Reimagining life inside America’s prisons and jails

Our criminal justice system sweeps far too many people into its net—particularly over-surveilled communities of color, as well as people who are poor or those who cope with substance use and mental health disorders. With 2.2 million people behind bars, America is an outlier in incarceration—even as crime across the country has declined precipitously. At Vera, we work to end mass incarceration and to make the system drastically smaller. At the same time, we refuse to neglect the 2.2 million people who are currently warehoused in our jails and prisons—spaces that are generally cramped and unhealthy, without natural light or fresh air.

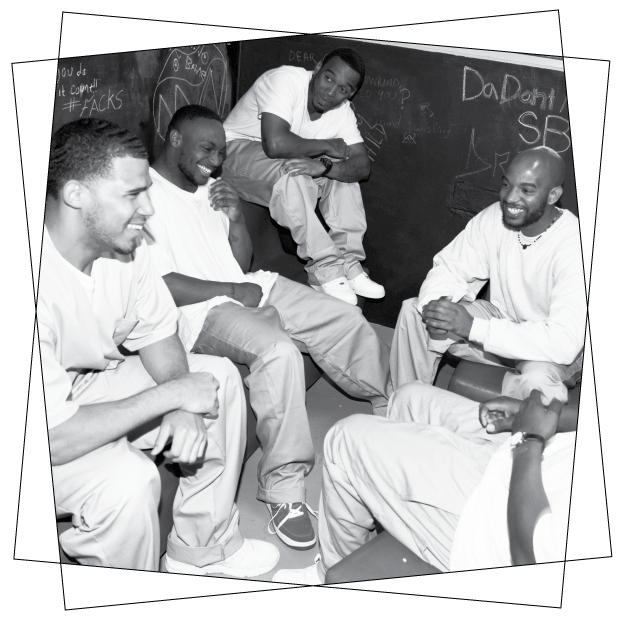

Young men of color and their families bear a disproportionate share of this burden of incarceration—a sadly predictable fact in a country where racial oppression has persisted for generations. People incarcerated in our nation’s jails and prisons rarely benefit from the education, care, and training that could help them develop and succeed. Deprived of positive human contact, they live on the edge, hypervigilant to the possibilityof violence around them and more likely to contribute to violence themselves as a result of living in such dehumanizing conditions. The result is a vicious cycle of punishment and brutality that shatters lives, devastates families, and leaves all of us less safe.

Contrast this with a typical day for an incarcerated young man living in a Restoring Promise unit. He wakes up to the ring of an alarm clock, walks out to breakfast, and is greeted by his community to start his day. He studies, meditates, or learns financial literacy on a computer in one of the many former cells that have been converted into rooms painted with the faces of President Barack Obama, Mahatma Gandhi, and Maya Angelou. He checks in with his mentor, a man serving a life sentence who lives on the unit and provides support and guidance. Later, he will play chess with a corrections officer before seeing his family. The staff in charge will stop by to let his mom know how he is doing and answer any of her questions.

As the stories of Shyquinn Dix and hundreds of others prove, it is possible to change the status quo of mass incarceration. Our Restoring Promise initiative is pioneering a groundbreaking model that prioritizes family engagement, self-expression, peer support, personal growth, education, and career readiness for young incarcerated people. This work is helping build a national movement that is fundamentally disrupting the brutal culture, design, and routines that currently define prisons and jails in the United States.

Vera is working hand-in-hand with corrections facilities in six states, red and blue, north and south, to ensure that those most impacted by the justice system—incarcerated young adults and frontline corrections staff—are supportive partners in reform. The young residents in Restoring Promise units report feeling much safer, more hopeful, and more connected to their families. Staff feel safer at work, experience fewer job-related physical and mental health issues, and find greater meaning in their work. Over the next three years, Vera plans to expand this program to a total of 10 state corrections agencies.

To build on this work, Vera is organizing international study tours of prisons in Germany and Norway—two countries at the forefront of humane corrections practices. Continuing a practice we began in 2013, these trips are bringing together thought leaders and decision makers from corrections, government, advocacy, media, and philanthropy to visit prisons and talk with European experts about ways to transform corrections and justice systems in the United States around core principles of human dignity. Past trips have proved transformative to participants, and our goal is to create a movement of leaders committed to building and supporting corrections units across the country based on the Restoring Promise model and to engaging new allies in support of this work. Vera is also amplifying the voices of young people living in Restoring Promise units by telling their stories in traditional and social media. Vera’s goal is nothing less than the transformation of American prisons and the realization of a hopeful vision of what American justice could—and should—look like.

“Not only has the T.R.U.E. program given me dignity, ... it has given me a future as a college athlete, a brother, a dad, justice reformer, and a role model. But this is just the beginning. . . .I never imagined that by being incarcerated, I would find my freedom. With truth,respect, and understanding, together we can elevate each other to greatness.”

–Shyquinn Dix

Unlocking potential: Postsecondary education for people behind bars

What? College counts in prison. Powerful stories like Aminah Elster’s (see page 17) demonstrate what Vera’s research has definitively shown: expanding access to college in prison prepares incarcerated people to get good jobs and be successful when they’re released. We know that more than 90 percent of incarcerated people will eventually come home to their communities and that education is one of the best tools to help them succeed over the long term. Pell Grants are federal financial aid grants for low-income students. Over the last two years, Vera’s leadership and support have helped our partners in the U.S. Department of Education’s Second Chance Pell program successfully enroll 11,000 incarcerated students across 27 states in college classes each year—and more than a thousand of those students have already graduated with a degree or credential.

Why? We’re making important progress, but we will not be satisfied until the opportunity to take college classes in prison is much more widely available. Our research shows that removing the federal ban on Pell Grants for people in prison would, on average, increase employment among formerly incarcerated students and boost combined earnings among all formerly incarcerated people by $45.3 million in the first year of release. This is why we launched Unlocking Potential—a national campaign dedicated to the full and permanent reinstatement of Pell Grant availability to all incarcerated people by 2020.

How? As part of our campaign, more than 80 corrections leaders, college administrators, and formerly incarcerated students joined Vera staff on Capitol Hill in July to educate congressional leaders about the benefits of postsecondary education in prison. Members of our delegation met with 104 congressional offices, and members of Congress personally attended 36 of those meetings. Over the next two years, Vera will educate key congressional committees responsible for oversight of the Higher Education Act reauthorization bill, through which the Pell Grant ban could be lifted. And we will continue to use our communications channels to press for systemic change.

On the state level, Vera is working to overturn barriers to college in prison in Michigan, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, and Tennessee. We successfully secured a total $5.7 million per year in financial aid for incarcerated students in these states. And in each state, we have partnered with local leaders on the ground—including colleges teaching in prisons, corrections departments, reentry advocacy groups, formerly incarcerated students, and others—to inform and support their work to expand access to state financial aid for incarcerated students. As with Vera’s efforts on Capitol Hill, we are working to spread the word about the value of states expanding access to college in prison in influential local media outlets and on social media channels.

“My experience with postsecondary education in prison definitely had an impact on my life. It opened my mind and eyes to the greater world around me and challenged me to want a better life outside of prison. It connects to what I’m doing now in that I was able to secure a job with relative ease when I was released from prison, as well as being quali ed to apply and get accepted into UC Berkeley within a year of being home.”

—Aminah Elster, formerly incarcerated student who earned an associate’s degree and was accepted to the University of California, Berkeley within a year of being release