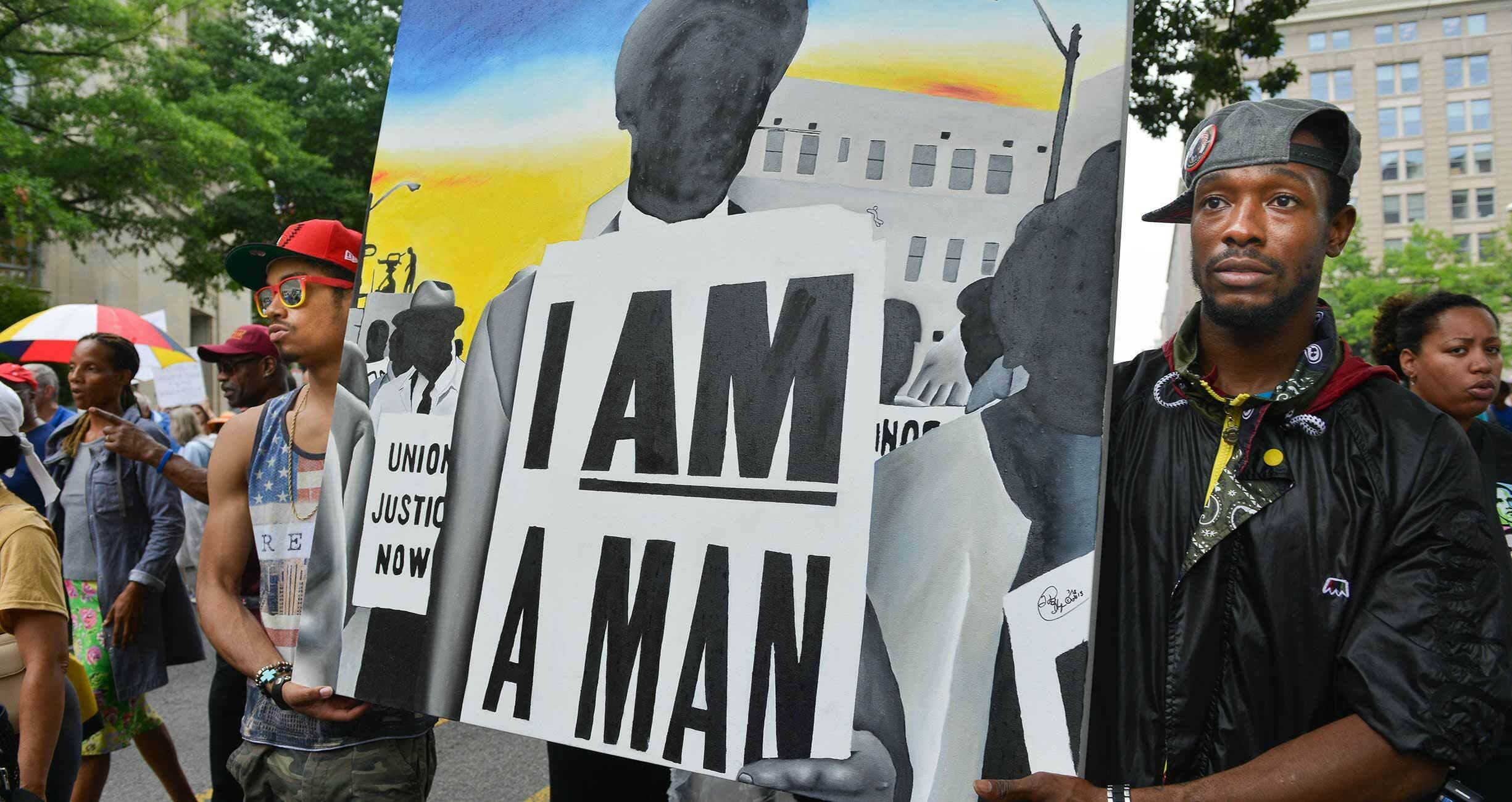

Throughout history and across the world, dehumanizing language has facilitated the systemic, inhumane treatment of groups of people. This is certainly the case for people impacted by the U.S. criminal legal and immigration systems, and that’s why it’s so important to use language that actively asserts humanity. Many people and organizations are moving away from using terms that objectify and make people’s involvement with these systems the defining feature of their identities. But many others—politicians, media outlets, and more—still use harmful and outdated language like “convict,” “inmate,” “felon,” “prisoner,” and “illegal immigrant.”

There are better alternatives—alternatives that center a person’s humanity first and foremost. These include “person who was convicted of a crime,” “person who is incarcerated,” “person convicted of a felony,” and “person seeking lawful status.” These words and phrases matter. Choosing people-first language is a step toward asserting the dignity of those entangled in these dehumanizing systems.

Instead of…

- Criminal

- Convict

- Felon

- Offender

- Prisoner

- Parolee

- Illegal immigrant

- Illegal alien

- Detainee

Use…

- Person convicted of a crime

- Person who was convicted of a felony

- Person who is on parole

- Person who is incarcerated

- Person seeking lawful status

- Person without lawful status

- Person in immigration detention

Calling a person who was convicted of a crime a “criminal,” “felon,” or “offender” defines them only by a past act and does not account for their full humanity or leave space for growth. These words also promote dangerous stereotypes and stoke fear, which stigmatize people who have been convicted of crimes and make it harder for them to thrive.

“Until this carceral state and the people of this country begin to understand the power of the words that seek to dehumanize the incarcerated or justice-impacted people, there will never be a real and substantive conversation about criminal justice reform,” said Wright. “Our humanity is maintained and respected by not referring to us in those impersonal and definitive terms, but by acknowledging our intrinsic value as human and not by defining us by the worst day or act in our lives.”

Some institutions have created policies to combat dehumanizing language. The New York City Council, for example, no longer allows city correction officers to refer to people in jails as “packages” or “bodies.” And the Biden administration recently directed U.S. Department of Homeland Security officials to stop using “alien” and “illegal alien” to refer to people without immigration documents.

But unfortunately, dehumanizing language has figured prominently in discussions over whether COVID-19 vaccines should be made available for people in prisons. More than one governor has used dehumanizing descriptions of people in prisons to explain their refusals to follow Centers for Disease Control guidelines and prioritize vaccines for people who are in congregate settings where air circulation is poor and social distancing is not possible.

Language is powerful. It shapes thoughts and attitudes, and it can have a serious effect on how a society sees and treats groups of people. People who are impacted by the criminal legal and immigration systems are too often denied their dignity. We can all work to show them respect by using language that asserts their humanity.

As Wright said, “If you can’t see me as [a] human being, then you will never treat me as a human being. And I can never escape the parameters of the system.”